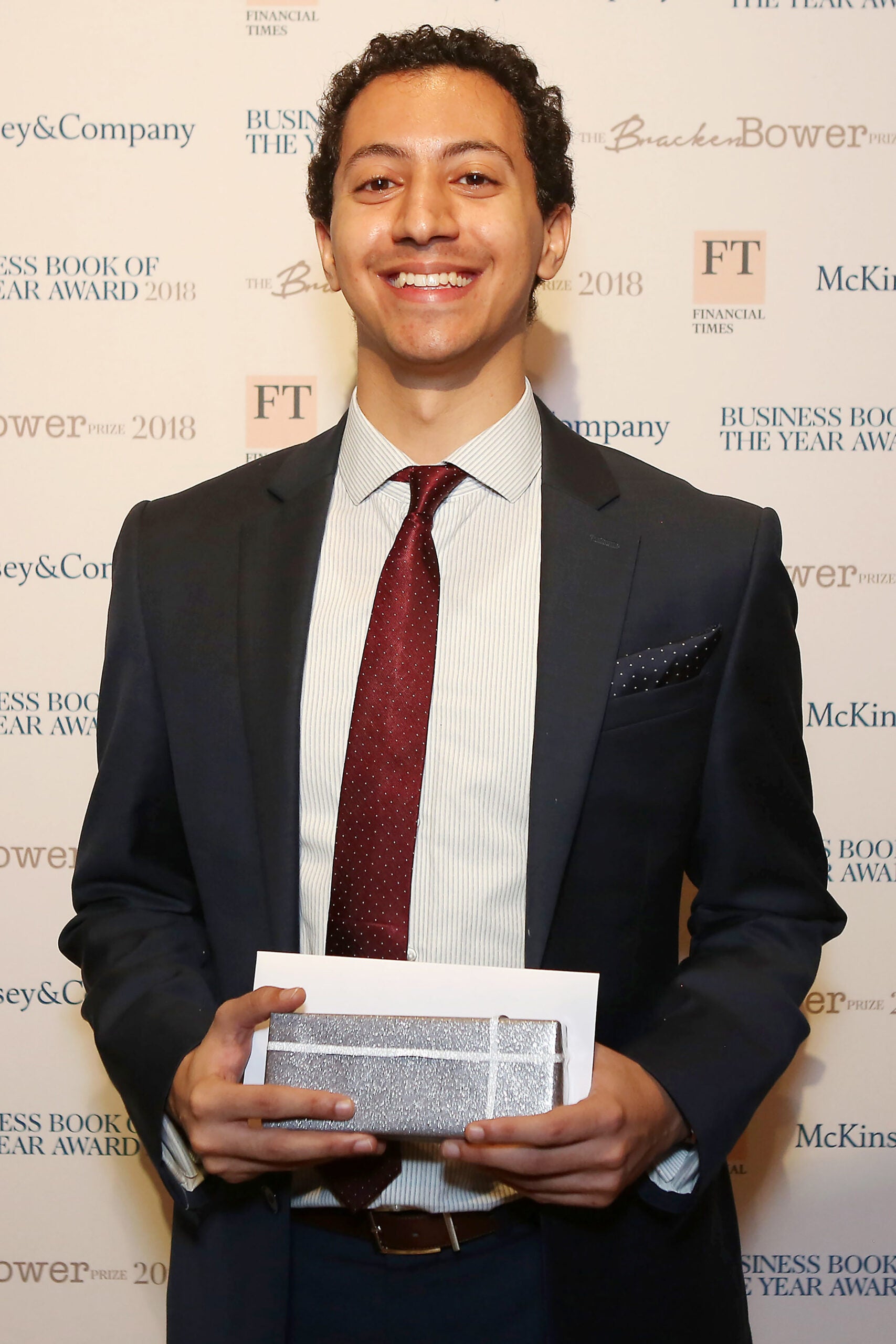

When third-year Harvard Law student Andrew Leon Hanna hears immigrants depicted as criminals or charity cases, he thinks instead of his parents, Nosshey and Afaf Hanna, who immigrated to the United States from Egypt three decades ago. Their lives helped inspire Hanna’s book proposal, “25 Million Sparks”, which recently won the 2018 Bracken Bower Prize from the Financial Times and McKinsey & Company, for the best business book proposal from an author aged 35 or under. Hanna, 26, plans to use the prize money—15,000 British pounds, or about $19,000—to travel to the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan and other places around the world where refugees who’ve fled war and persecution have built new lives with their creativity. He’s in talks with agents and editors about his book proposal.

