In June, a delegation from Harvard Law School led by Dean Martha Minow embarked on a 15-day, five-stop visit to East Asia and to the fore of fast-moving developments and challenges across the region. Professor William Alford ’77, director of the school’s East Asian Legal Studies program and a scholar who has long focused on the area, helped plan the itinerary and accompanied the dean, as did Professor J. Mark Ramseyer ’82 in Japan. Their daily schedule typically ran 16 hours, packed with events, meetings, and conversations with HLS graduates and fellows, including practitioners, academics, and national and local leaders.

In Korea, Alford and Minow met with Park Han-chul, president of the Constitutional Court, after which he told the dean he had received many, many visitors, but no one else had asked nearly as many questions as she did. That was the essence of the trip, according to Alford: open eyes, open mind and intense engagement with issues. He shared his impressions with the Bulletin.

Bulletin: Seoul was your first stop. What stood out for you?

Alford: Korea is an impressive example of an essentially peaceful transition over the last 30 years to democratically run institutions and rule of law. This once authoritarian society has changed in tremendously important and instructive ways, transforming itself from a poor rural nation to a thriving economy with a global reach. Law has played a key role, buttressing and building on political change. Korea today has a robust and vibrant civil society, with a plethora of NGOs, church groups, and think tanks—and contention and debate; it’s never dull in Korea! HLS graduates have had a hand in this in so many ways. The alumni we met with at just one event included heads of firms, jurists, business leaders and public interest advocates, as well as senior government officials.

Two other HLS grads, Kang Hee-chul LL.M. ’90 and Yun Sai-ree LL.M. ’82, are founders of Yulchon (“Law Village”), a firm of more than 300 professionals, which also performs substantial pro bono. A third, quite different example is the work of Park Won-soon, the mayor of Seoul, a city with a population of nearly 10 million. Mayor Park was a visiting scholar in the Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School in the early 1990s. When the dean and I visited him in Seoul, he pulled out a faded newspaper clipping he’d saved from his Cambridge days; it was an article about Harvard’s United Fund drive that caught his eye. Mayor Park told us that example inspired him to promote a similar model of civic charity in Seoul.

Earlier you mentioned the country’s thriving economy. What challenges in managing growth are distinct to Korea?

A powerful driver in Korea’s economy are the chaebol—conglomerates, many with large family ownership. A familiar example is Samsung. The chaebol collectively wield tremendous power. The sense of our alumni was, on the one hand, that Korea needs the chaebol to compete on the global stage, but on the other, that it also would benefit by creating more space for small and medium-sized enterprises. Doing so requires deftness—and this is where skilled lawyering is critical.

What impact do tensions on the Korean Peninsula have on our alumni there?

Some alumni said to us that they imagine it’s like living in Israel: If you thought all the time about the worst-case scenario, it would be awfully hard to carry on. Some people in public policy positions anticipate eventual reunification and are hoping to play a constructive role going forward. Justice Mok just recently helped to restart an economic zone in the southern part of North Korea, the Kaesong Industrial Complex, which had closed down during tensions in April. He took this on as a pro bono project in June, and indeed the complex reopened in September.

Forgiveness and the Law

Who has authority to forgive and in whose name? … This topic reaches well beyond law to human experience, hopes and suffering. But it is the kind of inquiry that we in law must consider as law itself must serve human purposes. The solutions that courts and legislatures direct can speak to our highest hopes for fairness, predictability, equality, and freedom from bias and corruption. But legal tools are just that: tools. The purposes they serve should be ours. Law can be a tool for harmony, for compassion and for human growth—for converting suffering into opportunity. Or so I hope.

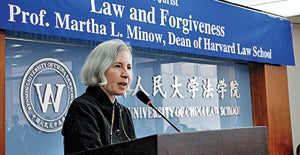

—From a talk delivered by Dean Minow at Renmin Law School in Beijing

Now to China. In Beijing, Dean Minow presented a talk at Renmin University, home to one of China’s foremost law schools. What was her topic and what was the response?

Before our trip, when Renmin Law School Dean Han Dayuan, a former visiting scholar in our East Asian Legal Studies program, invited Dean Minow to speak, she shared with him half a dozen possible topics for her talk. He picked the most ambitious on the list: “Forgiveness and the Law.”

The room where Dean Minow spoke overflowed with hundreds of undergrad and graduate law students at Renmin plus students from other Beijing law schools. The energy was palpable, especially after the talk, when students raised remarkable, probing questions, adding their own comments on pressing themes. On the role of the judiciary, one student said—and I’m paraphrasing—“You spoke about forgiveness, which suggests some departure from the strict letter of law, some discretion from the judge to administer forgiveness or accede to a victim’s wish that an assailant be forgiven. All that suggests discretion; it suggests judges who are highly professional and independent. You can’t give such leeway to just anyone; it has to be someone who has the right qualifications and temperament. Our judges are not necessarily well-positioned to exercise this level of discretion.”

Given the students’ candor, did the issue of free speech come up in the dean’s conversations with Chinese alumni?

