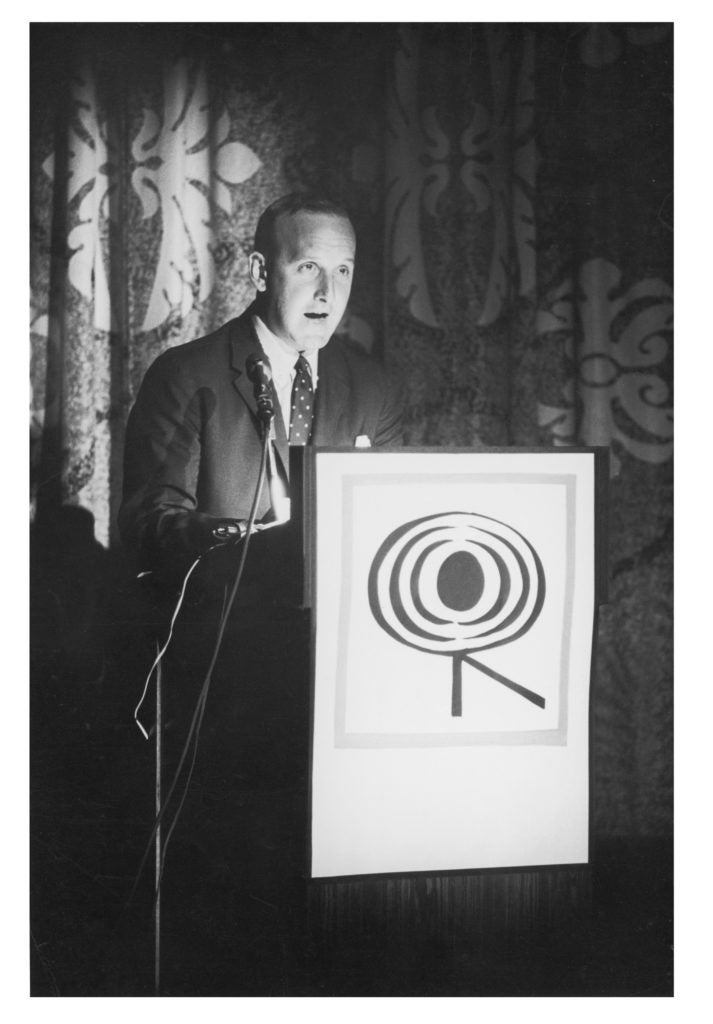

When Clive Davis LL.B. ’56 comes on the line, one of the first things he does is to ask what kind of music I listen to. Davis’ legendary golden ear, the knack for knowing what people want to hear, have been a constant in his illustrious five-decade career—running Columbia Records in the ‘60s and ‘70s, founding Arista in 1974 and J Records in 2000, and at age 85, still guiding the industry today as the chief creative officer of Sony Music Entertainment.

He returned to Harvard Law School this month as the honorary chairman of the HLS in the Arts celebration. On Saturday, Sept. 16 he was in attendance at the Boston premiere of “Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives,” a film based on his 2013 autobiography. The film was recently shown to much acclaim at Radio City Music Hall for the Tribeca Film Festival, where Aretha Franklin and Earth, Wind & Fire performed afterward in Davis’ honor. The Harvard showing was preceded by a reception at 5pm, and followed by a half-hour Q&A session at 8pm.

In advance of his Harvard appearance, Davis spoke with us by phone about some of the key moments in his career.

I think a lot of our readers would be surprised to learn that you came to Harvard Law School with no intention of making a life and career in music.

Oh, I had none, zero. It was the furthest thing from my mind. I had come there right after my college years. My parents had passed away and I had no money, I had the munificent sum of four thousand dollars, I was incredibly grateful for the scholarship that I had and that paid for my tuition, and I really was there to prepare for a legal career—and that only.

Did that change once you began working for the Columbia label?