Hanna—a Harvard Defenders team leader, Harvard Law Review editor, and the North Africa chair of the Harvard African Law Association—recently won HLS’s Irving Oberman Memorial Prize for Law and Social Change for his soon-to-be-published law review article arguing that solitary confinement is unconstitutional. With his classmate from Duke University, producer/director David Delaney Mayer, he is in the process of cofounding the Harvard Innovation Lab startup DreamxAmerica—combining filmmaking about immigrant entrepreneurs with investments in their businesses. Before HLS, he worked for McKinsey & Company, where he directed the global youth employment initiative Generation in Houston, Tex. and Jacksonville, Fla., his hometown. Prior to that he interned at the White House, where he worked on policies involving veterans’ mental health care and unaccompanied children.

How his family’s history influenced his book idea:

My parents immigrated from Egypt to the United States about three decades ago. They’re incredible people who’ve given their entire lives to me, my sisters, and our community in Jacksonville. I know everything I have is thanks to their story. So when I see immigrants portrayed in a way that doesn’t do justice to their dignity, I often think of my parents. And in terms of entrepreneurship specifically, my dad started a successful primary care practice in Jacksonville. He’s been running it for 30 years, has served thousands of patients, and wrote a book on how to improve the U.S. health care system [“Dying of Health Care,” which Andrew helped edit]. Meanwhile, my mom, a pre-school teacher, has shaped and inspired countless kids’ lives. So I know firsthand the type of transformational community impact immigrants can make. The same is certainly true for refugees in particular.

Where he got the idea to write about refugee entrepreneurs:

There’s a Harvard Business Review article explaining that immigrants have double the rate of entrepreneurship [as natural-born citizens]. One reason is that they are often discriminated against in the workforce, so they feel compelled to start something on their own. Another is that they have cross-cultural experiences, and that often helps you think of new customers and new ways of doing things. And another is the ability to deal with risk, the courage to take chances.

Refugees in particular are the most extreme entrepreneurs—they often possess the strongest qualities of innovators, including truly remarkable resilience of spirit. So rather than lamenting today’s historic refugee crisis, looking down upon refugees, or refusing to welcome them, we should join together and help catalyze refugee entrepreneurs’ ideas on the path to inclusive economic growth for all of us.

How his Christian faith influenced his project:

It’s important to me that the Bible teaches to care for the “stranger.” Jesus spent a lot of his time with the most disconnected, the outcasts ignored by society. He loved the unloved. He made sure people around him were appreciated for their equal dignity as human beings, not reduced to a single storyline. This naturally has implications for how we speak about and engage with refugees today.

How his book will respond to media coverage of the refugee crisis:

Media coverage of immigrants, particularly refugees, is not really telling the full story. The folks fleeing Central America in the media right now, for example—they’re portrayed as one-dimensional human beings. They’re either victims or villains.

The media often portrays refugees, especially those in camps, as hopeless human beings who desperately need our support. While there’s certainly truth to the fact that we should be supporting refugees because of the persecution that folks are fleeing, that’s not the full story. That story does not recognize their courage, self-sufficiency, and full humanity.

Meanwhile, the media also very frequently paints refugees arriving in host countries as threats to our way of life. There the narrative is: we need to shut off our borders with a wall or leave folks at the shore to make sure that refugees aren’t taking from what we have in this country, tearing at our moral fabric, and potentially introducing crime, terrorism, and drugs. That’s inaccurate. Statistics show refugees, very quickly upon coming to the United States and other host countries, begin contributing more to the public budget than they take away. That’s not to mention the infusion of cultural diversity, new ideas, joy.

What he’ll do with the prize money:

The main thing I’m going to do is use it to travel, ideally to three different refugee camps, to talk to folks and hear their stories. The first one is going to be Zaatari in Jordan, one of the world’s largest refugee camps and host of 80,000 Syrian refugees. They’ve given birth to 3,000 new ventures that generate a total of $13 million a month in revenue. And refugee camps are just half of the book’s focus; host countries are the other half. For that I plan on talking to refugee entrepreneurs in the United States, Western Europe, Lebanon, and elsewhere.

On his work at HLS with former dean Martha Minow, former judge Nancy Gertner, and Assistant Professor Andrew Crespo:

I think law school has been super-pivotal for me gaining confidence as a writer, and learning how to infuse dignity in my writing. You learn how to do the rigorous analytical stuff during 1L year, but what takes writing to the next level—and what Dean Minow, Judge Gertner, Professor Crespo, and others have helped me with—is how you make analytical arguments while also appealing to our common humanity and our common aspirations for society. I’m excited to bring the resources I’ve benefited from at Harvard to immigrant and refugee communities through this book and through DreamxAmerica… and I believe we have a lot to learn from those communities as well.