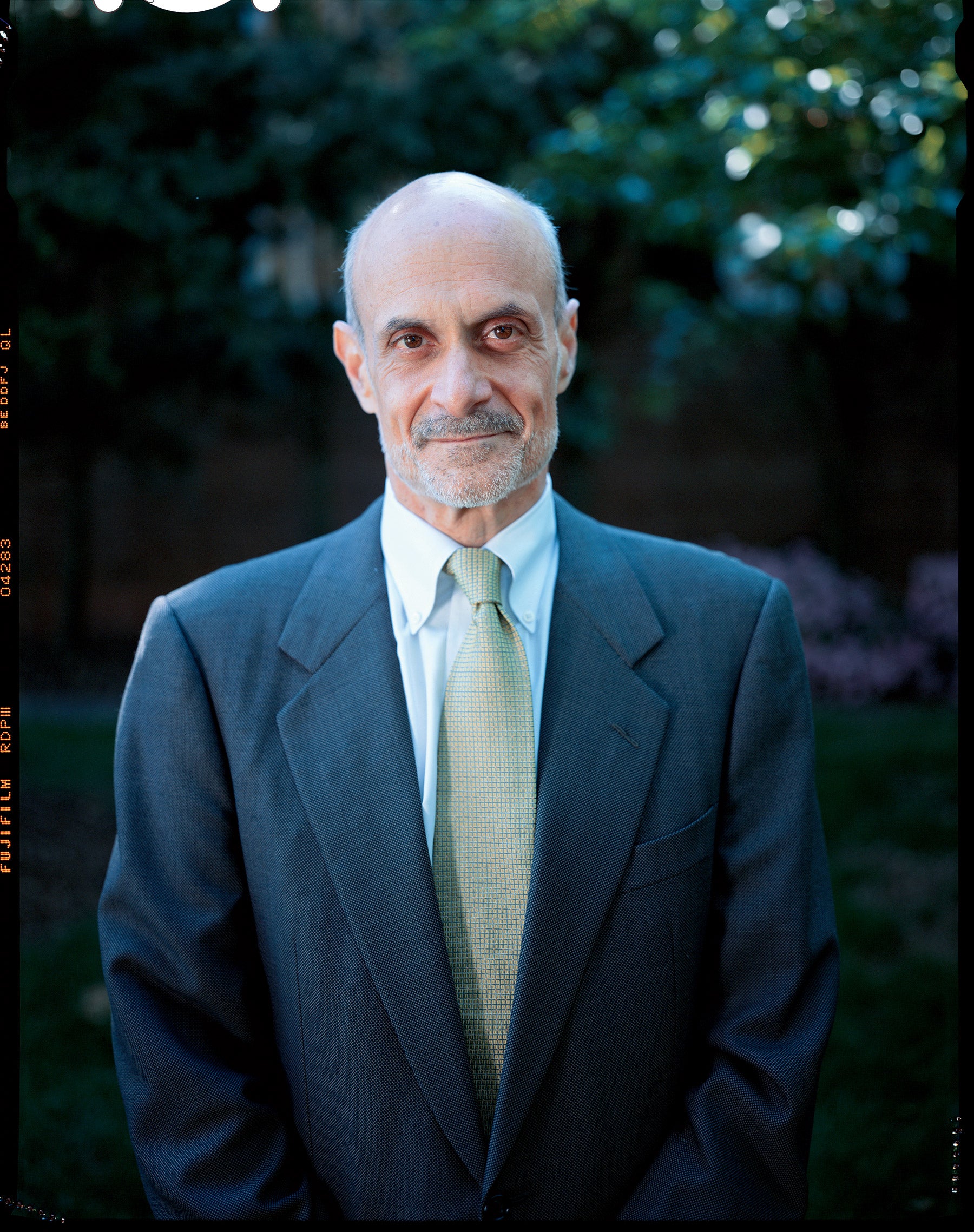

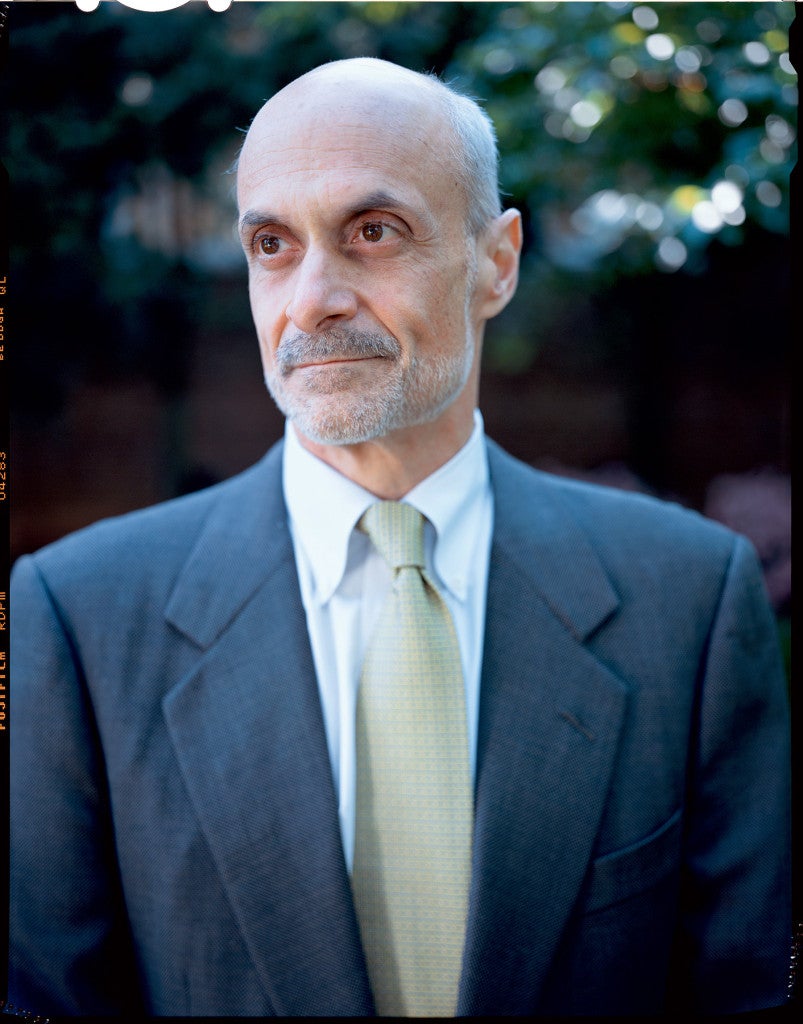

Can a veteran prosecutor whip the Department of Homeland Security into shape? Michael Chertoff ’78 has already started.

On Sept. 11, 2001, even before the attacks from the skies over the Eastern seaboard had ended, Michael Chertoff ’78 was making some of the government’s first critical decisions in reaction to what was turning out to be the worst criminal act in U.S. history. As head of the criminal division of the U.S. Department of Justice, it fell to Chertoff to lead the government’s law enforcement efforts until the attorney general, John Ashcroft, could return from an out-of-town trip.

In those first few hours after the attacks, Chertoff, a career trial lawyer and prosecutor, got a brief look at what it’s like to manage the response of a massive government bureaucracy made up of multiple law enforcement agencies during a national terrorist emergency. What he didn’t realize was that he was also getting a first glimpse at his own future.

That future became clear earlier this year, when President Bush handed him the job of running the Department of Homeland Security, a sprawling conglomerate of 22 agencies and 180,000 employees tasked with guarding the nation against further attacks.

