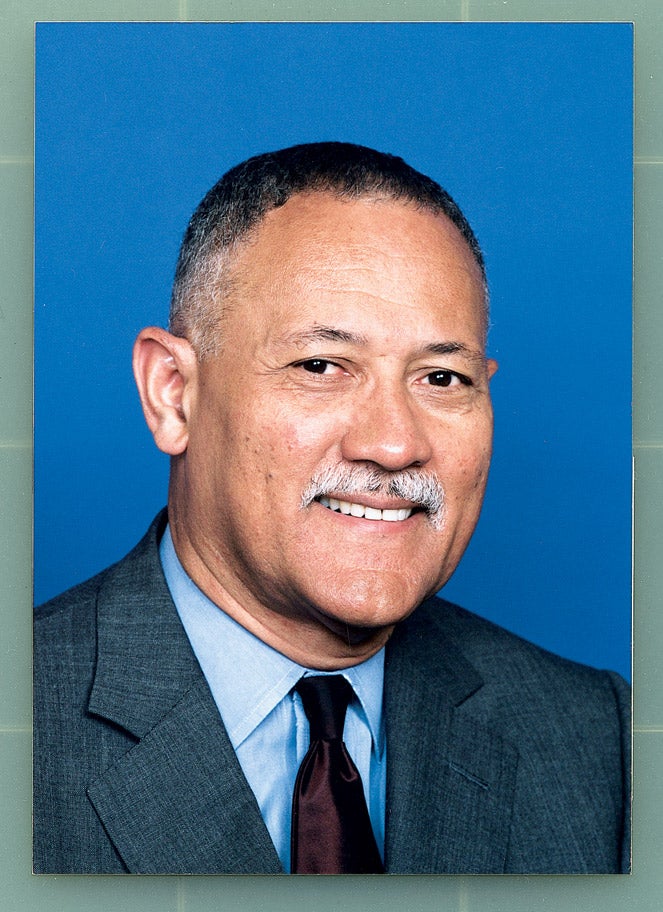

It took Weldon Rougeau ’72 only 90 seconds to get himself expelled from college.

Holding a sign demanding integrated lunch counters and more black workers, Rougeau walked into a Baton Rouge department store in 1961. His protest got him arrested and jailed for three weeks. A second arrest for distributing “don’t buy” leaflets landed him in solitary confinement for 58 days.

Eleanor Roosevelt praised Rougeau’s “willingness to sacrifice himself.” Southern University kicked him out for good.

That setback didn’t slow down his civil rights work a bit. He switched to registering African-American voters in Louisiana and Florida and went on to work with Vernon Jordan at the Voter Education Project and the United Negro College Fund. In between, he found time to finish college at Loyola University in Chicago, attend Harvard Law School, and practice law for a year back home in Louisiana.

But a legal career didn’t hold him for long. Instead, he’s hopped from the public to the private sector. He served as a legislative aide to Louisiana Senator J. Bennett Johnston and as chief of staff to HLS classmate Congressman William Jefferson, and he enforced affirmative action laws in President Carter’s Labor Department. He also worked as a vice president at American Express and Loyola University Health System, and headed a Chicago job-training program.

“I’m attracted by management challenges,” said Rougeau. Since childhood, he says he’s also been driven by a desire to improve the lives of African-Americans. Growing up in rural southwestern Louisiana, Rougeau used segregated public bathrooms and remembers the slights his sharecropper parents suffered.

“A fire was lit in me, and I wanted to do more than just accept it,” Rougeau said. That’s why, he says, he picketed the department store. And, he adds, it helps explain why he took on his latest management challenge this spring. He returned to Washington as chief of the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation (CBCF).

Founded in 1976, the CBCF is a nonpartisan policy, research, and educational institute. Rougeau says his goal is to make the CBCF the premier center for policy research in areas of interest to the African-American community, such as AIDS, housing, and education. “So many of the issues have taken on a 21st-century bent but are still rooted in the effect of legal segregation,” he said.

One top priority is increasing the homeownership rate among African-Americans. The goal, Rougeau says, is to add another million homeowners within the next five years and encourage recent college graduates to start thinking about buying a home.

Though separate from the Congressional Black Caucus and barred from political advocacy, the CBCF still gives Rougeau a chance to work again alongside politicians. Many African-American members of Congress serve on its board, including its chairman, Congressman Jefferson.

In his first weeks, Rougeau planned a trip for members of Congress to Princeville, N.C., the first town founded by former slaves, which was devastated by floods in 1999.

“I love politics,” he said. “I love political decision making. I love being around politicians. In this job, it’s a skill I can turn to.”

Rougeau flirted with the idea of running for Congress in Louisiana himself but has cast aside that ambition: “I stayed away from home, and now I think I’m a little too old for that.”

Even after decades up north in Washington and Chicago, Rougeau continues to have strong ties to the southern Louisiana African-American Catholic community in which much of his family still lives, says his son, Vincent Rougeau ’88. “The family home is always Louisiana,” Vincent said.

For while Rougeau has traveled far, he’ll always remember where he came from.