Stepping down after 14 years as dean, Robert Clark ’72 has changed the institution with the money he raised, the faculty he nurtured and the programs he shaped. Underlying it all is an unflagging devotion to Harvard Law School.

It was the night of Robert Clark’s final performance as dean. True, he would go on to perform as dean in the usual way–leading faculty meetings, giving speeches, meeting with alumni–for a few more months. But on March 8, he strode on stage for the last time as the 800-pound gorilla at Harvard Law School. Literally. The student parody, as it had for the last 10 years, featured a certain special guest, this time in disguise. Wearing a hairy suit, the dean eventually ripped off a rubber ape mask to reveal the man behind the facade, a man who, before the curtain closed, expressed his love for the students. “We love you, Bob,” a young woman shouted back, and people applauded and at that moment seemed to understand the heft he has brought to Harvard Law School and the devotion he feels to the institution and everyone who is a part of it.

His show of unbridled affection was perhaps rare for a person more prone to reflection, whose passions are stirred by scholarship and ideas. But Robert Clark ‘ 72 can still surprise people, even after 14 years as leader of the most prominent law school in the world. From the start, he surprised some with his effectiveness at raising money for the school. He surprised others with his ability to quell faculty discontent. And, for someone dubbed a “traditionalist,” he surprised too by overseeing fundamental change to the structure of the law school in the Strategic Plan, which has already transformed the student experience and will transform the school in myriad other ways.

Credit: Charles Gauthier Robert Clark ‘ 72

“I think the school had arrived at a point where change was possible given a certain kind of leadership,” said former Harvard University President Neil Rudenstine, Clark’s boss for 10 years, “and I think Bob provided that leadership at that moment.”

Nevertheless, Clark says he never coveted the deanship. Nor did he expect to get it. But he was compelled by duty to accept it. Now, as he prepares to leave the job and, after a sabbatical, return to the school as a professor, the senior dean at Harvard University has forged a legacy at HLS that some say is just as strong and just as lasting as its most legendary deans.

According to Visiting Professor Daniel Coquillette ‘ 71, who is writing a history of HLS, Clark belongs in the company of school leaders like Story, Langdell, Pound and, most comparably, Griswold, for their long service and major contributions to the institution.

“No other dean of Harvard Law School has really made the kinds of appointments he made,” said Coquillette. “Other deans have done remarkable things, but what Clark did [is] build a foundation for the future. . . . My personal opinion is that 20 or 30 years later we’ll have a better appreciation of what he did than we do now.”

Raising money is the means, Coquillette says. But it’s what you do with the money that counts. The renovation of the Langdell library, completed in 1997, is the most visible example. But, behind the scenes, Clark also devoted money to an unprecedented number of faculty appointments, hiring 39 new tenured and tenure-track professors. In addition, the school enhanced the curriculum during his deanship to include more than 250 elective courses, added resources to existing research programs and introduced several more, including empirical legal studies, Internet and society, and Islamic legal studies. The Strategic Plan, which the faculty approved in 2000, has changed the 1L experience at HLS for the first time in decades, reducing section size and establishing cohesive “law colleges.” More is to come, based on a $400 million campaign to fund the plan, which also calls for improved infrastructure and more faculty, interdisciplinary training, financial aid, research and international initiatives.

Credit: Joe Wrinn/Harvard University News Office Former Harvard University President Derek Bok ’54 greets Robert Clark shortly after choosing him to be dean of HLS.

The changes spearheaded by Clark demonstrate his “willingness to face up to a long-standing reality about the school, and that was that a lot of students didn’t like being there,” said Derek Bok ’54, former Harvard University president, who chose Clark as dean. “They valued the education they got, but they didn’t regard it as a particularly pleasant experience. There was always a significant minority who did, but there were far too many who didn’t, and Bob was willing to take that on and was able to introduce changes in a way that seems to have made a substantial dent in that problem.” Sometimes, Clark acknowledged, he struggled to change an institution at which change happens slowly. He worked, he says, to get faculty to look at the demands of the external world, to overlook what was important merely on campus and focus on what the school should prepare its graduates for: “I felt very good about getting a planning process going that didn’t lead to people just saying, ‘Gee, the library’s run down; let’s build a new one,’ but led people to think: ‘We ought to build on our international operations because law practice and legal scholarship are going global. We ought to build on our interdisciplinary studies because that is the way the insight-producing academic trends are going. We ought to connect to the world of practice because otherwise our law school will become irrelevant.'” “The idea that you could just prepare students by instruction in a few standard subjects and that would be enough struck me as ridiculous,” he added. “We need to broaden our teaching and scholarship and realize that not everyone has to take the same path.”