Chertoff has taken the helm of a department plagued by organizational problems and the bureaucratic challenges caused by consolidating so many disparate agencies under one roof. He arrived there on the heels of a report by DHS’s former inspector general, Clark Kent Ervin ’85, blasting the department for poor financial decisions, wrongheaded allocation of resources, inadequate precautions at the nation’s ports and airports, and unsatisfactory integration of terrorist watch lists and databases from its component agencies.

In short, the challenges he faces are immense, as Sen. Judd Gregg, R-N.H., bluntly reminded him at an April hearing.

“Were this agency admitted to an emergency room, it would be considered to be in extreme distress,” Gregg said.

Chertoff’s supporters say the patient is in good hands, and that the department will be well-served by his considerable experience as a trial lawyer known for intense, hard-nosed advocacy, occasional elbow-throwing and an inclination to question assumptions through searing cross-examination. He also brings vast knowledge of criminal law and procedure, including a strong awareness of the constitutional rights implicated by government surveillance, searches and seizures–things his department does every day.

But, as much as all of that will help him, the experience that he will draw on most, say observers who know him, is his service as the U.S. attorney for New Jersey and later as the top criminal lawyer at the Justice Department, where he learned to hammer out problems between federal, state and local law enforcement agencies sometimes known to compete as much as cooperate.

