The third Celebration of Black Alumni drew more than 700 graduates to the school in September and filled the campus with excitement and engagement, crossing generations. The Bulletin interviewed participants who graduated during each of the past five decades. They reflect on their own experiences and the path of social change in the era of the nation’s first black president.

Peggy Cooper Davis ’68

A professor at New York University School of Law for nearly 30 years, Peggy Cooper Davis ’68 has written about professional pedagogy, feminist and critical race theory, child welfare and substantive due process. Her book “Neglected Stories: The Constitution and Family Values” argues for an anti-slavery vision of 14th Amendment rights of personal and family autonomy.

On her time at HLS: One of the reasons I’m so excited about the kinds of connections I can make now and the kind of community I see building around the Celebration of Black Alumni is of course there was none of that then. I was one of very, very few women and one of very, very few African-Americans, and one feels that. I think the school is a better place for having more perspectives, a more comfortable place to me than the Harvard Law School I entered and left. At the same time, it’s inspiring to see a kind of continuum and growth.

I also feel a special bond because my husband [Gordon Davis ’67] and I were there together and married after law school. There almost begins to feel like a tradition of Harvard Law couples. Seeing Michelle and Barack is incredibly inspiring, given all that.

Before she joined the NYU faculty, she worked in public interest law: It wasn’t until after law school, when I was working in legal services and then civil rights law, that I began to feel that I could take ownership of the law.

She also served as a family court judge: Using the law as a judge was a very sobering experience. I’m very glad that I did it before I began to teach because it was a great feeling to go into law teaching having been an advocate in a variety of contexts but also having felt the weight of responsibility for making decisions about people’s lives.

At NYU Law, she oversees the school’s experiential learning program: An important part of my teaching is bringing feminism and critical cultural studies to bear in the classroom. I stress the relational nature of practice and lawmaking, and I work to develop students’ interpersonal and social intelligence as conscientiously as I work to develop their logical and quantitative skills. My students not only think about but also confront in simulated practice settings tough issues involving identity, diversity and social justice.

On race and justice today: I feel that we’re at a point in history where social justice struggles are not technically about race, but problems are allowed to persist because of racial attitudes.

Our public education system is pretty much a disaster. I think efforts to resolve that problem are stymied because they are perceived as helping “the other,” so things we ought to do in our collective interest we often don’t do because we’re not thinking collectively but in our own self-interest or in the interest of groups.

Things have happened that I’d never dreamed would have happened in my lifetime. But I’m still stunned and frightened by the divisiveness and hatred that I see.

In summary: I still feel that I’m working counterculturally.