Credit: Mary Lee/Harvard University News Office Clark surveys the renovation of Langdell library in 1996.

Clark understands the different paths people can take. He began his own career on the road to the priesthood, studying at seminary and later earning a Ph.D. in philosophy. He planned to teach philosophy while concentrating on social sciences, and came to the law school hoping to learn more about society and organizations. And, though at first the notion of “thinking like a lawyer” jolted him, he liked what he found–the law school as a window on understanding large organizations. He would go on to write one of the definitive legal texts on corporations.

“He was a brilliant student and a great scholar,” said Professor Emeritus Victor Brudney, Clark’s teacher and mentor at HLS. “His Corporations treatise is simply nonpareil.”

After graduation, Clark worked for two years at Boston’s Ropes & Gray before receiving an offer to teach at Yale Law School. The school granted him tenure in three years, a record at the time. But he was attracted to the qualities of Harvard Law that he still celebrates: its sense of a metropolis, not a village, a lively and engaging and unpredictable and sometimes unwieldy intellectual environment.

He became enmeshed in it quickly as an HLS professor in the ’80s, finding some students thirsting to learn business law and others on campus disapproving of teaching law and economics in any course outside of antitrust. At the same time, Clark criticized elements of the critical legal studies movement (which challenges traditional approaches to the law and emphasizes using the law to achieve social justice) and, by extension, the several HLS professors considered its leading adherents.

Such opinions may have been acceptable coming from a professor. But it was not, for some, acceptable for that professor to become dean. In public comments, several faculty members, as well as the Harvard Crimson, spoke against the appointment, calling Clark too ideological, too rigid, too polarizing to lead a faculty already rife with tension over bitter tenure debates and campus unrest.

Bok well understood the atmosphere on campus. For he had been not only a Harvard Law student, but a faculty member and dean of the law school himself. Of the many decanal appointments he made as Harvard University president, he agonized over this one like no other. But when he made his decision and the criticism followed, he did not relent or apologize. Indeed, in a way, the response showed him that Clark was precisely the person for the job.

“I really did feel that the conditions of the school were so heated and so politicized that no strong appointment could possibly escape criticism from some quarter,” said Bok. “It might have been conceivable to find someone that no one would criticize very much, probably because the individual involved was either so chameleon-like in his point of view or so lacking in any point of view that nobody would have anything to criticize. But that clearly was not the kind of dean we needed.”

