Cite by cite, download by download, the HLS corporate governance group has built a powerful reputation among scholars and practitioners, in classrooms, courtrooms, and boardrooms, for its prolific output of influential work. 2014 was the third time in a little more than a decade that half or more of the “Ten Best Corporate and Securities Articles” of the year (Corporate Practice Commentator) were written by HLS professors. Studies by corporate governance faculty have attracted about ten thousand citations on SSRN (Social Science Research Network); at the end of 2014, 13 HLS faculty made SSRN’s 100 most-cited law professors list—with Lucian Bebchuk ranking first. One of the most widely read law websites is the school’s Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation.

We checked in with several corporate law faculty during the summer for an update on what they are thinking and writing about now, and to ask what motivates their choice of research topics.

***

The Too-Big-To-Fail Problem

Mark Roe ’75 , David Berg Professor of Law

In 2010, the global financial crisis waning, Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke talked about the dangers of huge conglomerates going under and said, “If the crisis has a single lesson, it is that the too-big-to-fail problem must be solved.”

Five years later, the problem isn’t solved, but where do things stand now? Mark Roe, who has written multiple papers and op-eds relating to the crisis, in the Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal, recently applied corporate governance mechanisms “to understand how too-big-to-fail firms will wind up,” in his article “Structural Corporate Degradation Due to Too-Big-To-Fail Finance” (University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 2014).

Roe’s article won the 2015 European Corporate Governance Institute’s Allen & Overy Law Prize for best corporate governance paper; it was also voted one of 2014’s “Ten Best” in the poll of corporate and securities law professors conducted by Corporate Practice Commentator (as was his co-written article in the Virginia Law Review on the foundations of bankruptcy priority). In it he details how inefficient financial conglomerates have been shielded from restructuring pressures thanks to the “too-big-to-fail funding boost”: the lower debt-financing rates from lenders confident that the U.S. government won’t risk having corporate giants go under. This boost undercuts firms’ natural tendency to spin off businesses that no longer fit, since spunoff or restructured firms would lose that embedded subsidy. “Many normal processes of corporate governance that keep too-big-to-fails moving forward efficiently can start to degrade,” explains Roe, making the financial system overall more vulnerable.

The consensus is that regulation has improved, he says. To the extent it has, the funding boost should diminish accordingly. Then deal-financing interest rates will no longer exceed debt-servicing rates, “and the largest financial firms will face strong pressures to resize and restructure.”

Roe testified before Congress on “The Bankruptcy Code and Financial Institution Insolvencies”—a subject on which he has written several law review articles and op-eds since the financial crisis. An article underway examines and updates 100 years of bankruptcy history. “Normally, a handful of decision-making mechanisms are available to decide how and whether to restructure bankrupt firms,” he says. The dominant mechanism has shifted over the last century, often in response to market conditions, with the big three having been an administrative system imposed by a judge or regulatory agency, arising during the 1930s; a deal among creditors of a firm, dominating in the 1970s and 1980s; and the sale of the intact firm in recent decades.

Also on Roe’s agenda: a chapter in the forthcoming “Oxford Handbook of Corporate Governance.” Here he returns to his 30-year interest in how big-picture political currents and interest groups affect the structure of corporate and financial law—a topic he developed in two books and a dozen law review articles.

***

A Matter of Securities

Allen Ferrell ’95, Harvey Greenfield Professor of Securities Law

The financial crisis has generated a huge amount of securities litigation, and for Allen Ferrell, related legal issues have been of particular interest. He has covered many, applying law and economics analysis to the credit crisis, the housing market downturn, and subprime mortgage lending, among other things.

Now he has a paper coming out in the Washington University Law Review (written with Stanford Law School colleague Andrew Roper) on the Supreme Court’s June 2014 decision in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. (aka Halliburton II). The decision holds that big institutions may be able to defeat class certification in securities fraud cases if the defense can show that the alleged misrepresentations had no impact on the stock price.