And, Chertoff’s roots in the Justice Department may lessen the chances of a replay of some recent tensions between DHS and Justice. His predecessor, Tom Ridge, and former Attorney General Ashcroft were known to clash, most recently over information sharing and which agency should issue and announce terror alerts.

Chertoff already displayed many of the traits touted by supporters when he was a Harvard Law student 30 years ago. He had barely arrived at HLS when his fierce advocacy and intensity first drew notice. He engaged Professor Duncan Kennedy in a running argument for two days during class, sparring with him over judicial enforcement of the District of Columbia’s rent-control law. “I was arguing for what we call judicial restraint,” Chertoff said in a recent interview with the Bulletin. “He was arguing for activism.”

Kennedy has no recollection of the exchange, but it stuck in the mind of classmate Scott Turow, who later described Chertoff as the brightest student in the section. (Turow is said to have used Chertoff as the basis for at least one of his composite characters in his book “One L,” although he declines to say which characters are based on which students.) “Chertoff was not reluctant to debate with anybody,” remembered Turow. “He was self-confident, assertive, but never obnoxious.”

After graduation, Chertoff clerked for Murray Gurfein ’30, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, who regaled him with tales from his own days of prosecuting mobsters under then New York District Attorney Thomas Dewey in the 1930s.

“I realized that the prospect of doing a case in court was the most exciting thing you could do as a lawyer, plus I was interested in public service,” said Chertoff. “The best place to do that was in a prosecutor’s office.”

After a U.S. Supreme Court clerkship with Justice William J. Brennan Jr. ’31 and a few years as an associate at Latham & Watkins, Chertoff landed in the office of another prosecutor with his eye on organized crime, Rudolph Giuliani, then the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York. Giuliani assigned the 32-year-old Chertoff the role of prosecuting the heads of New York’s top mob families. They employed what was then a novel legal theory, charging and trying a major case under the federal racketeering statute and proving that the heads of the families had conspired as part of an illegal racketeering enterprise called the “Commission.”

The threat of violence hung over the three-month trial from the start, says fellow prosecutor John F. Savarese ’81. Shortly before the trial began, one of the defendants, Paul Castellano, was gunned down outside a Manhattan steakhouse.

Savarese recalled Chertoff’s “quiet authority and mastery of the facts and sincerity that [came] through and really connected with the jury.” All eight defendants in the case were convicted. (One of them, Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, later quipped that Chertoff owed him thanks for landing him his next job, as first assistant U.S. attorney in New Jersey.)

Chertoff’s reputation as a relentless prosecutor grew with each case. The American Lawyer magazine noted his “Gatling gunslinger” style of questioning. The Weekly Standard said of his interrogations, “[He] can make smart people look stupid.”

In 1990, President George H.W. Bush picked Chertoff to be U.S. attorney for New Jersey, and, in the state where he was born and raised, Chertoff often outshined his former colleagues across the river in New York. He prosecuted several mayors on corruption charges and handled the made-for-tabloid case against Chief Justice of New York Sol Wachtler for threatening to kidnap his former lover’s daughter.

As a federal prosecutor with management responsibilities, Chertoff learned to address bureaucratic problems, especially how to bring multiple law enforcement investigative agencies into line and to be certain that everyone was pulling in the same direction.

William Barr, attorney general in the administration of the first President Bush, says Chertoff’s experience building bridges to and between state and federal law enforcement agencies will serve him well at Homeland Security. “It’s important for a leader to understand this is a field organization,” Barr said.

Chertoff’s success was noticed back at department headquarters, where Barr included him in his inner circle. “He was second to none,” said Barr, who turned to him for advice and help with the most controversial and complicated cases.

But it was the case of a kidnapped Exxon executive, Sidney Reso, that Chertoff says affected him most deeply. It was one of the rare instances when he had to handle a violent crime as it was unfolding. Chertoff comforted Reso’s family members after his body was discovered in a New Jersey forest.

Even after stepping down from the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Chertoff continued to serve as counsel in probes of public corruption and racial profiling in New Jersey. “He was just offended by [these things],” said former Assistant U.S. Attorney Walter Timpone, who attributes Chertoff’s zeal for public service to his upbringing as the son of a New Jersey rabbi. “He’s got a real sense [that] this is his way to give back to the community,” Timpone said.