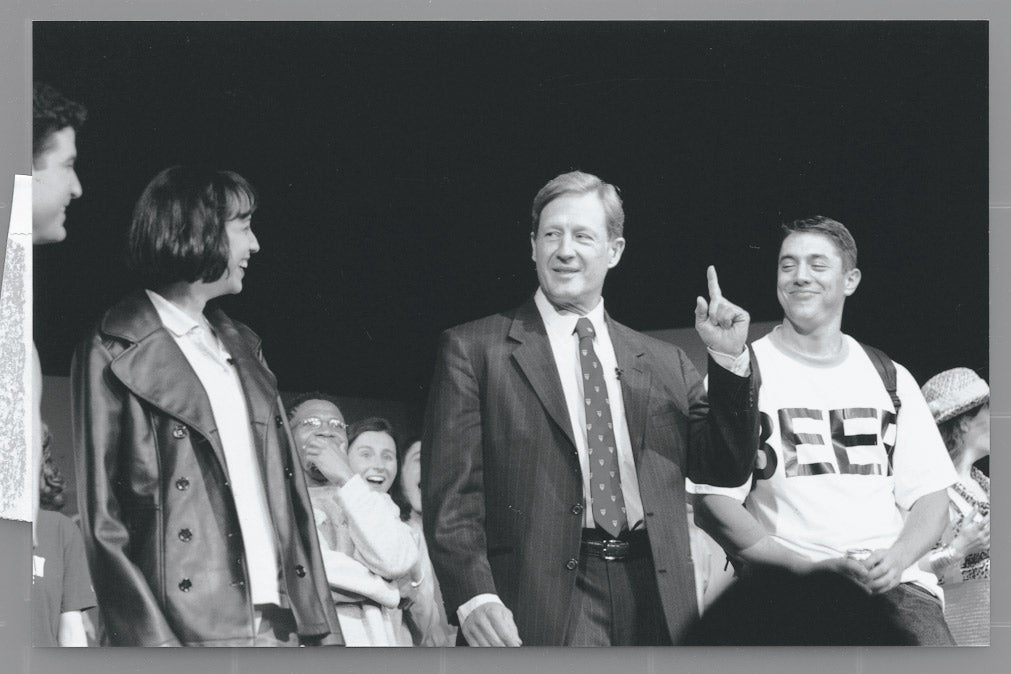

Credit: Richard Chase Clark makes a bid at the Public Interest Auction.

In addition to the initial faculty concerns, some students also voiced dismay over the appointment, complaining that Clark was too corporate-focused. And the dean does value the private sector and will not denigrate it as some want him to, he says. He contends, however, that he wants the law school to train leaders for all parts of society, and it is the pay disparity–not the law school’s influence–that leads many graduates to law firms, where they can indeed do much good for the world. “I got into trouble, I think, because I did not ever engage in a ritual critique of the private sector as part of our reasoning for giving special assistance to those contemplating the public sector,” he said. “I think that one of the reasons some people can maintain their resolve to enter or remain in the public sector–or the nonprofit world, which hosts most law teaching–despite the wretched salaries, is that they think, ‘I am doing good and the others are doing bad.’ That is what some use as a psychological tool to reinforce their socially good but hard-to-sustain choices. My view is that the second half of the argument is not right and is often counterproductive to the goal of creating good public-private relationships. Most of the value in society is created in the private sector, and even those committed to public service need to face up to that squarely and realize that, though many of our graduates are going into the private sector, they will nevertheless contribute to the advancement of overall human welfare.”

Students would later protest Clark’s decision to disband the school’s discrete public-interest advising operation (he soon reinstated it) and hold sit-ins to increase diversity on campus. But according to Lisa Ferrell ’90, who chaired a student-formed committee on the dean search, the majority of students approved the appointment, eased by Clark’s willingness to listen to them.

“I was then and continue to be a fan of Dean Clark,” said Ferrell, now an attorney in Little Rock, Ark. “He met with students. He met with our group. He met with students who were concerned. I thought he did a great deal to reach out.”

View More

“I made a vow to myself to never seek revenge against colleagues who opposed me and to forgive people for their foibles”

– Robert Clark

As a new dean, Clark also aimed to bring the faculty together. And, belying some of his critics, he aimed to do it by being respectful and understanding of every point of view. “I made a vow to myself to never seek revenge against colleagues who opposed me and to forgive people for their foibles,” he said.

He created and chaired an appointments committee, listened and persuaded and eventually saw the infighting turn to reconciliation. Professor Laurence Tribe ’66, who chaired the faculty search committee for a new dean, says Clark fostered a calmer, more productive atmosphere. “There are those who thrive on conflict who would say that that was bad and he was suppressing division, but I don’t think that he was suppressing anything,” he said. “It was pretty clear that rabble-rousing was not going to achieve very much during the time he was dean and that things were on an even keel, and for people who want to get on with their own work and want to spend time with their students on substantive matters and not be engaged by faculty politics, it was probably a welcome change.”

Clark succeeded not only by lessening conflict, said Tribe, but by showing support for faculty members’ work, both on and off campus. One professor who initially spoke against Clark’s becoming dean noted recently that he always read everything the faculty produced. He values scholars and scholarship and engaged in the intellectual life of the school, even when he was away from the school, as he frequently had to be.

For throughout his tenure he concentrated on fund-raising, traveling to alumni and other donors in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe and taking countless shuttles to New York City, among many other places, to achieve the goals he set for himself, a mental checklist of things he wanted to accomplish each year. Before he became dean, he had never raised money. And when he began, people wondered if he would be good at it, given that his personality is more oriented toward studying than schmoozing. But he was good at it, and provided an example for others, said David Leebron ‘ 79, dean of Columbia Law School since 1996.

Credit: Gustav Freedman HLS students get a lift from Clark while cleaning a vacant lot in Boston.

