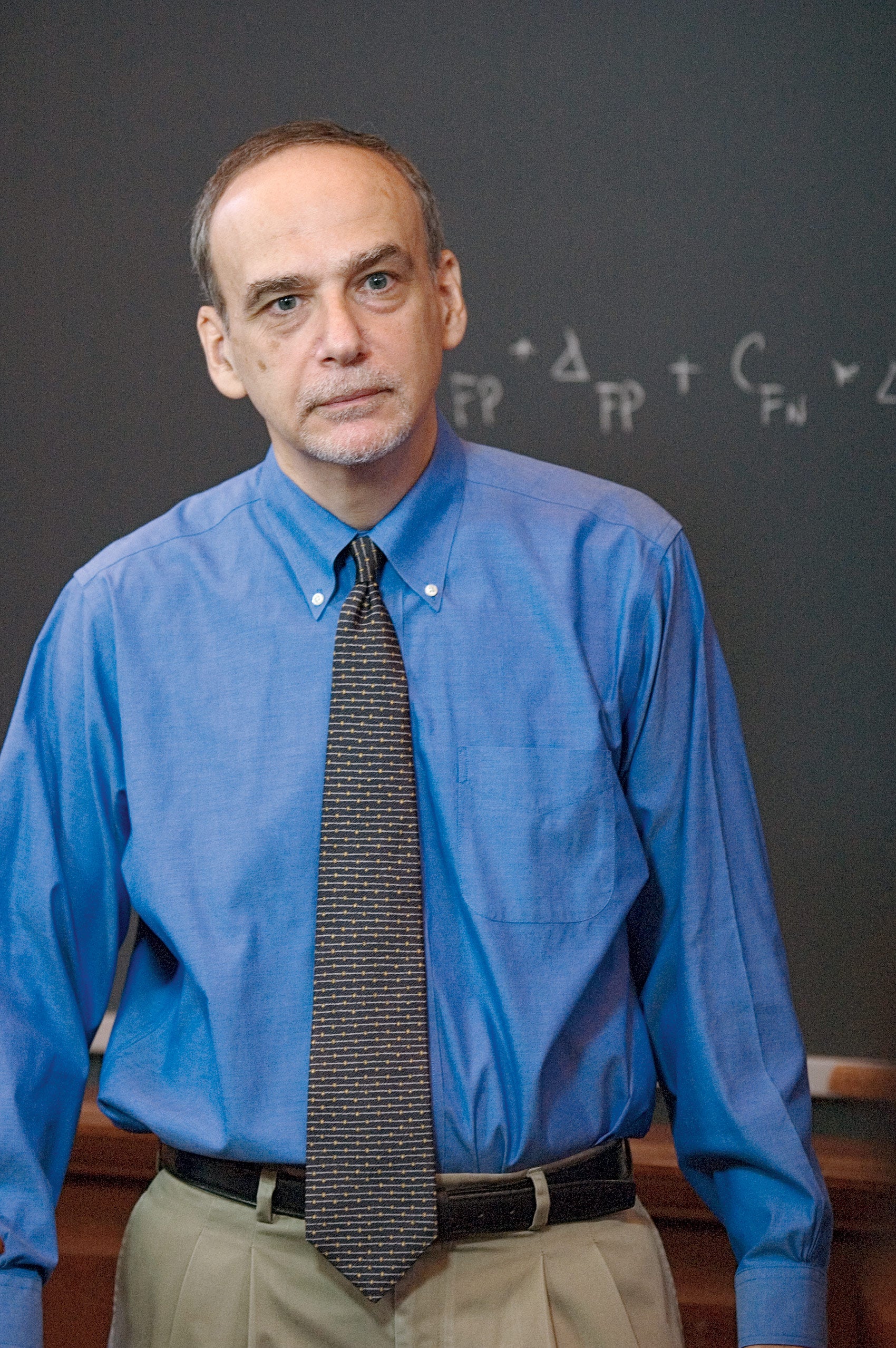

Earlier this week, Gerald L. Neuman, co-director of the Human Rights Program (HRP), and the J. Sinclair Armstrong Professor of International, Foreign, and Comparative Law at Harvard Law School, sat down to discuss HRP’s upcoming conference, “Human Rights in a Time of Populism,” with Natalie McCauley ’19.

The conference, which is free and open to the public, takes place this Friday afternoon and Saturday on Harvard Law School’s campus.

So Professor, to start us out: What is this conference about?

Thank you for asking. We plan to discuss the current rise in populism: What are its causes? What are its effects? What implications does it have for the international human rights system? And how should the international human rights system respond?

We don’t expect the answers to these questions to be the same for every country, and that’s one of the things we’re going to be discussing.

We’ll have more than a dozen leading experts coming from as far away as The Philippines and as near as our own university. There will be specific discussion on the United States, Poland, Southeast Asia, Turkey, and Latin America, as well as cross-cutting themes.

I should clarify what I mean by populism. Political scientists offer different formulations for the notion of populism, as we’ll be discussing. The phenomenon of concern here is a kind of politics that employs an exclusionary notion of the people–the “real people,” as opposed to disfavored groups that are unworthy. Populist leaders then claim to rule on behalf of the “real people,” whose will should not be constrained.

And does this populism affect internationally protected human rights?

We plan to discuss examples of how that happens. But the easy answer is: Yes, it does. Certainly within the country, and it in cases it has implications for other countries as well. If we look internally, often populism then leads to targeting the excluded groups. But it also poses a danger to the majority. Populists deny the legitimacy of the political opposition. They often try to entrench themselves in power and undermine checks. Populism can tip over into authoritarianism.

We’re talking about examples in Poland, Duterte in the Philippines, and of course, President Trump here.

Externally, populism can take hold in countries that are very important for the support of the human rights system, and then remove the support they’ve been giving. Trump’s destructive policy of “America First” is leading to the loss of US leadership with regard to human rights. Often there is permission or mixed signals being given to countries that are human rights violators. I don’t want to overstate how far that is going currently, but it may get worse with a new Secretary of State.

Meanwhile, Brexit has weakened the European Union, which has traditionally been a major supporter of the human rights system. And that is also having an effect on countries where the EU has been influential.

Have human rights institutions contributed to the current rise of populism, in your opinion?

That’s another topic we’re going to explore. Different views are going to be taken on that. For example, we’re going to be discussing whether an overemphasis on civil and political rights and a neglect of economic and social rights is contributing to populism in the Global South. We’ll be talking about backlash against certain human rights decisions in Latin America and the Caribbean. And as a further example, populist agitation in the United Kingdom has condemned a number of human rights decisions on issues like migration, counterterrorism and prisoners’ rights, as reasons why Britain needs to take its sovereignty back from Europe.

So what can be done to counteract the current wave of populism?

Well, I could take that question in different ways. Partly it’s about what citizens can do, and that’s going to depend from country to country. But we can also ask what human rights institutions can do, and what they can do directly, or what they can do to help the citizens who are resisting populist problems.

The latter is the topic that we’re planning to discuss. Should human rights institutions directly address populism as such, or should they address the causes of populism, and the effects of populism, rather than making populism itself the focus?

From my own perspective, in the face of populist propaganda human rights institutions should bear witness to the truth, and they need to defend the people who try to speak the truth in populist countries.

“Human Rights in a Time of Populism” begins on Friday at 1:30 p.m. and extends through Saturday in the Kirkland and Ellis Classroom of Langdell Hall. For information on the speakers, and to RSVP, please visit: hrpopulism.info

For those unable to make the conference, videos of the panels will be available on Human Rights Program’s YouTube channel; a publication will also follow the conference as a resource.