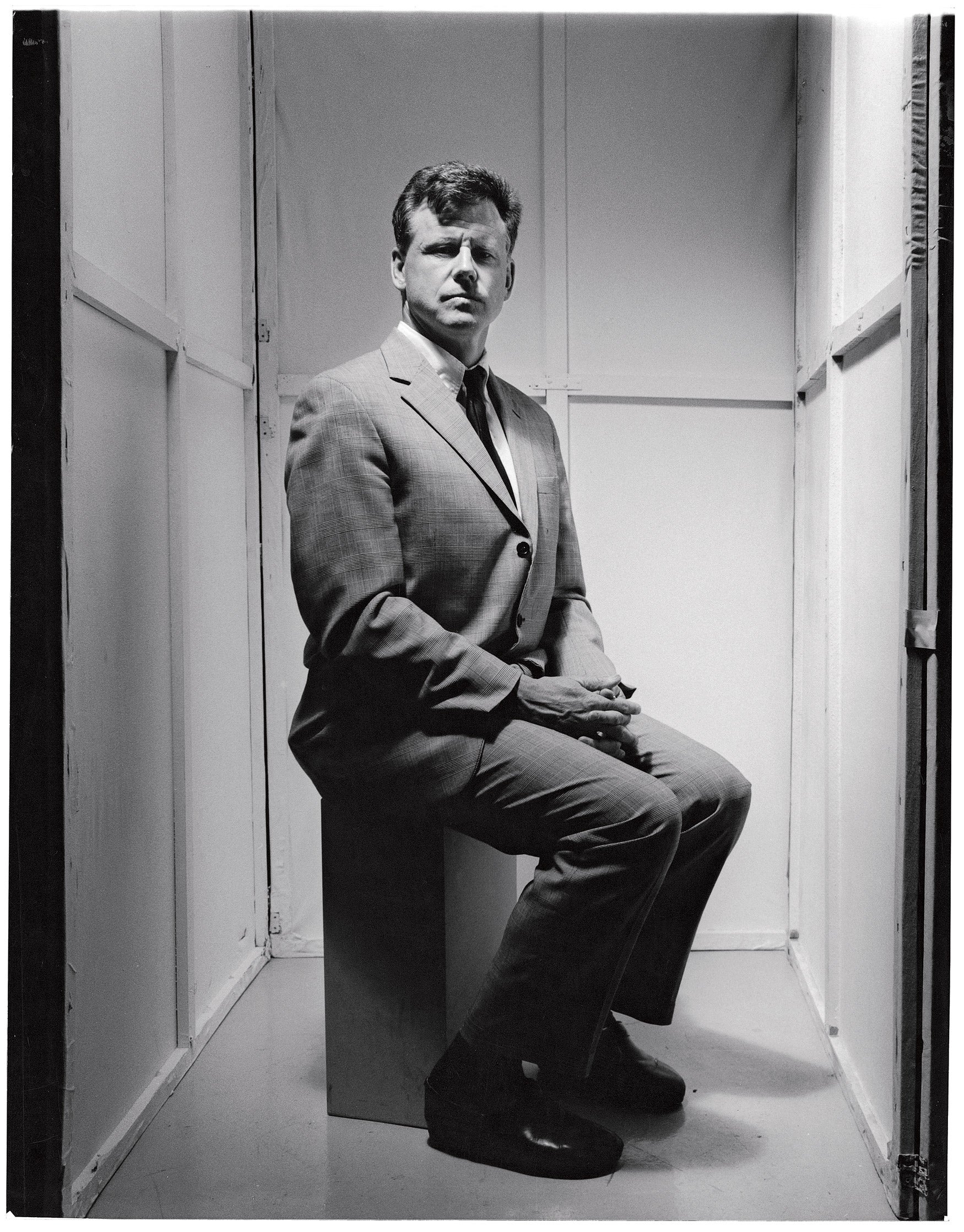

Sabin Willett ’83 traveled to the state of limbo

By Mary Bridges

Sabin Willett leads a double life as a lawyer. Most days, he works on bankruptcy litigation in the Boston office of Bingham McCutchen. He likes the work. Really, he says, sitting in a conference room with a sweeping view of Boston harbor.

In his other legal life, you might find him near the naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, which he describes as “a sleepy little town [with] a couple of traffic lights, stores and a golf course that has iguanas on it.”

Willett got involved with the legal issues surrounding the U.S.’s naval detention center at Guantanamo Bay after a friend urged him to attend a panel discussion on the legal status of enemy combatants.

“I came away kind of shocked from that,” Willett said.

He contacted friends and organizations involved in defending enemy combatants and, with other attorneys at Bingham McCutchen, decided to take a case pro bono.

One organization asked if Willett would take several Uighurs as his clients. Willett’s response: “What’s a Uighur?”

Uighurs (pronounced WEE-gurs), as he learned, are ethnic Chinese Muslims from northwestern China. There are an estimated 8 to 10 million Uighurs, and at least 20 were being held at Guantanamo.

Willett’s clients remained there for four years after their capture by Pakistani security forces, even after the military conceded that they posed no threat to national security. A Combatant Status Review Tribunal had determined in March 2005 that the Uighurs should be classified as NLECs, or “no longer enemy combatants.”

Why did they remain at Guantanamo for another 14 months?

Willett asked the courts the same question. In a December 2005 decision, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia agreed with Willett that the Uighurs were being detained unlawfully, but concluded that the courts lacked the legal authority to devise a solution.

His clients could not be sent back to China because of fears of persecution by the communist government. They were denied asylum in the U.S., and no country would agree to take them until the military announced on a Friday in May—three days before a scheduled appeal hearing—that the men would be sent to Albania.

“I didn’t know anything about [the decision] until that afternoon,” Willett said.

While his clients were overjoyed at leaving Guantanamo, a tangle of new problems quickly emerged. They were sent to a refugee center, but Albania lacks a Uighur population to provide a support network, and there are no concrete plans for transitioning them to civilian life. Meanwhile, China has said it wants them back.

“I have no idea how it’s going to work,” said Willett, who visited the men shortly after their arrival in Albania.

To Willett, these developments were the latest round of frustrations that began as soon as he started the case. His legal team had to initiate the lawsuit without ever meeting the clients.

“We knew nothing. The military would tell us nothing. All we knew was what we could find on the Internet,” he said.

He said the work was exhilarating—the kind of case that “can really get the blood pumping.” It landed him a profile in The Boston Globe in February and interviews on public radio programs.

But it was also maddening, particularly when compared with litigating bankruptcy cases.

“Stuff happens in [a bankruptcy] court, and it’s only about money. I’ve got a case about whether somebody can be held behind razor wire, and I can’t get anything to happen.”

Willett says he became friends with the men during the process of representing them. “At this point, when we meet A’del [one of the clients], it’s bear hugs.” He hopes to help them connect to a larger community of Uighurs somewhere, but because the men are no longer at Guantanamo, “we’re out of our competency now.”

Willett, who has also published three novels, said the case has been sobering: “I realized how insignificant I am.”