We had lengthy, moving conversations with leading legal academics and lawyers about academic freedom and other big challenges that China faces. There was, for instance, much discussion of the current controversy over the role that the constitution is meant to play in China. Corruption was yet another topic—there was widespread agreement that it is a massive problem that must be reined in. Some steps already are being taken by China’s new leadership, though it is too early to know what sustained impact they will have.

Did you meet with anyone whose work offers particular insight on China right now?

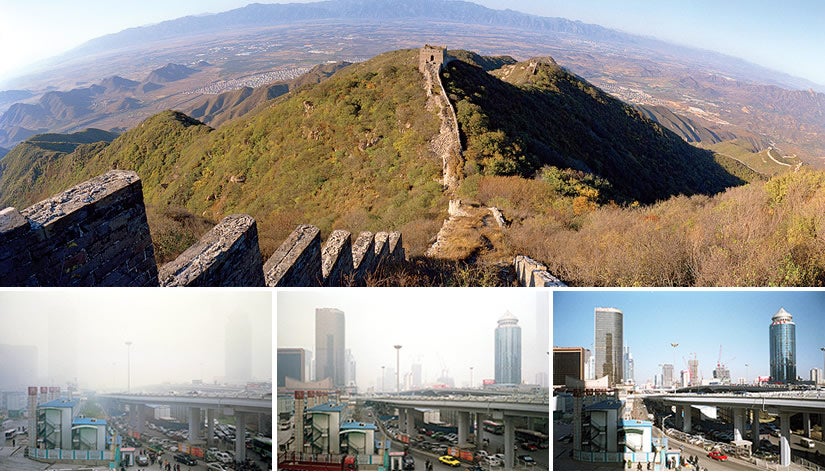

We visited the National People’s Congress and met with Xin Chunying, a two-time visiting scholar at EALS, who has vice ministerial rank and heads the NPC committee in charge of drafting laws. She described the challenges of legislative drafting in China, including soliciting public opinion when legislating for a continent-sized country whose inhabitants have a range of views. In the aftermath of profound changes, including the migration of more than 250 million people from the country to the cities, how can laws best protect the interests of all involved? Balancing tradition and family values while taking into account how much life has changed, how fluid things are and how difficult law enforcement is means China’s problems are not amenable to easy legislative solutions.

On to Taiwan, whose residents are acutely aware of rising China’s proximity. What stands out from your time there?

We had the opportunity to meet with Taiwan’s President Ma Ying-jeou S.J.D. ’81, who is also head of the Nationalist Party. The HLS Leadership Council of Asia met for the first time, in Taipei, and 20 of its members from throughout the region accompanied us. The conversation with President Ma was wide-ranging, touching on memories of his time in Cambridge but also on weightier subjects. One topic was the role of “ambiguity” in relations between Taiwan and the PRC. Dean Minow pointed out that sometimes ambiguity is what you want and even need as a lawyer. You don’t want to draw every line sharply and delineate every last point.

Later that day, we met with Annette Hsiu-lien Lu LL.M. ’78, former vice president and a leader of the opposition Democratic Progressive Party, who is now immersed in public interest work.

Taiwan Back Story

Taiwan’s current president and the former vice president, from opposing parties, overlapped at HLS: Their intertwined paths reflect the story of Taiwan’s transition to democracy. Read the story from the Summer 2006 Bulletin.

What did discussions with HLS grads focus on in Hong Kong?

Hong Kong was full of energy, whether you talked with people who were optimistic or those concerned about interaction with Beijing or those who held both views.

In addition to extraordinary Chinese alumni in Hong Kong, there’s an interesting group of expats, among them my dear friend Paul Theil J.D./M.B.A. ’81. He initiated the first foreign investment in a private insurance company in China, and subsequently also created the first Chinese commercial microfinance company, reaching out to large numbers of urban and rural microentrepreneurs to fund and spark small enterprises.

What impressions did you take away from your visit with alumni in Japan?

Alumni are very proud of Japan’s standing in the region and the world. But we also heard concern about the need to re-energize the economy after 20-plus years of economic slowdown and about how best to deal with the still unfolding impact of the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, which to some degree has shaken people’s trust in the authorities. Many, such as former HLS Visiting Professor Yukio Yanagida LL.M. ’66, expressed the hope that legal professionals will play an active role as Japan works through its challenges.

Let’s return to China. It was a major focus of the trip, given the deeply entwined futures of the U.S. and China. Any final thoughts?

Some students talked with the dean about how their world is so radically different from that of their parents, some of whom have no external sources of information, while their children are seemingly tethered to their electronic devices.

China’s great economic accomplishments—hundreds of millions have moved out of poverty—are juxtaposed with staggering environmental problems and many other profound dilemmas. One student who returns to her grandparents’ village each year told me that the pollution there—air, land, water—is massive, with horrific health consequences. In this blizzard of change, the most basic questions—about the environment, social justice, anti-corruption, gender equality, the nature of property—are being debated and tested. It’s an incredibly important, if uncertain, moment for law and lawyers.