“The role of a criminal-defense lawyer is rarely comfortable, and never popular,” renowned defense attorney Jack T. Litman ’67 liked to say, “but it remains among the more noble professions.”

For the 85 Harvard Law students who each year participate in Harvard Defenders, a student practice organization in which they represent low-income clients in criminal show-cause hearings, that sentiment informs everything they do. Open to 1Ls and upperclassmen, Defenders over the past 66 years has assisted thousands of indigent people while offering students invaluable courtroom experience and exposure to the realities of the criminal justice system.

“I just ran into a former student who is clerking for a magistrate judge in federal court. I hadn’t seen her in a couple of years, and she said Harvard Defenders was the best thing she did in law school,” says John Salsberg, a criminal defense attorney who’s been the supervising attorney at Defenders for 35 years, and was chosen for a 2015 Dean’s Award for Excellence at Harvard Law School. “Now, if that isn’t gratifying, I don’t know what is.”

With clients facing charges ranging from minor misdemeanors to serious felonies, students argue before clerk-magistrates at these hearings, a pre-arraignment stage at which the state must show probable cause. If the clients prevail, criminal charges against them are dropped. If not, prosecution proceeds. As there is no right to court-appointed counsel in these proceedings, representation by the Defenders is one of the few options for those who can’t afford a private lawyer.

In 2013, Defenders represented clients in more than 145 show-cause hearings in 20 Massachusetts courts. Sam Dinning ’16, HKS ’13, vice-president of Defenders, was in court every other week last year, and expects the same this year.

“It’s an amazing experience to be only two weeks into law school and be in a courtroom already,” says Dinning, who plans to become a prosecutor, and joined Defenders as a 1L.

Litman, who died in 2010, was among the more illustrious Defenders alumni. His son Benjamin Litman ’06 also participated, and today is an appellate criminal-defense lawyer at Appellate Advocates in New York City. Defenders has launched the careers of many others in the criminal justice system including judges, magistrates, public defenders, and federal and state prosecutors.

“Defenders gave me the opportunity to represent real clients in real trouble, albeit usually not big trouble,” says David Deakin ’91, chief of the family protection and sexual assault bureau at the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office in Massachusetts. “I enjoyed every minute of it, and I learned a tremendous amount about courtroom advocacy—and about the basic humanity of many people accused of even serious crimes—from John [Salsberg] and his partner at the time, Jack Cunha.”

Though Deakin planned to become a defense attorney, he started his professional career in a prosecutor’s office and liked it. “Nonetheless, the skills that I learned from John and Jack in Defenders have been invaluable to me in anticipating how defense counsel will attack a case,” he says. Moreover, “the experiences that I had there in meeting clients and trying to understand them as individual human beings has helped me to try to understand the difference between defendants who are primarily bad and those who are primarily sad.”