“Our paper addresses the intersection of law and economics in this case,” Ferrell notes. “As economists, we’re asking: What economic evidence would speak to the showing or lack of showing of existence of a price impact?”

Ferrell is continuing research and analysis started in “Socially Responsible Firms,” a paper that won the 2014 Moskowitz Prize for outstanding quantitative research. He and co-authors Hao Liang and Luc Renneboog use large-scale data sets for 59 countries on firm-level engagement and compliance with environmental, labor, and social issues.

Using the econometrics method of instrumental variables, they test the “agency view” that corporate social responsibility, or CSR, directs managers toward “doing good with other people’s money,” wasting corporate resources and weakening internal governance. In fact, the authors find that better-managed firms engage in more CSR. “That’s because firms getting high valuations tend to be well run generally and therefore are on top of climate impact, employee protections,” and other CSR issues, Ferrell explains, whereas when a company “is a mess in terms of its internal systems, it’s not on top of things in other areas either.”

***

Mom, Apple Pie and Long-Term Shareholder Value

Jesse M. Fried ’92, Dane Professor of Law

The common denominator for two recently published articles by Jesse Fried is a unique and increasingly important feature of U.S. public corporations—they buy and sell $500 billion to $1 trillion of their own shares annually, via stock repurchases and equity issuances. “Firms on average are trading about 30 percent of their market capitalization over a five- to six-year period,” Fried explains. Yet the firms aren’t required to provide detailed, timely reports of these transactions—only monthly or quarterly aggregate data “that is not disclosed until five or six months later.”

“Insider Trading via the Corporation” (University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 2014), featured on the 2014 “Ten Best” list, focuses on an important implication of this unfettered “new world” of trading: Management teams can use corporation transactions indirectly to benefit from inside information, at the expense of public investors as a whole. “If the CEO wants to buy $1 million in shares on his own account, he has to report and it is public within two days,” Fried explains. However, “if she owns 5 percent of the company and the company buys back $20 million in shares at a low price, it is economically equivalent to buying $1 million in shares personally, except that nobody will ever see this transaction. We will see only the total amount of shares repurchased by the firm that month, and will see this only several months later.” Hong Kong and countries including the U.K. and Japan require disclosure of these transactions within a day or two, a practice Fried thinks the United States should adopt.

In “The Uneasy Case for Favoring Long-Term Shareholders” (Yale Law Journal, 2015), Fried challenges the popular view that managers who serve long-term over short-term shareholders’ interests will generate more economic value for the firm. “Like Mom and apple pie, long-term shareholder value is supposed to be good by definition,” Fried says. But here, too, transacting corporations complicate the picture: “If a company is buying and selling a lot of its own shares, catering to long-term shareholders may well lead managers to destroy economic value to get the long-term stock price up.” For example, managers may manipulate the stock price down when the firm is repurchasing shares or pump the stock price up when it is issuing shares. Evidence suggests these manipulations happen, Fried says.

***

A Director at Work on Many Fronts

Lucian Bebchuk LL.M. ’80 S.J.D. ’84, William J. Friedman and Alicia Townsend Friedman Professor of Law, Economics, and Finance

Lucian Bebchuk, director of HLS’s Program on Corporate Governance, is working on several fronts at once, including writing and research projects on how long-term value creation would be best facilitated, hedge fund activism, empirical corporate governance, and corporate political spending.

From proxy battles to liquidating assets, the influence that hedge funds have remains a contentious topic. In “The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism” (Columbia Law Review), published this June, Bebchuk and co-authors Alon Brav and Wei Jiang examine whether such activist interventions ultimately hurt or help companies and their shareholders. Analyzing data across a “five-year window,” the authors find that it does not support concerns that activism has adverse effects in the long term and that such concerns do not provide a valid basis “for limiting the rights, powers, and involvement of shareholders.” The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Economist, and many other media outlets have reported on the article’s findings and their implications for the policy debate.

