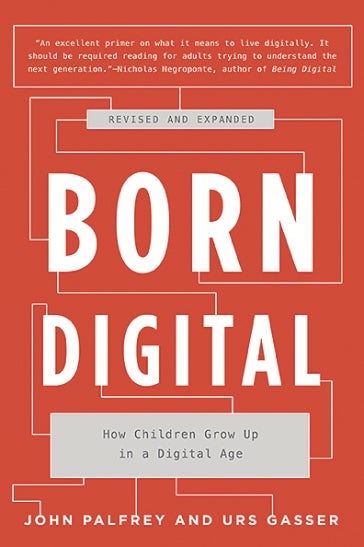

Earlier this year, John Palfrey ’01, head of school at Phillips Academy and co-director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, and Urs Gasser LL.M. ’03, Harvard Law School professor of practice and executive director of the Berkman Klein Center, published “Born Digital: How Children Grow Up in a Digital Age,” an expansion of their celebrated 2008 book “Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives.”

The writing and research that led to the first edition grew as a collaboration across continents, when Gasser was teaching at the faculty of law of the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland and Palfrey was a professor at HLS, vice dean for library and information resources, and headed the then Berkman Center for Internet & Society.

“From the beginning, the book aimed to integrate and learn from the existing scholarship on how young people were growing up and interacting in the digital age,” explained Palfrey. “It was about learning from what others had done, as there is no one field that has the lock on how young people grow up ‘digital,’ and we sought out interdisciplinary teams who approached the issue from different perspectives.”

The new edition builds upon recent research conducted by the Berkman Klein Center’s Youth and Media project and includes insights from the Berkman Klein-UNICEF Digitally Connected network, as well as many other collaborators and colleagues from around the globe.

Though Palfrey and Gasser have often joked that their book “will be obsolete the moment it is published,” they emphasize that it is critical to study how the digital age is shaping society from the ground up, beginning with the children, teenagers, and young adults who know no other paradigm. In both editions, they were driven to answer the question: How do we assure the benefits and advantages of the digital age and minimize the negative externalities? This, they acknowledged, is no easy feat—to which individuals across the generational spectrum can attest.

“The biggest takeaway is that there is a sense of shared responsibility,” Gasser observed. “In a world filled with troubling events and phenomena, the question of how we can build a better world for young people using this technology we call the internet, is one that unites.”

This fall, Palfrey, Gasser, and their research team discussed the book and the issues it explores at forums at Harvard Law School and Phillips Academy, Andover.

At Philips Academy, during an interactive session, students brought up questions related to the challenges and joys of living in the digital age. “What do we do when we tweet or snap? How is it affecting our tolerance for boredom?” inquired one student. Students shared that the internet is, for them, at once a catalyst for learning, creative ideation, and exploration, and simultaneously an environment rife with the potential for mindless distraction and lower pursuits. The conversation highlighted students’ difficulty in navigating a complex digital environment in which sharing personal information serves as the currency that binds participants in the ecosystem, while that same currency threatens their privacy in unexpected and troublesome ways.

“There has been a fundamental shift in how our world operates,” Gasser noted. “And it is one in which the distinction between the public and the private, especially in the world of social media, is increasingly blurred. Different types of semi-public and private spaces have emerged, and the challenge now centers on navigating these hybrid, complex environments.”

According to Gasser, adults who did not grow up in the age of the internet still divide the online and offline, while many young people do not. Young people, Gasser suggested, keenly experience the complex entanglement of these environments, which include personal and professional spaces, and now even physical spaces, influenced by technological innovations such as the Internet of Things and the ecosystem of its ubiquitous connected devices.

At a Harvard Law School event, Leah Plunkett ’06, associate professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law and fellow at the Berkman Klein Center, explored this same blurring of lines between the private and the public domains, with an eye to the role of institutions. She highlighted the recent incident in Ohio where police posted an uncensored photo to Facebook showing a young child in the backseat of a car, with his grandmother and her boyfriend unconscious in the front seats due to opioid overdoses.

“What is, or what should be, the definition of how the state, local, and federal government treats its citizens?” Plunkett asked. “When the state interacts with young people in digital spaces, or uses digital tools to enact its core functions, such as public health and welfare, education, or the best interest of the child, what is it doing or what should it be doing?”

The Berkman Klein Center and its collaborators continuously strive to answer these normative questions. And ultimately, according to Gasser: “Technology allows you to be playful, joyful, and do fun stuff. The same skills used for gaming and surfing can be applied within the educational context, as well as to the growing digital economy.” Whether the actors are students, parents, researchers, or the state, Gasser suggests, learning to navigate the complex hybrid spaces created by technology is key to maximizing the fruits of the digital age.

For more information, follow the Youth and Media project at the Berkman Klein Center on Twitter, the Berkman Klein-UNICEF Digitally Connected project, and subscribe to the Student Privacy, Equity, and Digital Literacy Newsletter, a collaboration between Data & Society and the Berkman Klein Center.