In 1994, Chertoff took on his most controversial (and, as it turned out, least successful) assignment–as chief counsel to the Senate Whitewater probe of President and Mrs. Clinton. Critics accused him of leading an overzealous witch hunt that had little to show after dozens of witnesses and tens of thousands of pages of testimony.

Nevertheless, Chertoff calls the Whitewater assignment a fascinating experience in which he gained his first close-up exposure to the legislative branch. He acknowledged only that such investigations “can be very painful and difficult” for those on the receiving end.

Despite the controversy, his role in the Whitewater probe did not harm Chertoff in the long run. In 2001, President Bush nominated him to be assistant attorney general in charge of the criminal division of the Justice Department, and the Senate confirmed him nearly unanimously.

In that role, he led the Justice Department’s investigation of Enron and its accounting firm, Arthur Andersen. But most of his time was dedicated to helping formulate the Bush administration’s legal strategy for combating terrorism, including the decision to sweep up hundreds of foreigners on immigration charges. He also helped craft the USA Patriot Act and staunchly defended the government’s antiterror efforts.

“Are we being aggressive and hard-nosed? You bet … but let me emphasize that every step that we have taken satisfies the Constitution and federal law as it existed both before and after September 11,” Chertoff told a Senate hearing in November 2001.

At the top of the criminal division, Chertoff had to oversee all of the federal government’s prosecutions and coordinate many of its most sensitive and complex law enforcement investigations, including those conducted by joint task forces of federal, state and local authorities. In that capacity, he learned to deal with multiple agencies and jurisdictions, and to cut through bureaucratic entanglements as efficiently as possible. Barr and other supporters note that he is particularly well-prepared for similar challenges at the Department of Homeland Security.

After leaving the Bush administration in 2003, Chertoff softened his zealous defense of the administration’s antiterrorism policy, expressing some doubts about the indefinite detention of American citizens such as José Padilla as “enemy combatants” without filing charges against them or providing them with legal counsel. In an article for The Weekly Standard in December 2003, he wrote: “We need to debate a long-term and sustainable architecture for the process of determining when, why and for how long someone may be detained as an enemy combatant, and what judicial review should be available.”

“In retrospect,” Chertoff told the Bulletin, “there were some imperfections. People in the field were making split-second decisions under pressure. The policies were appropriate and completely understandable given the risk. But we learned we should do better.”

Chertoff’s publicly aired second-guessing of Bush administration policies did not stop the president from putting him on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit in 2003.

He was on that court for little more than a year when Bush turned to him again for Homeland Security, after the nomination of former New York City Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik imploded over allegations of personal and financial improprieties. Chertoff had the advantage of having already been vetted and confirmed by the Senate three times. He didn’t hesitate to accept when Bush offered him the job.

“Winning this war against terror is the great calling of our generation,” Chertoff told an audience at George Washington University in March.

Thus far, Chertoff has consciously taken a lower profile than his predecessor, Ridge, the former Pennsylvania governor who relished his role as the public face of Homeland Security. Chertoff seems slightly ill at ease with the public part of his job and the retail politics that go with it, but what he lacks in natural skills as a glad-hander he more than makes up for as a political operator, former colleagues say. “His personality is exactly what the department needs, given his reputation for sharp elbows,” said homeland security expert James Carafano of the Heritage Foundation. “The department needs a strong advocate.”

Chertoff won some early plaudits for his first weeks on the job. Like a senior prosecutor taking over a foundering case, he ordered a top-to-bottom review of how the department is structured and how it does its job. He brought in Michael P. Jackson, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s deputy secretary known for his managerial prowess. He also questioned the usefulness of the color-coded warning system adopted by Ridge.

Chertoff said he plans a “disciplined approach” to sharing information with the public, trying to balance the need to keep everyone informed with a desire to avoid undue anxiety or alarm.

“The public is mature. The public understands that even before 9/11, we faced violent disasters both man-made and natural,” he said. “There’s not perfect protection; there are no guarantees. We need to focus on events that might have catastrophic consequences.”

Chertoff admits he has plenty to learn and is still mastering the breadth of the department’s responsibilities, which span law enforcement, disaster preparedness, and science and technology. The job has required adjustments in his personal life, too. His wife, Meryl Justin Chertoff ’83, a homeland security expert, decided to leave her job as a government lobbyist. And Chertoff admits his two children would like to see more of him.

He insists that he doesn’t miss the courtroom. But his friends aren’t so sure. Said Savarese, “If there’s a way for the Homeland Security secretary to argue a case somewhere, I think he’ll find it.”