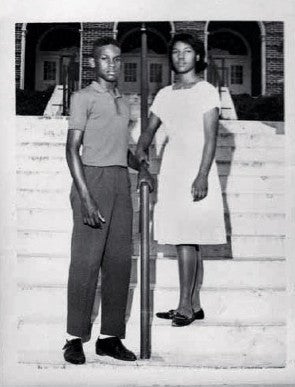

The summer before he went to Harvard Law School, Bishop Holifield ’69 protested outside Tallahassee City Hall with his sister, Marilyn Holfield ’72 to persuade the city to reopen swimming pools it had decided to close rather than integrate.

Marilyn picketed City Hall with a sign that read “My bathtub isn’t big enough,” and Bishop organized volunteers to make phone calls to registered voters. Their concerted efforts paid off when the city voted to open the pools to all.

Since then, the siblings have pursued separate paths toward justice but have carried with them their common experiences of living in the South during the civil rights movement. In honor of their social justice work and pioneering spirits, they were recently awarded the Gertrude E. Rush Award from the National Bar Association.

Years before the Holifields worked to open integrated pools, they were influenced by stories of lawyers who had fought for social justice. One day in the spring of 1963, their mother took the day off from work to see Constance Baker Motley argue a school desegregation case before a U.S. District Court.

“My mother came home and told us about this remarkable black female lawyer,” Marilyn said. Not long after the ruling, Marilyn would be among the first three black students at a previously all-white high school.

“It was a very hostile environment from the day I got there to the day I left,” she remembered. “I became very familiar with the N-word.” It had been her choice to attend the school, but she had no sense of the danger she faced.

“It was the epitome of a one-person civil rights movement,” she said with a laugh.

Though it was difficult, Marilyn was glad she went to Leon High School. “It brought out a spirit of tenacity and determination to push forward,” she said. They are qualities that have contributed to her considerable success as one of few black students at Harvard Law in the early ’70s and, in 1986, as the first black woman to become partner in any major Florida law firm.

Her firm, Holland & Knight, had never hired a black lawyer before she joined them in Tampa in 1981, she said. “It was more as if large, white law firms were clubs for white lawyers.” She felt the isolation but not the hostility she felt in high school—nevertheless, it fostered in her the same determination to succeed.

Her main focus at Holland & Knight is business litigation. She has also done pro bono work, including representing plaintiffs in a class-action suit against a housing complex that discriminated against minorities, landing them a multimillion-dollar settlement.

This type of case wasn’t new to Marilyn. Right out of HLS, where she was one of the editors of the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, she took a job with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. There she worked to integrate a prison in Georgia where black inmates were being abused, and to stop a manufacturing company from assigning the least desirable jobs to African-American workers.

When Bishop was a 1L, he urged his sister to apply to law school. He had wanted to work in civil rights law ever since he read a biography of Clarence Darrow.

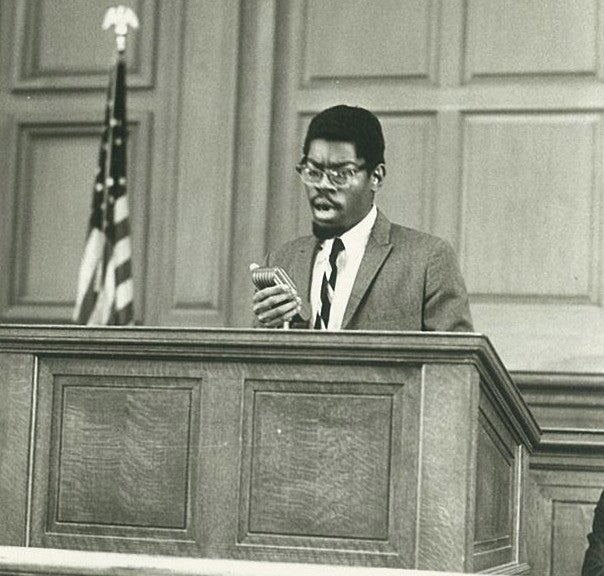

While at Harvard, Bishop co-founded the Harvard Black Law Students Association, which helped address the underrepresentation of black students and the absence of black professors. They also worked to influence what the school taught.

“We tried to make the curriculum more relevant for what people who weren’t going to practice on Wall Street might need,” Bishop said. For example, instead of teaching only creditors’ rights, the association lobbied for an emphasis on debtors’ rights.

He saw such issues as civil rights matters. “It became clear to me that the civil rights struggle transformed itself from being able to eat at a lunch counter to a struggle to have economic opportunities, health care and educational opportunities.”

Bishop dedicated much of his career to these efforts. As general counsel for Florida A&M University, where he worked from the mid-1970s until his retirement in 2002, he fought to get the state to return a law school it had taken from FAMU, a largely black institution, and given in 1968 to Florida State University, a largely white school.

He began this effort in 1985 and prevailed in 2000. “This was really a monumental success against overwhelming odds,” Marilyn said. “A struggle Bishop led for 15 years against an entrenched establishment.”

Bishop said much remains to be done. He’s troubled by rising economic inequality, voting rights violations, health care deficiencies, the school-to-prison pipeline, and the state’s notorious Stand Your Ground law—issues that have replaced the discrimination at swimming pools and factories against which the siblings first fought.

“I think our generation felt that we could change the world,” Marilyn said, and then paused. “In some respects, we did.”