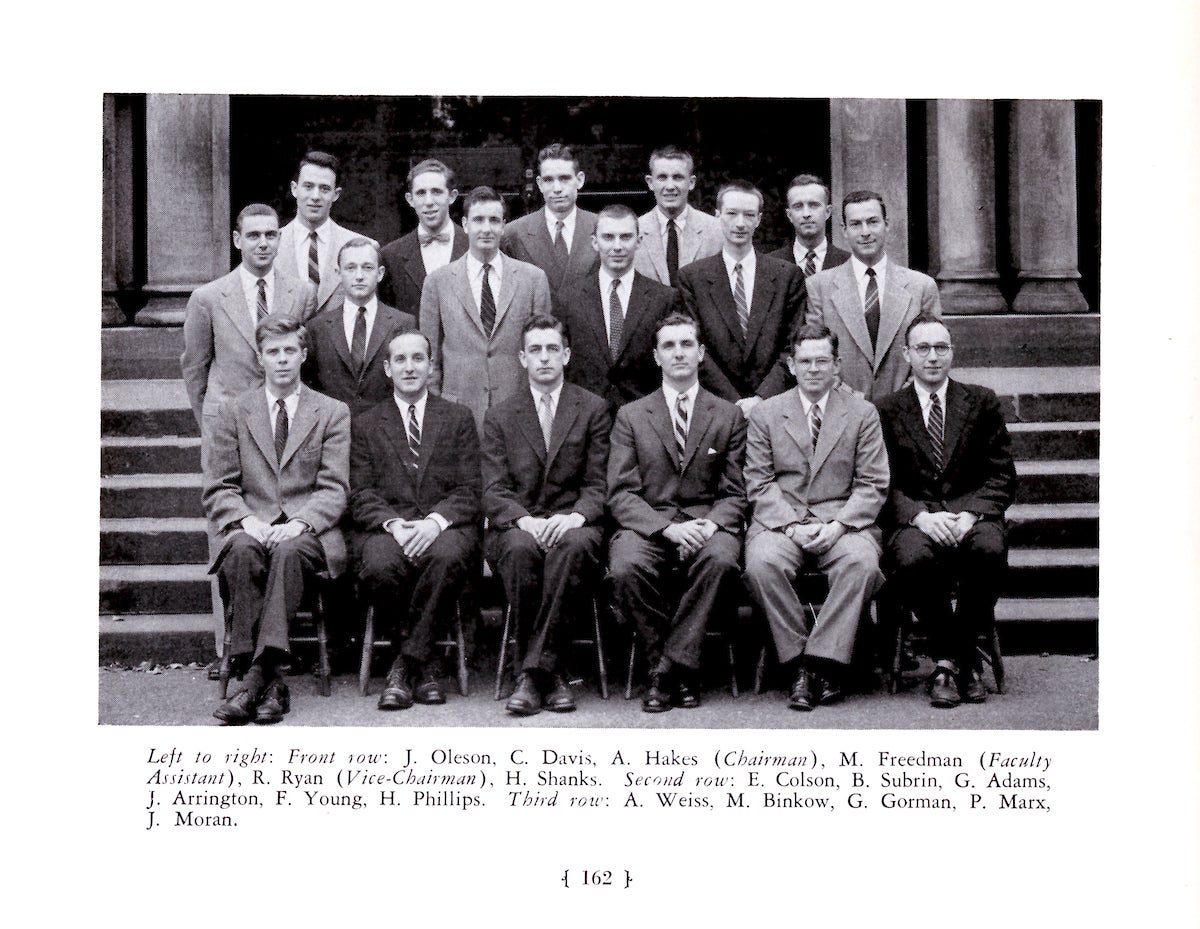

Luck plays an incredible role in my transition into music. First of all I had a choice when I was at the law school of either law review or the board of student advisors. I chose the board because it paid five hundred dollars—I needed that at the time. Coming from New York I thought I would go, and indeed did go, to a relatively small firm—a large firm at the time was only 50 to 100 lawyers, and my take-home pay was $86.50 a week. I went to this small firm for about a year and a half during which time their largest client merged into the surviving company of the merger, and it was clear how vulnerable they were to a major change in the position. Though they were happy with me, they were cutting back two of the associates. So if that hadn’t happened, I might still have been there.

[Davis next joined the firm Rosenman, Colin, Kaye, Petschek, and Freund and worked on contracts for their client Columbia Records; he was ultimately appointed the label’s vice president and general manager by its president Goddard Lieberson].

