In 2018, ten Harvard Law School students were selected as Cravath International Fellows. During Winter Term, they traveled to nine countries to pursue clinical placements or independent research with an international, transnational, or comparative law focus. Four of these students describe their experiences.

Niku Jafarnia ’19

Niku Jafarnia ’19 spent Winter Term in Amman, Jordan, undertaking an independent clinical with the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP). Her commitment to working with refugees and asylum seekers began in college, when she drew on her Iranian heritage and her fluency in Farsi as an intake volunteer. A semester abroad, and later a Fulbright grant, took her to Turkey, where she lived in a city with a large Iranian and Afghan LGBTI refugee community. “I started teaching them English classes and tried to support them along their journey. I essentially chose to come to law school to be a better advocate for these communities.”

At HLS, Jafarnia became deeply involved in work arising from the executive orders banning travelers from Muslim countries from entering the U.S., gathering a group of classmates to protest at Logan Airport, returning the next week to assist affected travelers and working with the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinic on its amicus briefs to the 9th Circuit and the Supreme Court. Her Winter Term clinical in Jordan afforded her an opportunity to explore the full effects of the ban, well before the people affected try to enter the U.S. For the two years before the ban, “the U.S. was taking in significantly more refugees than any other place in the world. At the end of the day, even though many more spots have opened up in other countries, it’s just not enough to make up for the decrease in U.S. spots,” she explains.

Working at IRAP allowed her to refine the client intake skills she has been building through the chance to interview clients during her time there. Additionally, drawing on her earlier experience in Turkey, she researched and drafted a memo describing the ways in which the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has failed to meet its own standards. IRAP also set up meetings for its interns with a wide range of important actors, from UNHCR and UNICEF to smaller NGOs working on the ground. “It was an amazing opportunity to get an in-depth look as to what issues refugees are facing daily—from a basic, housing-and-needs level, to a policy level in Jordan.”

Traveling to Jordan gave Jafarnia a chance to address these issues from a new comparative lens. “Each country presents a unique set of challenges for refugees,” she notes; Jordan hosts a significant number of refugees, but does not offer employment for them, and is almost entirely landlocked, which makes it more difficult for refugees to leave.

“My hope for the future is to start my own organization, giving refugees legal assistance but also empowering refugees with legal backgrounds to be doing this work themselves,” she explains. “I think countries have to work significantly harder at giving refugees work opportunities. Once you let people in, they need to be given the opportunity to create a life for themselves. There’s an image of people who have been displaced as burdens on the system, when in fact they’re not given the opportunity to be self-sustaining.” Her Winter Term work in Jordan has confirmed for her that this is a change that has to happen very soon.

Filippo Raso ’18

Filippo A. Raso ’18, a Canadian national, spent Winter Term in Ottawa, working with the Privacy and Data Protection Directorate (PDPD), a government branch within the Department of Innovation, Science and Economic Development responsible for enacting, monitoring and reviewing Canada’s private sector privacy laws. His independent clinical was an opportunity to pursue his deep interest in privacy, a subject he has explored through courses, HLS clinics, and summer work, including his 2L summer in the Privacy and Cybersecurity Group at Hogan Lovells, the firm he will join after graduation. “As often happens when you start digging into something, you find out how complex and amazing it is,” he observes. “Privacy is closely related to data, and data is what’s fueling the modern economy, so it’s very exciting.”

His Winter Term project also offered a chance to work in a government setting and to gain some experience at home. “As I understood it growing up, Canada has always had this amalgam of U.S. and European influence, and its policy often lands somewhere between these two. I had learned about U.S. and European laws and approaches to privacy, and I was curious about how my home country approached it, knowing that there would be significant influences from both.”

One of the laws he looked at — the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) — provided some insight into how Canada has addressed this contentious and polarizing issue. “PIPEDA’s origin story is, in my view, uniquely Canadian,” he explains; “it’s one of compromise and consensus.” The Canadian Standards Association, a group responsible for setting national standards, created a set of voluntary principles governing the use of personal information by convening the relevant stakeholders, including industry and civil rights organizations. Despite some dissatisfaction, they achieved consensus. Five years later, the Canadian government incorporated the principles directly into law.

One of the Directorate’s mandates is to look at changes in privacy law internationally, so Raso spent some of his time examining the General Data Protection Regulation enacted by the European Union, a project that entailed an extensive, and especially methodical, literature search and review. He found the comparison instructive. “U.S. law has a strong concept of privacy. My understanding is that European law differs; they also have privacy laws, with data protection as an independent concept,” he explains. “What happens to data even if it is no longer literally private? What are the rights of individuals in controlling what happens to data about them?”

His Winter Term project left him feeling “almost like a kid in a candy shop,” Raso observes, “because the PDPD was handling [so many] issues and discussing the policy implications of the things that my friends and I banter about and that we talk about in class. The difference is that the government is the decision-maker; the PDPD’s work informs the position of the Canadian government on issues that are being actively discussed in Canada and internationally. It was exciting to see the locus of what I consider the most important issues that are affecting society today. These are the issues that I think about in my spare time.”