How governance provisions affect share value is another issue Bebchuk has taken up in several studies. In earlier work, he and HLS faculty colleagues Alma Cohen and Allen Ferrell set forth a comprehensive “Entrenchment Index” based on key provisions that correlate negatively with shareholder value, including golden parachutes, poison pills and staggered boards. As of this summer, financial economists have deployed the index in more than 300 papers. Bebchuk is now engaged in further empirical research on the relationship between particular governance provisions and shareholder value.

With regard to corporate political spending, Bebchuk and Robert J. Jackson Jr. ’05 were the principal drafters of a rulemaking petition, submitted by a 10-professor committee they co-chaired, that urged the SEC to adopt rules mandating that public companies disclose their political spending to investors. The petition has thus far received support from more than a million comments that have been filed with the SEC, as well as from 44 U.S. senators and many institutional investors. Bebchuk and Jackson followed up with a 2013 Georgetown Law Journal article, “Shining Light on Corporate Political Spending,” and they now have a monograph in the works on the topic, with co-author James Nelson.

***

Negotiating Corporate Governance

Guhan Subramanian J.D./M.B.A. ’98, Joseph H. Flom Professor of Law and Business, Harvard Law School; H. Douglas Weaver Professor of Business Law, Harvard Business School

“I’ve had the benefit of having a seat at the table in two very different schools,” says Guhan Subramanian. “At the law school, the agency lens and incentive design are important tools when we think about boards’ work and how managers do their jobs. On the other side of the fence, at Harvard Business School, I teach in an executive education program called Making Corporate Boards More Effective, which is for public company directors. I sit on one public company board myself, and when I look around the table, I see people who are fundamentally trying to do the best job they can.”

From this dual perspective, Subramanian offers fresh proposals on governance challenges. His article “Delaware’s Choice” (Delaware Journal of Corporate Law), which also made that 2014 “Ten Best” list, takes “a more nuanced approach” to the vigorously debated staggered board structure, in which a fraction (often one-third) of the directors are elected at a time rather than en masse.

“Corporate Governance 2.0,” published in the Harvard Business Review in March 2015, is a more practitioner-oriented extension of “Delaware’s Choice.” It is his response to the “knee-jerk reactions” to governance issues that frequently set shareholder advocates and more board-centric advocates at odds.

“We all know from the Negotiation Workshop at HLS that if you negotiate issue by issue, you’re not going to achieve value-creating trades across the issues,” Subramanian says. “Corporate Governance 2.0” is the result of a thought experiment: “What would happen if you put everything on the table, and tried to sort out a compromise package on corporate governance that we could agree, overall, is a better regime than what we currently have?”

Over the past few months the article has been quoted favorably in The Wall Street Journal and The American Lawyer, among other places. In a recent speech at Stanford Law School, SEC Commissioner Daniel Gallagher praised Subramanian’s “potentially transformative approach to the corporate governance debate,” calling “Corporate Governance 2.0” an “antidote to the caustic trench warfare on these issues.”

***

Corporations Are Our Creations

Leo Strine, Senior Fellow of the Harvard Program on Corporate Governance; Austin Wakeman Scott Lecturer on Law

Away from the bench, the eighth chief justice of the Delaware Supreme Court and former chancellor of the Delaware Court of Chancery writes and lectures on those interests that have always animated his career: “public service focused on building an inclusive society,” he says, “combined with my professional preoccupation with the role of corporations in our society and globally.”

Of late, Leo Strine has had his eye on two landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases and what they portend for the role of corporations in society, noting, “A concern of corporate law scholars is that the federal judiciary’s understanding of the historical organization of corporations in the U.S. isn’t as sound as it could be.”

In his forthcoming article for Notre Dame Law Review, “Originalist or Original: The Difficulties of Reconciling Citizens United with Corporate Law History,” written with Nicholas Walter, Strine takes issue with Justice Antonin Scalia’s (’60) application of originalism in a concurring opinion for Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. “You can rationalize Citizens United, but not on the basis of the understood application of the First Amendment to corporations throughout U.S. history,” Strine contends. “Chief Justice Marshall’s conception of the corporation was that it is the opposite of the Lockean/Jeffersonian citizen, of the idea that we each are born with inalienable rights.” Rather, a corporation “only has the rights society gives to it.”