“If you listen to people talk about Bob Clark, one of the things people say is that he is a very thoughtful, serious person who takes ideas seriously,” he said. “That’s true about his scholarship and his position as a leader of legal education. And it’s one of the things that makes him such an effective fund-raiser. Fund-raising is not about making everybody your best friend or telling the best joke, although I’ve always found Bob to be an appealing speaker. It is about projecting and articulating the mission of an institution. When you have a conversation with Bob, or you listen to him give a talk, you get the strong feeling that this is a person of enormous integrity, who will be straightforward with you, and will be very thoughtful and balanced about whatever issue is put before him. He instills wonderful confidence about both his leadership and his school.”

Clark built rapport–and built the endowment–with alumni partly through his ability to manage the law school, to engender confidence that their money would be in good hands, says John Cogan Jr. ’52, a member of the HLS Visiting Committee and Dean’s Advisory Board. But he also built trust because he never tried to be anything he was not.

“I think what his appeal may be is what you see is what you get,” said Cogan. “Of course, he is not a grandiloquent speaker, but there is an authenticity about him. Without having hubris, he has enough confidence in his judgment that he can be strong.

“You can never forget that he is a philosopher too. He sees the role the law plays in the world. In the end, when he is looking at the law school, he is looking at it as an element of good.”

Clark left the seminary a long time ago. But some lessons stay with him, like the need to sacrifice for a greater good.

That is his prevailing strength and what separates him from so many others, says Professor Roberto Mangabeira Unger LL.M. ‘ 70 S.J.D. ‘ 76, who is associated with the critical legal studies movement.

“His fundamental task was to preserve the openness and multiply the voices, and I think he has in many respects succeeded,” he said. “And I insist the precondition of this success has not just been an administrative efficiency but a moral quality of great importance: of devotion, of self-sacrifice on behalf of an ideal of something larger than himself.”

What often goes unremarked, said Unger, is “the extraordinary stoicism and devotion of the man.” Indeed, you will not hear Clark complain about the life of a dean. In fact, he calls it “an indescribably rich and meaningful and varied experience.” But it is also never-ending and enervating. He does not regret leaving the job, and that’s clear from the robustness and speed with which he answers a question on the subject. These days, it is not a job many people do for as long as he has. And, inevitably, the job changes you, even as you work to change an institution.

Professor Charles Ogletree Jr. ‘ 78, associate dean for the Clinical Programs, has seen the changes from his days as a visiting professor in 1985. At first, he didn’t know if he wanted to accept a permanent faculty position under Dean Clark (he did, in 1993). They had, he said, mutual skepticism toward each other. “I wasn’t sure he valued the assets that I bring to the law school,” Ogletree said. But in time he saw that they shared the same values if not the same politics. They might disagree on almost any topic but could agree on the fundamental mission of the law school: to make it the best in every conceivable field.

“Bob Clark has the ability to grow and learn, and he will say he’s a very different person in 2003 than he was in 1985 and that he was a very different person in 1993 than he was in 1989,” said Ogletree. “His growth has been gradual, but I think his acceptance of a whole host of points of view has been rewarding. I think he’s expanded the faculty in important ways, in subject areas that would have not been in any way at the top of Bob Clark’s list of priorities, and yet I think he says with conviction and passion that Harvard has a strong faculty in many, many areas and that it’s the envy of the legal academy, and that is something that will be a part of his legacy as dean.”

In appreciation of that legacy, the school owes Clark a great debt of gratitude, says Tribe. But it is not likely a debt he would seek to collect. He does not tout himself or look back self-satisfied at what he has accomplished. He also does not bemoan what he could not do. The path to unhappiness, he says, is to think about what might have been. He is looking forward to his scholarship, to the world of ideas, to what he can teach and what he can learn. The most important thing he did and will still do, says Clark, is to believe in and care about the Harvard Law School.

New Dean to Begin Elena Kagan ’86, a professor at HLS and a former White House lawyer, will replace Robert Clark as dean of the law school on July 1.

Named by Harvard President Lawrence Summers in April, Kagan teaches administrative law, constitutional law and civil procedure. She recently chaired the school’s Locational Options Committee, which evaluated a possible move of the law school to Allston.

Kagan formerly served as a professor at the University of Chicago Law School. From 1995 to 1999, she served in the White House, first as associate counsel to the president and then as deputy assistant to the president for domestic policy and deputy director of the Domestic Policy Council.

She will be the first female dean in the history of Harvard Law School. More on Kagan to come in the next issue.