James Toomey ’19

James Toomey ’19 traveled to Zurich, Switzerland to conduct independent research on the regulation of biological and genetic technologies under the Swiss constitution. His project drew on a longstanding interest in the intersection of bioethics and the law, a subject that he explored in depth when he took a class on reproductive technology and genetics and a workshop on health law and biotechnology with Professor Glenn Cohen ’03.

Two articles of the current Swiss constitution Toomey explains, regulate genetic and reproductive technologies with reference to the protection of “human dignity” and, more expansively, “the dignity of living beings,” and the constitution and subsequent regulation include specific and particularly restrictive prohibitions on many kinds of reproductive technology and genetic research and medicine. “The concept is very much tied to the value of nature, and the relationship of the human species to what is naturally occurring, and that there’s an inherent moral value to human restraint in this area, to human humility,” Toomey explains. In practical terms, the provisions have a real effect on the Swiss economy (creating a restrictive regime for plant science and genetic engineering, and raising the cost of food) and on the lives of its citizens (for example, limiting access to in vitro fertilization to heterosexual married couples who can prove infertility, and creating barriers to medical research).

During his three-week trip, Toomey conducted extensive interviews with a wide range of actors, including plant scientists, law professors, advocates for animal welfare and against genetically-modified food, and government officials responsible for advising on environmental issues and assessing the safety and permissibility of gene technologies. Although the scientists, ethicists, lawyers and government officials he met were divided on the implications of these constitutional provisions, there was a consensus that dignity encompasses more than the rights and needs of adult human beings.

In addition to giving him his first exposure to a civil law regime, the project sharpened his skills in interviewing people with a wide range of opinions, “just trying to understand their views rather debating them.” He expects to do a judicial clerkship after law school, and hopes to work as a federal prosecutor; in the meantime, he’s looking forward to taking courses in bioethics during his time at HLS.

Toomey was especially interested in how Switzerland’s unique focus on the “dignity of the creature” — which conceivably encompasses all living things: animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, maybe even viruses — came to be enshrined in the Swiss constitution. Toomey senses that the concept of dignity in the context of limitations on the use of biological and genetic technologies arises from “a particular worldview about the nature of the universe and the appropriate role of humans within it,” and that although it may have arisen in Christian theology, the Swiss view dignity as a secular concept, not a religious one. Still, in the paper he is writing, he argues that the concept of dignity should be removed from the constitution. “It has chased out biotechnology research and industry from the country, dramatically increased the price of food, restrains reproductive freedom, discriminates against gay people and drives Swiss people abroad in search of healthcare,” he observes; more significantly, “it prevents people from making decisions for themselves that go to the very core of the good life. These are questions about the nature of the world and the meaning of life that no government should take a stand on.”

Alexis Wansac ’19

Alexis Wansac ’19 spent Winter Term in Germany, pursuing independent research on competency for trial standards as they relate to the prosecution of Nazi war criminals. A history and political science major in college, Wansac has explored her interest in criminal law at HLS and hopes to work in an international court. “I knew that if I wanted to work in the International Criminal Court someday I’d need more exposure to the civil law system and the inquisitorial system as opposed to a purely adversarial system,” she notes. In American criminal courts, “we go head to head, lawyer vs. lawyer, with the lawyers performing in front of a jury, and the judge as an impartial observer”; the inquisitorial system, on the other hand, “puts the judge in charge of fact-finding – with judges often questioning the lawyers and the witnesses.” Because international courts involve so many different countries, they draw on both approaches.

During an internship in Bonn during her IL summer, “I just became fascinated with German culture and German people, knowing that I’d love to someday return,” she recalls. Then, a few months later, she read a newspaper article about a 96-year-old former SS medic at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp who was deemed unfit to stand trial due to his dementia. “It got me really interested and quite frankly a little bit inflamed,” she recalls. “How is it that these Nazi war criminals, who are in their late nineties or even 100 years old, are assessed? And how, under the inquisitorial system, does a judge with so much discretion affect the process?”

In Germany, Wansac met with the head of the Central Office of the State Justice Administration for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes, a task force charged with searching for the perpetrators of crimes committed during the Second World War, and with a judge who recommended the prosecution of several war criminals, including John Demjanjuk, a notorious guard at the Treblinka extermination camp who was deported from the U.S. in 2009 to stand trial in Germany, over heavy objections related to his frail health.

Her preliminary conclusion is that the process for assessing competency doesn’t function all that differently in Germany than it does in the U.S. Like in the U.S., competency is assessed before, during, and after a trial, with the German system focusing on competency at three stages: “competency for interrogation, competency for trial, and competency to serve a prison sentence, with a defendant’s competency able to change at any time,” she explained. The German system is, however, notable in taking the defendants’ health issues into account; Demjanjuk, for example, was deemed competent to stand trial, though his participation in court was limited to two 45-minute sessions per day.