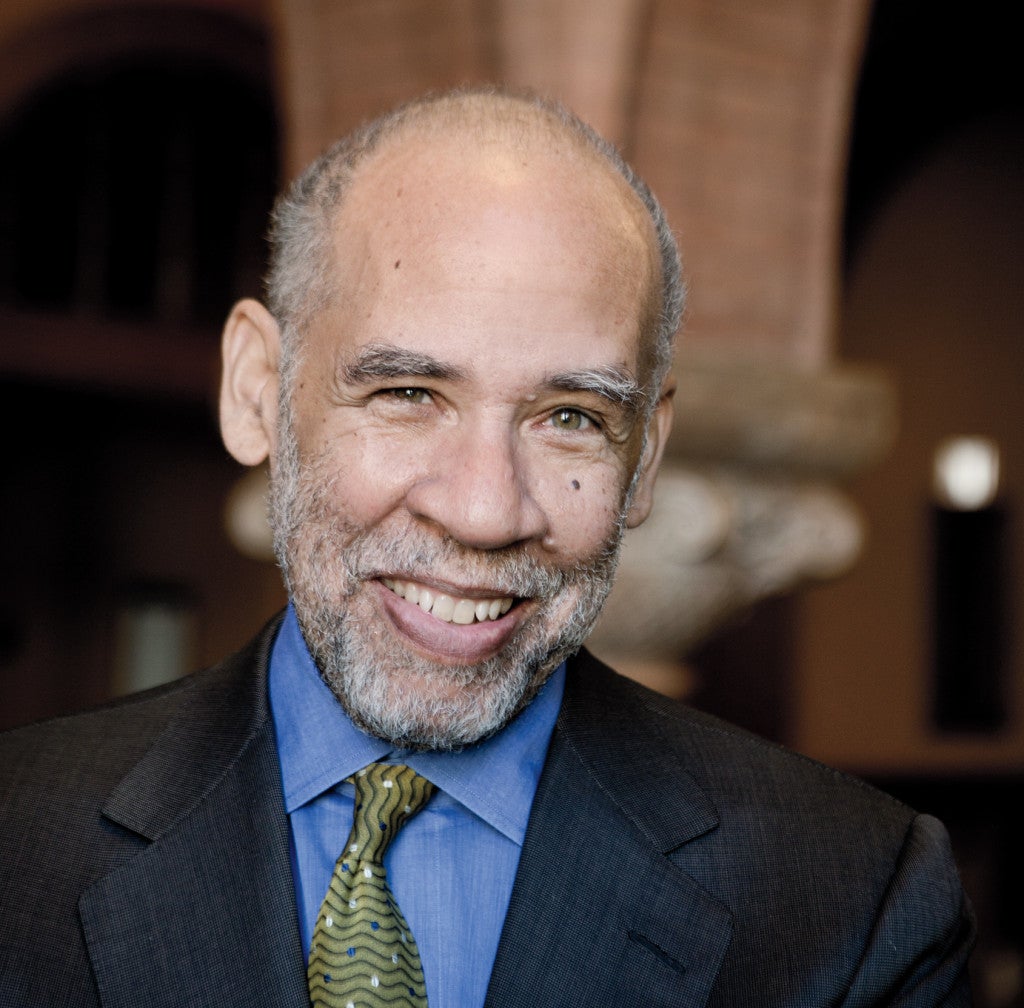

John Payton ’77

John Payton ’77 has worked on issues of social and racial justice throughout his career, as a partner at Wilmer, Cutler, Pickering, Hale and Dorr and now as president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

The social movements of his youth sparked his passion for civil rights: Most of the people who grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, certainly who were African-Americans, were greatly affected by social justice, racial justice issues, the civil rights movement, and wanted to figure out how we could make a difference in our society. I concluded—and I think a lot of people who went to law school with me concluded—that if you really wanted to be a change agent for social justice, being a lawyer was probably the best platform to have.

He successfully argued before the Supreme Court that the University of Michigan could consider race to attain a diverse student body: It’s had the effect of changing some parts of the conversation. Diversity has essentially been embraced by all of corporate America. It’s now commonplace to hear people across partisan divides say they, too, want to make sure they are inclusive and are diverse. I think that’s something that is quite healthy for our democracy.

Race-based measures are still needed to address injustice: All minorities, all women, have seen great progress. That said, we still have very serious issues that relate to race. There are all sorts of studies out there that are not disputed that [say] bias and implicit bias still are in very high numbers.

On the Obama election: It’s great success that comes after great sacrifice by a lot of folks.

… and postelection: I have to say I did not expect the level of unbelievable hostility that his election would spark. I know we have divisive politics, but the extra layer of “He’s a black man poisoning our civic culture” caught me off guard. It’s there. It’s not going to go away. It’s a reflection of what remains to be done.

He was drawn by the history of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund: Everyone knows Brown but there are cases leading up to Brown and way past Brown. It’s a tremendous legacy to be able to look back at that and then to be the head of the law firm that Charles Hamilton Houston [LL.B. ’22 S.J.D. ’23] and Thurgood Marshall created that changed this country dramatically for the better.

Sadly we still have a lot of work to do. There are still issues in education and economic justice and certainly criminal justice, where we have mass incarceration as a horrendous problem, and voting rights is always under challenge.

What we can do now: No matter what you do in your career, you can still do things that help advance issues of social justice and racial justice. That includes pro bono, which is now in every crevice of our profession. You can obviously financially support things. But there are also things you can do outside of your job, becoming involved in your communities in ways that matter, becoming involved in how your school system works and striving to make it better, making sure that our civic culture is healthy. It’s not necessarily being a lawyer but being a good citizen. I think those broader responsibilities are what is going to make us a better society, and I think all of us have some commitment to that.

Loretta Lynch ’84

Loretta Lynch ’84 has found rewards in different aspects of legal practice, from law firm partner to her current position as U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York.

She served on the trial team for the Abner Louima civil rights case, overseeing the prosecution of the New York City police officers charged with sexually assaulting Louima, a Haitian immigrant: It was a very tense atmosphere. It was extremely racially and politically charged at the time. My way of dealing with high-profile cases like that is to completely separate from the press. What you have to do is insulate yourself.

Lynch also served as special counsel to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, for which she conducted a special investigation into allegations of witness tampering and false testimony: People are traumatized. The only thing that’s similar to it is the trauma some people still feel after 9/11 in this country. There are certain things that never leave you. When you’re talking with a survivor, particularly someone who physically survived an attack, and they tell you about hiding in a pile of dead bodies all night long because they knew if they moved, the genocidaires who were waiting to see if anyone was alive would come back and finish the job. You think, How does the human spirit deal with that?

What I say to young lawyers in particular is, I wish for them to have the kind of experience [I did], to use the law in a way that’s transforming. I think you can do it in any venue because every case is important to the people involved in it. It doesn’t have to be a genocide case.

Some critics have said that the criminal justice system harms the African-American community: There were people who, until I worked on the Louima case, thought, Why do you do this? To me, I do it because I think everyone deserves protection.

Frankly, it shouldn’t be an easy thing to stand up and say this person by their actions has forfeited their right to walk among free people.

She has conducted outreach with Muslim-American groups who have spoken about facing bias: What I hear them saying is what so many African-Americans said in the ’50s and ’60s: “We’re part of America, too. We’re just like you.” I think every group struggles with that.

