Since Harvard Law School first admitted women in 1950, the school has progressed toward gender parity in admissions, with the Class of 2017 the first to be 50 percent female.

Yet among HLS graduates who work at law firms, men are significantly more likely to be equity partners and to be in positions of leadership than their female classmates—even though women work more hours, on average. Women experience significantly more workplace consequences, including loss of seniority, as a result of having a child, and twice as many female partners as male partners do not have children. The percentage of male law partners who are married far outpaces the percentage of female partners.

These are among the provocative findings of the first systematic empirical study of the career trajectories of HLS graduates, conducted by the HLS Center on the Legal Profession. Begun with a grant from a group of HLS alumnae, the study examined data collected in 2009-2010 from four HLS classes and was released this year as “The Women and Men of Harvard Law School: Preliminary Results from the HLS Career Study.”

Women, even those who achieve prestigious positions, are leaving the legal profession “in alarming numbers,” the study found.

“These findings are especially important because they underscore that even women who have all of the same educational credentials as their male peers continue to experience important differences in career outcomes, particularly in obtaining leadership positions in private law firms,” says David B. Wilkins ’80, vice dean for global initiatives on the legal profession and faculty director of the center, who co-wrote the study with Bryon Fong, the center’s assistant research director, and Ronit Dinovitzer, associate professor of sociology at the University of Toronto.

Even as the legal profession stands at a pivotal point of transformation, the status of women in the law presents its own complexities. The number of women entering the legal field has increased dramatically—with women in leadership positions at many major legal institutions, including three female justices on the U.S. Supreme Court—but the percentage of women in top positions lags far behind that of men. And women, even those who achieve prestigious positions, are leaving the legal profession “in alarming numbers,” the study found.

There wasn’t a large gender gap in pay between HLS men and women in their first jobs out of law school, probably because over 60 percent worked for law firms, where there are standardized salaries, according to the study. But there are significant income differences between men and women in their current jobs, with the gap narrowest for the Class of 1985 and largest for the 1995 cohort. The biggest factor appears to be that men who aren’t practicing law are more likely than women to work in business, where their total compensation is far in excess of that of even highly paid law firm peers, it found.

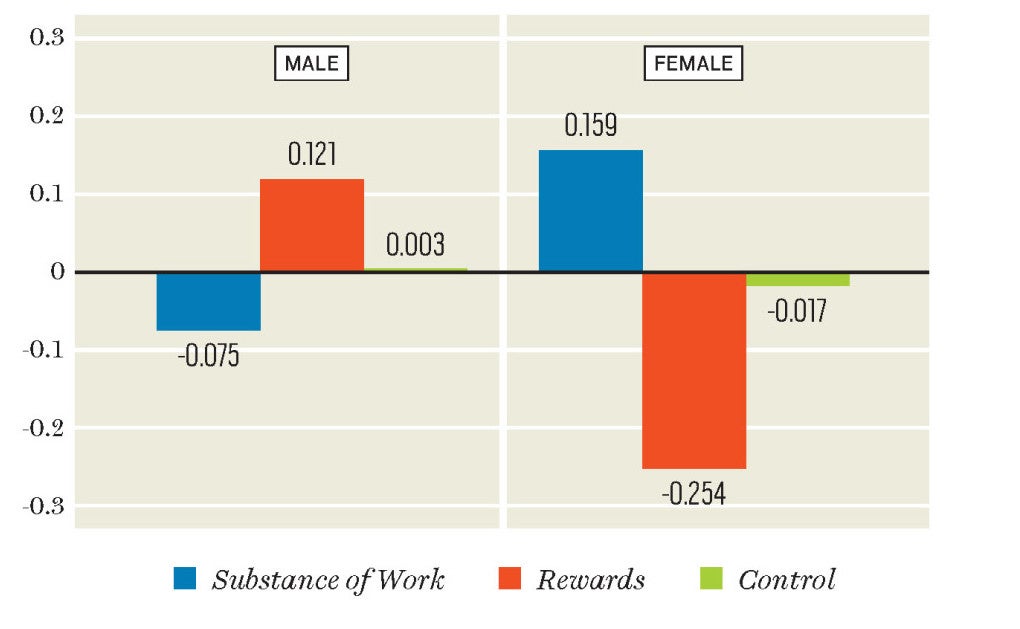

Factors of Satisfaction–Across Employment Sectors

Even as women enter the legal profession in increasing numbers, “the typical career path in the profession is not just made for a man—it is made for a man who has a wife who does not work,” Wilkins says. “These patterns of work, organization, and advancement will have to change significantly in the coming years if the legal profession is to continue to attract and retain the quantity and quality of talented lawyers that clients and society will need to tackle the complex legal problems of the 21st century.”

Both women and men report extremely high levels of satisfaction with their decision to attend law school and with their overall careers. But men report being more satisfied with the rewards—that is, money—while women are satisfied with the substance of their work. Neither women nor men report being particularly satisfied with the control they have over their work and personal lives.

Among other findings:

Students with work experience between college and law school have increasingly become the norm at HLS.

→ Just over one-third of HLS graduates enter public-sector positions in their first jobs, with women slightly more represented in this sector than men.

→ Women and men entering the public sector have higher grades in law school than those joining law firms.

→ Across all cohorts, women are significantly more likely to be working part time or not to be in the paid workforce.

→ About a quarter of women and men working full time in their current jobs do not practice law.

→ Men make higher grades as 1Ls, but that gap largely disappears with respect to cumulative grades.

The study examined the careers of HLS graduates across the past six decades, through surveys of four classes: 1975 (one of the first classes in which women made up a significant percentage), 1985, 1995 and 2000. To establish a baseline for comparison, it collected data from the 1950s and ’60s and it used data from admissions records and transcripts, which was anonymized and reported only in the aggregate. It also compared findings from “After the JD,” an American Bar Foundation-sponsored longitudinal study co-written by Wilkins, which has been tracking the professional lives of more than 5,000 lawyers, including graduates of many law schools.