I said yes despite the advice of my senior partner who thought my Ivy League background would be too ivory tower-ish for the record industry. But I had grown up in Brooklyn, in a melting pot neighborhood. I went to PS 161, I went to NYU. It was only the last three years of life where I entered the Ivy League of Harvard. So yes, I took it—but again, not thinking in any way that I would be involved with music. I liked music but I listened in a very ordinary way, like anyone would listen to the radio. I never collected records, or wanted to be a fly on the wall in a studio. I did adopt the philosophy that if you’re going to be counsel to a company, you learn everything you can about a business. But even then it never occurred to me that I would be on the music side.

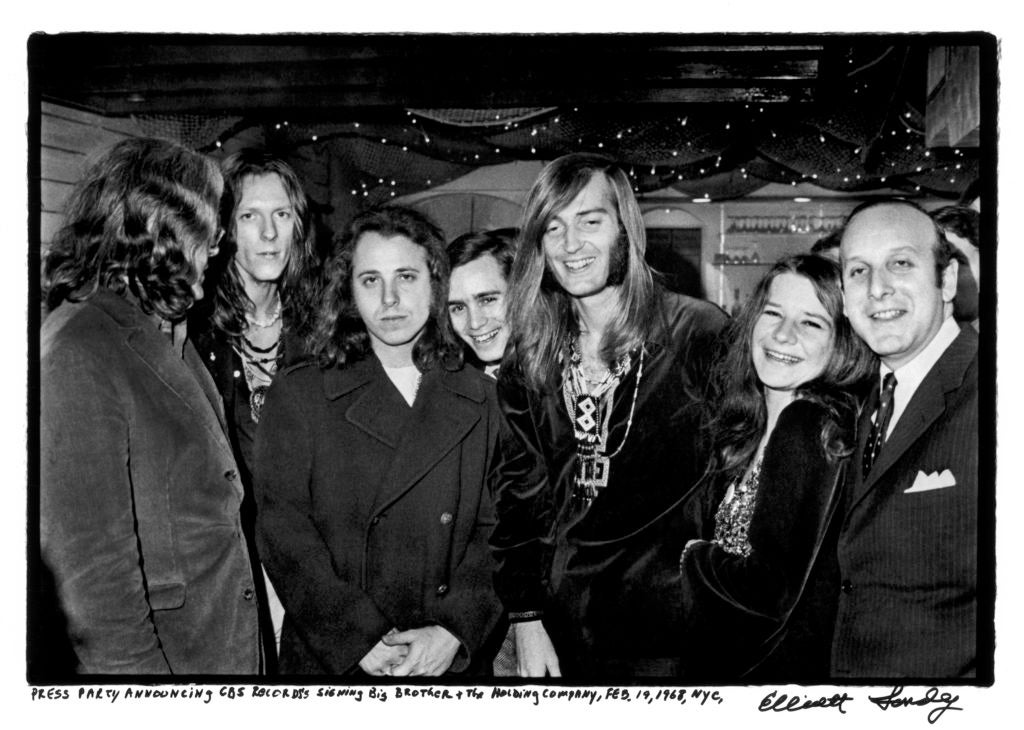

But we’re talking circa 1965 here, and at that point you were only a couple of years away from signing Big Brother & the Holding Company (with Janis Joplin), Santana, Chicago and many others to Columbia. So clearly something clicked into place.

It was the epiphany at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. That was the life-changing event. I saw that what was making Columbia Records was mainly great Broadway shows like “My Fair Lady” and “The Sound of Music,” and middle-of-the-road pop singers—Barbra Streisand, Andy Williams. Though we did have Bob Dylan he was more a songwriter for other artists, not a star in his own right yet. Simon & Garfunkel were just releasing their first single, “The Sound of Silence.” But I found myself at Monterey in the afternoon, prior to the entertainment of Simon & Garfunkel, the Mamas & the Papas, other artists that I knew…I saw this revolution in culture and philosophy: The Haight-Ashbury scene with love, peace and flowers. I had no idea that this revolution was flowering. So I was there in my tennis sweater—I was the costume freak surrounded by everyone with flowers in their hair.