On whether she has faced race-related bias herself: You mean when I was a young associate when I went to take a deposition and everyone assumed I was the court reporter. Or when I interviewed at a law firm and the receptionist looked at me and said: “You can’t be Loretta Lynch. She goes to Harvard.” I think everyone has those stories.

Most African-Americans are very cognizant of assimilating into mainstream culture, but you’re also very aware of and very comfortable with your own culture. To me, that’s an advantage. I think it makes you flexible; it makes you see things from more than one perspective. I look at people who have only one experience, and I think that’s really unfortunate. That’s where those comments come from. In their worldview, this is how they see black people. I learned a long time ago, I can’t really change your worldview. You can get to know me, you can spend time with me, and if your worldview changes as a result of that, fine. But it’s really not my job to try to change it.

Timothy Wilkins ’93

A graduate of HLS and Harvard Business School, Timothy Wilkins ’93 conducts business deals with corporations around the globe as a partner with Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in New York.

His brother, HLS Professor David Wilkins ’80, established the Celebration of Black Alumni: It was important to both David and me because both our father and his brother are also alumni of Harvard Law School. For us, the idea of the tradition and bringing together African-Americans from all the different generations at the law school was especially poignant.

He is his firm’s first and only African-American partner in the United States: The challenges continue to be real for lawyers of color. The numbers when we were first coming out of law school were quite stark. I did not know more than two or three black people who had become partners.

A member of Freshfields’ global diversity committee, he has sought to increase the number and improve the experience of minority attorneys: It’s the personal mentoring and support that can make or break the successful trajectory of an African-American lawyer so that they believe that the firm’s culture is supportive of them, and they also have as many opportunities to succeed and be involved in the most exciting work. Being creative around how to think about diversity from a recruitment point of view but also from an inclusion point of view will continue to be an important challenge for large corporate law firms.

He embraces the role of mentor: Lawyers are most successful if they can cross borders and work with people from different offices and different cultures. If we are struggling with successfully handling difference and cultural variety in our own firm, that’s going to make it harder for us to be successful with our clients.

On practicing in Freshfields’ Tokyo office: It was a really dynamic and exciting time because you got to do international transactions shoulder to shoulder with your Japanese bengoshi (Japanese-qualified lawyers). We saw the quality go up substantially for international clients as well as Japanese clients doing deals overseas where you could have both lawyers’ approaches to the law coming together to come up with joint solutions.

Negotiating styles can differ between cultures, he says: My experience in Asia is that it often takes an important few sessions of understanding the big-picture issues and the ultimate goals of the client before people get down into the detail and the small points. And I see sometimes U.S. lawyers jumping immediately to the clause on Page 23, Subpart B before they’ve really given the clients the chance to understand the bigger picture and also the relationship between the two parties.

The impact he can have as partner: I do find that the privilege of actually being at the table at the partners’ conference, at the global diversity committee meeting, means that I have an obligation to speak out and make sure that our firm is carrying out its role and responsibilities to the highest degree that it can, but also that the firm is making the most positive impact that it can.

Darin Johnson ’00

As attorney-adviser in the U.S. Department of State, Darin Johnson ’00 advises the Bureau of International Organization Affairs on United Nations-related legal issues.

As a commissioned officer in the Army, he was an attorney in the Secretary of the Army, Office of the General Counsel Honors Program at the Pentagon: I come from a long line of military service. It’s very much a part of our family tradition.

In Baghdad in 2007, he advised the U.S. ambassador to Iraq and other senior State Department officials: It was right around the time when the insurgency had become very active. It made for a very tense environment. It also offered the opportunity to deal with some really interesting, cutting-edge, critical issues.

As a member of the Black Law Students Association at HLS, he helped organize an African summit, for which students visited law schools in African countries, including South Africa: There’s a certain level of respect and admiration [in South Africa] for the African-American community in the United States. In speaking with students about the transition from apartheid, and the freedom movement of South Africa, I saw a lot of inspiration drawn from the civil rights movement. There are a lot of parallels.

On those who have come before him: One of the powerful things about coming back for the Celebration [is] actually getting to spend time with alumni who have been at the law school in different periods and hearing about their experiences generally as well as during their time at the law school. For those of us who are younger, we really have an appreciation for how far society has come and how far we’ve come as African-American students and alumni.

On the struggles that remain: You name the problem, you’ll see a disproportionate impact in the African-American community. So while our community has come very far, we also have a lot of ongoing challenges that still need to be confronted.

He moderated a Celebration panel on “International Law and Foreign Affairs: Adding Our Voices to the Global Dialogue”: I very much appreciate efforts at inclusion, expansion, protection of minority rights. That appreciation of the civil rights struggle of African-Americans and the community that I’ve come from definitely has led to a greater sensitivity to the same struggles that may exist for minority communities in other countries.

***

HLS Bestows Awards

During the Celebration of Black Alumni, HLS Professor Annette Gordon-Reed ’84 (left) received the HLSA Award, and Walter Leonard (middle), former assistant director of admissions at HLS and former president of Fisk University, and Derek Bok ’54 (right), former president of Harvard University were awarded the HLS Medal of Freedom.