In the past, “company leaders would focus on stockholders, follow the rules of corporate law and leave the rest to regulators,” Strine says. Now the balance has shifted, and federal courts are receptive to granting corporate interests the right to act on society and the political process in ways that were not recognized 25 to 30 years ago. Yet when the executive branch and elected officials try to regulate corporate conduct, those actions are “put under the judicial microscope.”

Turning to his new article, “A Job Is Not a Hobby,” due out in the Journal of Corporation Law, on the high court’s decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., Strine cites the maxim of early common law, credited to Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634): “corporations have no souls.” By accommodating the religious views of the owners of Hobby Lobby, a retail operation, the Supreme Court established that minimum health care benefits of the Affordable Care Act are no longer a worker’s right but rather rely on the corporation’s “conscience to give workers their due,” leaving Congress to fill the gap, with shortfalls covered by other taxpayers.

Thus, Hobby Lobby allows a corporation, through whoever controls it, to “imbue its actions with religious ethos,” Strine argues, and constitutes “another situation where government is regulating the private sector, and the corporation is able to exempt itself.” He connects the Court’s decision to America’s legacy of corporate paternalism and employer efforts to restrict employees’ freedoms.

Corporations “are our creation,” he says. “These recent cases have potential to reduce the creator’s capacity to regulate the conduct of its creation. This is an important issue in a globalizing economy, challenging every notion on how to constrain corporate behavior.”