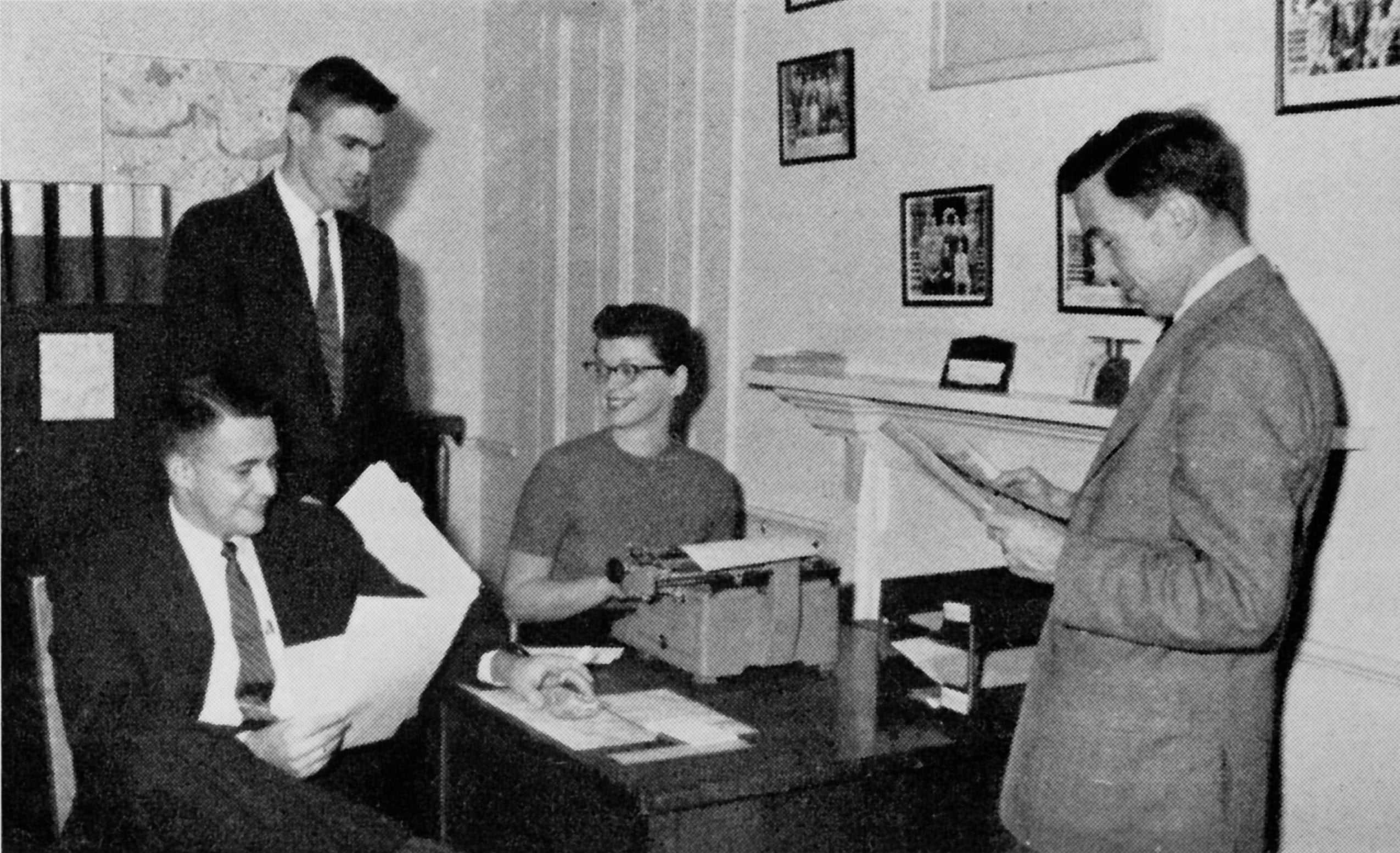

When it began in 1949, Harvard Defenders comprised ten 3L students providing representation to indigent criminal defendants in a broader context than show-cause hearings. A year later, HLS granted it official recognition, a $500 budget, and an office in Gannett House. Today, Defenders has 85 students each year—JDs and also LL.M.s—and limits itself to show-cause proceedings. Many students who join as 1Ls find it so rewarding they continue throughout their law school careers, even though they often put in many hours but do not receive academic credit. (Clinics offer academic credits, but student practice organizations do not).

“There’s a lot of enthusiasm for doing this sort of work, which speaks well of who Harvard Law School is admitting, and also of the fact that students are interested in the social issues this work presents,” says Salsberg. In turn, students praise Salsberg for his humor, breadth of experience, teaching skills, and generosity with his time. He takes phone calls from them at all hours of the day and night.

Under his guidance, and working in teams, students “build trial skills including learning how to read a police report, investigate a case, cross examine witnesses and police officers, and put together a legal argument,” says Tori Anderson ’16, Defenders president, who interned at public defender offices during law school summers and will become a public defender next year. She especially values the “ability to positively impact our clients’ lives by sparing them the enmeshed penalties of a potential criminal conviction.”

The sense of community and teamwork are key. “I love it,” says Dinning. “Part of prepping for every hearing is going over your case with 10 to 12 people and your supervisor, going over the law, what are the most persuasive arguments and figuring out what will be effective. You’re with a group of really interested students and a supervisor with a crazy amount of experience. It’s a pretty cool opportunity.”

Three years ago, Benjamin Litman and his brother Sacha Litman HKS ’03 established the Litman Fellowship at Harvard Defenders in honor of their father, who was perhaps best known for representing “Preppy Killer” Robert Chambers and was respected for his zealous advocacy on behalf of unpopular defendants. HLS Professor Alan Dershowitz called Jack Litman “one of my best students” and “one of the great criminal lawyers of the past half century.”

“Sacha and I created the fellowship as a way to honor not only our father’s legacy, but his firm belief that the next generation of criminal-defense lawyers should be exposed early on to the sometimes harsh realities of the profession,” says Benjamin Litman. “Like my father before me, I learned these lessons as a member of Harvard Defenders, and they have stayed with me to this day.”

The Fellowship provides stipends to three students each summer to work in the Defenders office; before it was created, students worked without getting paid. “It’s great because they get so much experience and have so much autonomy,” says Maria Leister, administrative director of Defenders. “By the end of the summer, they really know the courts, and have had so much client interaction. On the client side, it’s a wonderful program because we can keep the office running over the summer.”

The fellows are required to write and present a paper on a criminal justice issue at the Litman Fellowship Symposium, held each fall. Last year, Defenders celebrated its 65th anniversary at the Symposium, which was sponsored by the HLS Milbank Tweed Fund and the Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs. Keynote speaker Debo Adegbile, a celebrated civil rights lawyer, speaking to the value of Defenders, said, “Lawyers make a difference, and the absence of lawyers makes a difference, too.”

As Benjamin Litman likes to point out, Adegbile also observed that criminal defense attorneys are “the mark of a truly civilized society.”