It was right after that that I realized I had to go by my instincts. So I began and signed Big Brother & the Holding Company, the Electric Flag with [guitar great] Mike Bloomfield. And a few weeks after I got back, I auditioned Blood, Sweat & Tears at the Village Gate. All those artists set me on my path to immerse myself in music.

You’ve never been associated with a single style of music, and I think the early years of your Arista label are testament to that. Not many people would have Barry Manilow and Iggy Pop on the same label.

At that time Columbia was the number one label in the industry, hitting on all fronts. And I wanted to make Arista a major label—How do you do that? That led me to explore the “repertoire” side of the term ”artists and repertoire.” The first record on Arista was “Mandy,” a song I found and gave to Barry Manilow. Barry allowed me two songs on every album, but those were the songs that became the signature hits. And since Barry allowed me only those two songs on an album, I had a backlog of songs which I could give to other artists.

That started me on the entertainer side, which came to coexist with the rock signature side. I was gifted by the Grateful Dead coming to Arista when we were relatively new. I told them that their vision of starting their own label would not make it; when that turned out to be an accurate prediction they came to Arista. So I was able to continue in the rock tradition with them, Patti Smith, the Kinks, then later broadened it to Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. But you don’t become a number one label with punk rock and new wave, because that doesn’t sell in the same numbers as an album with a hit single.

This brings us to the million-dollar question: How can you tell when a song is a hit single?

It’s a combination of instinct and feel. You’re really identifying the nature of the musical hook: How accessible is it, how memorable? Can you hum it or sing it back after you’ve heard it once or twice? You are appraising the lyric, and I am a very big lyric guy; you’re considering their impact. So it’s not a scientific thing, it’s a visceral thing. And I have been very lucky over the years; I found every song Whitney Houston ever recorded. The film is called “The Soundtrack of Our Lives,” there are 105 music cues in it, and I submit to you that they are the soundtrack of my life.

The film makes clear relationships that I had with artists, and that was certainly a central key one. It’s a hard one for me to watch because it captures the uniqueness of Whitney. All those prodigious vocal gifts that she had in its fullest flower and its breathtaking way. But it doesn’t spare her downfall of being afflicted by a drug addiction. And so the film is very compelling in its depiction of how Whitney lost that battle.

We could name a lot of multi-million selling artists you’ve been involved with, from Whitney Houston to Santana. But I was wondering if there were any that fell through the cracks who were especially close to your heart.

There are artists who could have been bigger if their thought process was different. For example, I always felt that Melissa Manchester could be up there with a Barbra Streisand or a Bette Midler. She had some big hits, two of which she wrote—and to supplement that, the way I did with Barry Manilow, I gave her “Don’t Cry Out Loud,” a big, big song. But she at the time didn’t want that kind of career; she wanted to be more like Joni Mitchell. There were two on Arista in particular that I thought could have made it. One was the Alpha Band, who had T-Bone Burnett [later a successful producer and record executive]; and there was the Funky Kings, with Jack Tempchin who’d come up with great songs for the Eagles. But he didn’t come up with them for the Funky Kings, and I never give songs to self-contained groups.

I can’t let you go without asking what advice you’d give to anyone studying at HLS who aspires to become the next Clive Davis.

Look, I think that music is a very enriching fulfilling and rewarding career. Obviously two years ago there were question marks after the digital revolution— when the public was used to getting their music free, which is certainly contrary to our capitalistic system and to the rewarding of creative people. But I have always believed that music is a wonderful creative opportunity, which is why I have endowed at NYU the Clive Davis Institute for Recorded Music. When I grew up there were only little elitist music schools, studying only jazz and contemporary music. I believe that music can be a wonderful career. And now with streaming and the availability of music once again, there is healthy upward glow to it. So if it is part of your life stream I would encourage making a career of it.

At Harvard Law School on Sept. 16, Clive Davis, who served as Honorary Chair of HLS in the Arts, returned to HLS for the Boston premiere of “Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives,” a documentary based on his illustrious five-decade career. A Q&A session with Dean John Manning followed the screening.