***

Commercial Entities Weren’t Built in a Day

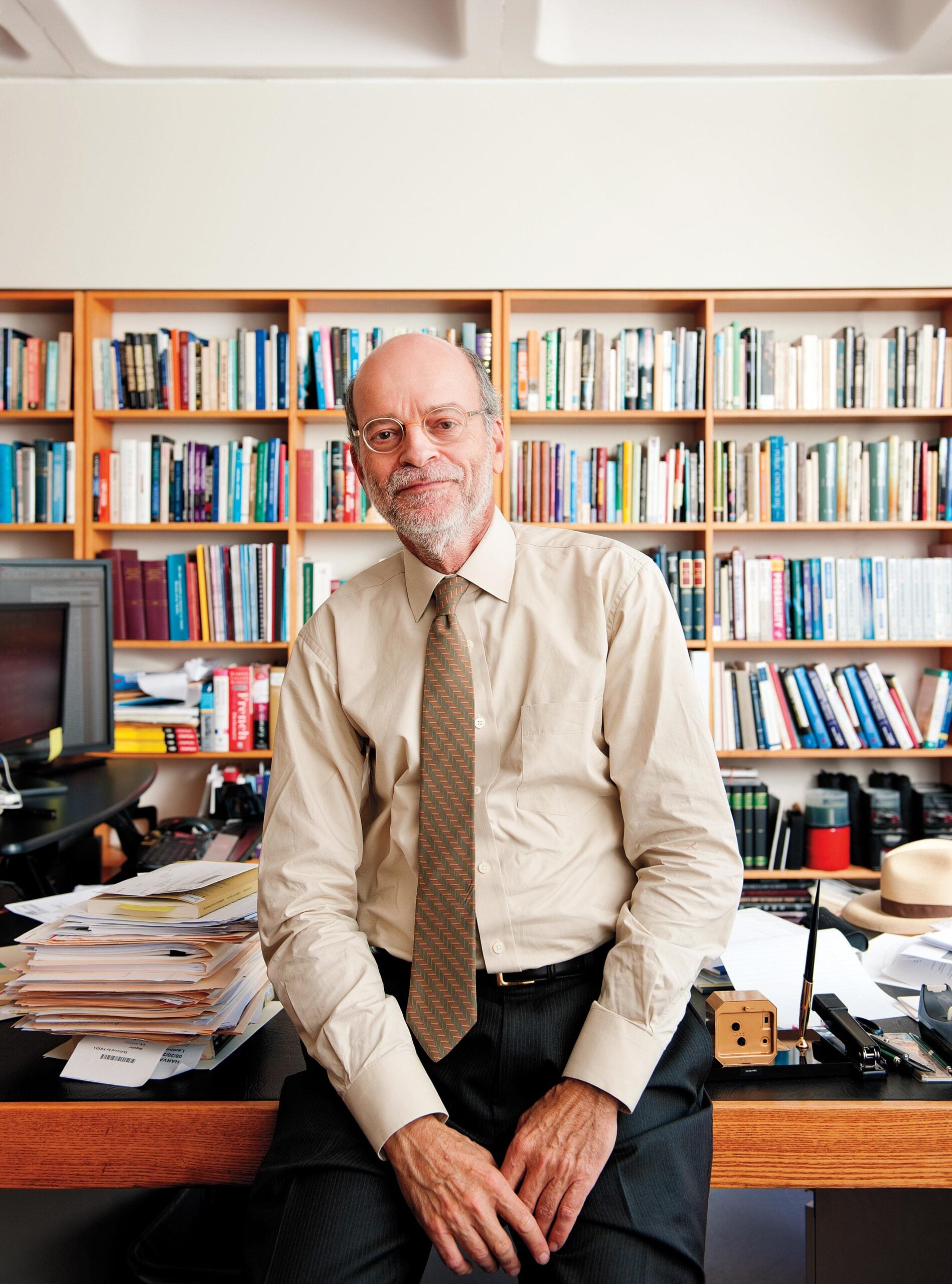

Reinier Kraakman, Ezra Ripley Thayer Professor of Law

One advantage of a large law school like HLS is its “deep bench of active business-law scholars,” says Reinier Kraakman. “Although our work and backgrounds are very different, we share general interests as well as a commitment to empiricism and meet often to discuss early drafts of each other’s projects.”

Kraakman spanned two millennia in his own research for two 2014 working papers. In “Incomplete Organizations: Legal Entities and Asset Partitioning in Roman Commerce,” he and his co-authors apply “asset partitioning” theory to explore differences between modern and ancient legal entities, “and especially how sharply business assets were separated from personal assets when creditors made claims on business enterprises in ancient Rome.” Roman laws apparently could accommodate highly utilitarian entities such as the societas publicanorum—akin to a limited partnership but available only for specialized purposes. But such niche forms lacked the legal powers required to support large enterprises.

“The most robust Roman entity was arguably the extended family whose assets were formally owned by its paterfamilias or patriarch,” Kraakman explains. “Rome relied on the estates of wealthy aristocratic families for much of its commerce, even if the nobles of these estates would engage in commerce only through slaves and subordinates.” The authors conjecture that Rome failed to create true legal entities for general use in part because its aristocracy had contempt for commercial activities, although in later centuries the imperial state’s distrust of large private enterprises also discouraged legal innovation.

Shifting to the present, in “Market Efficiency after the Financial Crisis: It’s Still a Matter of Information Costs,” Kraakman and his co-author argue that contrary to common opinion, the global economic crisis did not undercut the long-standing Efficient Capital Market Hypothesis that stock prices respond rapidly to new information in actively traded markets. The crisis “disproved” the ECMH only if analysts took market efficiency to mean that prices precisely mirrored the fundamental value of financial assets—“a slippery concept because fundamental value is inherently unobservable, unlike prices,” Kraakman explains. “A modest concept of market efficiency remains a reasonable working hypothesis for describing and explaining rapid price reactions to new information in markets for publicly traded stocks. Why these markets function as efficiently as they do is important,” he says, “and has continuing implications for regulatory reforms that attempt to mitigate the inevitable risks posed by new and complex financial instruments”—like the infamous collateralized debt obligations during the subprime mortgage crisis.