“In addition to learning about the competency standards, what also really struck me was how intricate the process was for getting someone extradited, and how important it is for countries to work together in that process – especially when you have defendants who have frequently changed their identities and are many years removed from the crimes that they are being prosecuted for,” she notes. The Central Office, she learned, will only be active for about another seven years, as many of the potential defendants will be over 100 years old at that point, and often presumed deceased. In her paper, she expects to also write about the “symbolic justice” behind these prosecutions, especially for Germany as a country — a means of asserting that “what happened before can never happen again, and people will always be held accountable.”

The Cravath International Fellowships were created in 2007 by a group of partners and HLS alumni at Cravath, Swaine & Moore, led by Sam Butler ’54 and the late Robert Joffe ’67.

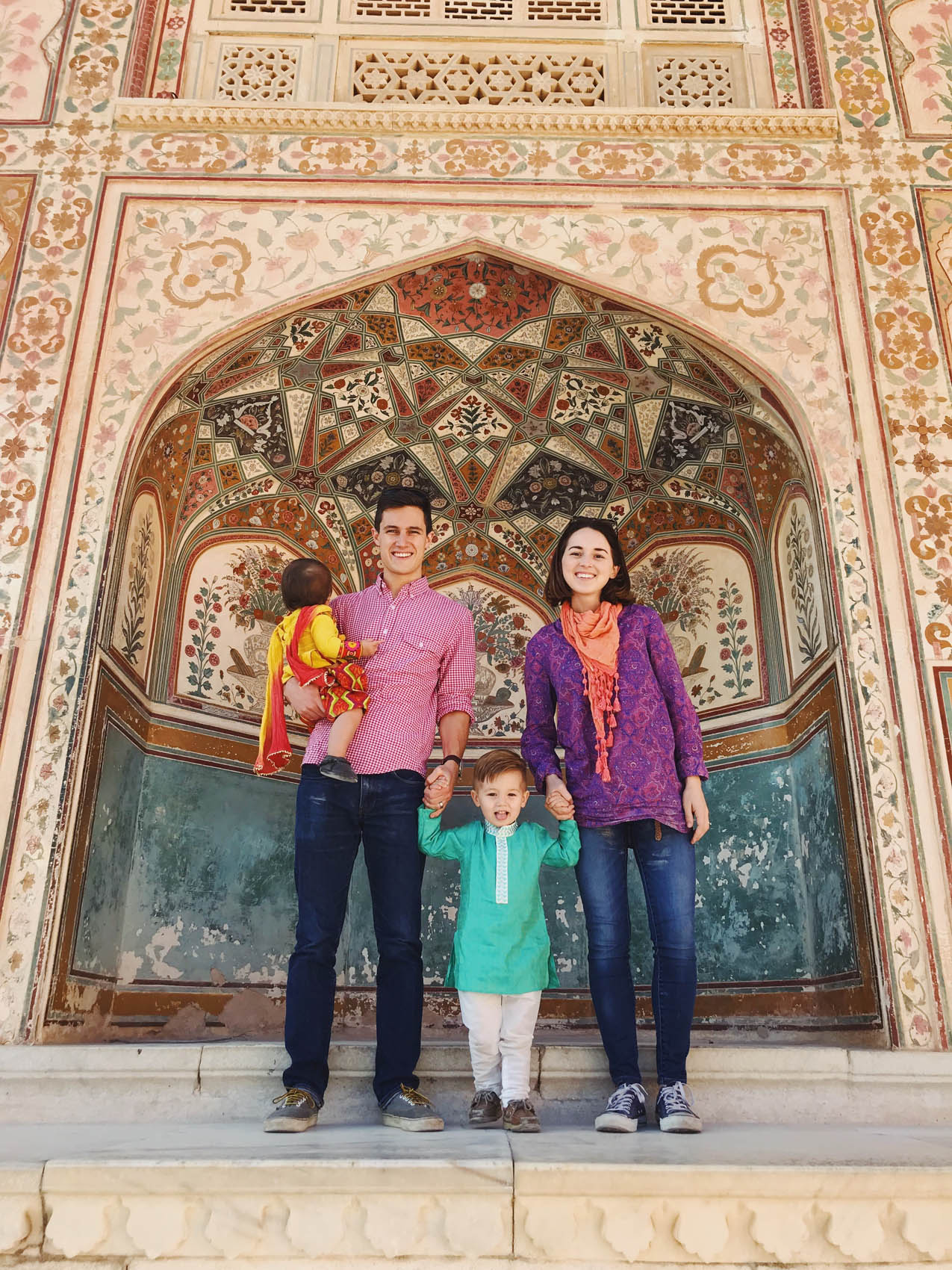

Gallery: Snapshots from Abroad

Students share photos from their travels.

During the 2018 Winter Term, 58 HLS students traveled to 29 countries conducting research for writing projects or undertaking independent clinicals, with support from the Winter Term International Travel Grant Program, which includes the Cravath International Fellowships, the Lee and Li Foundation Grants, the Reginald F. Lewis Internships, the Mead Cross Cultural Stipends, the Andrew B. Steinberg Scholarships, and the Human Rights Program Grants.