Two-day conference reflects on corruption in government and politics

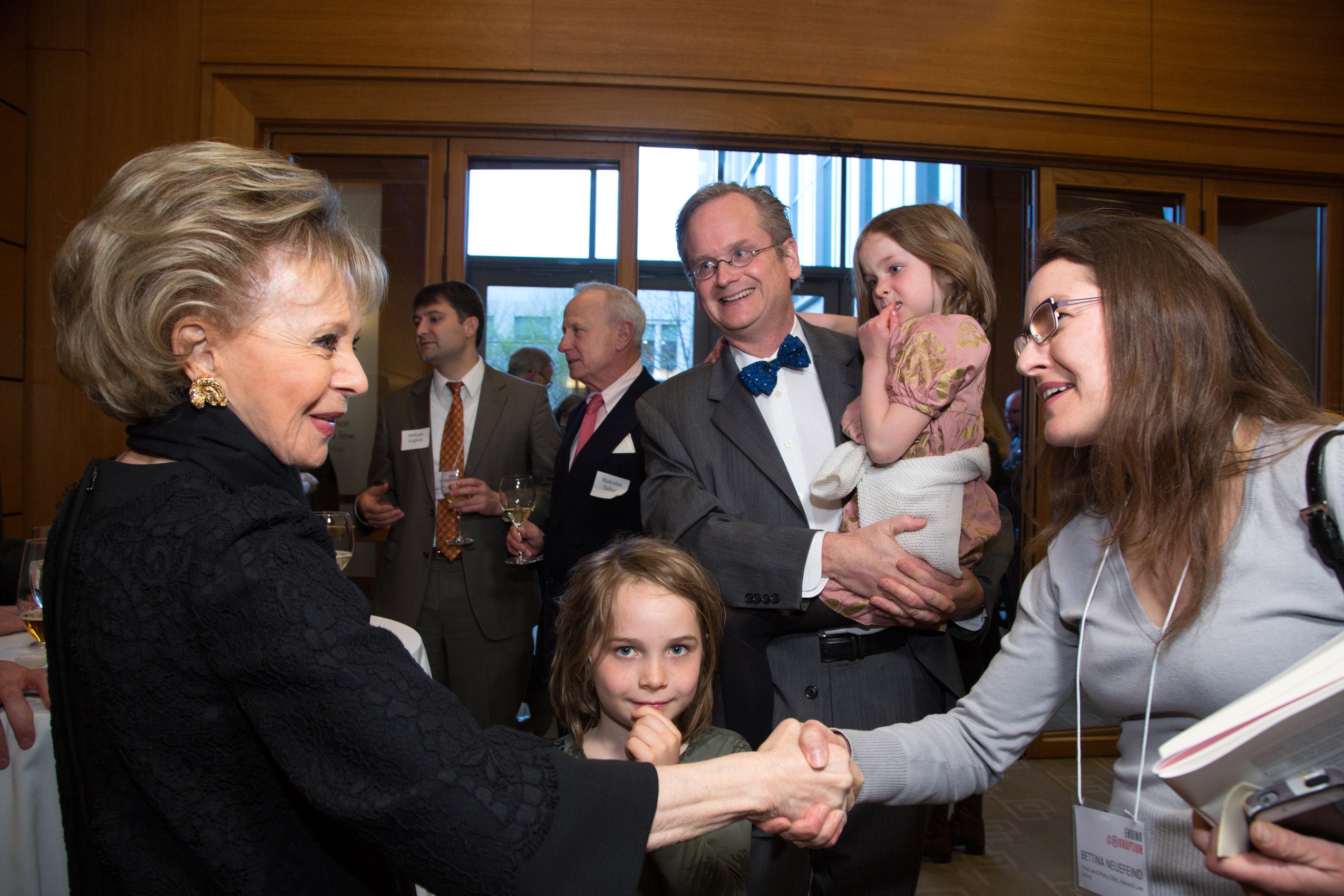

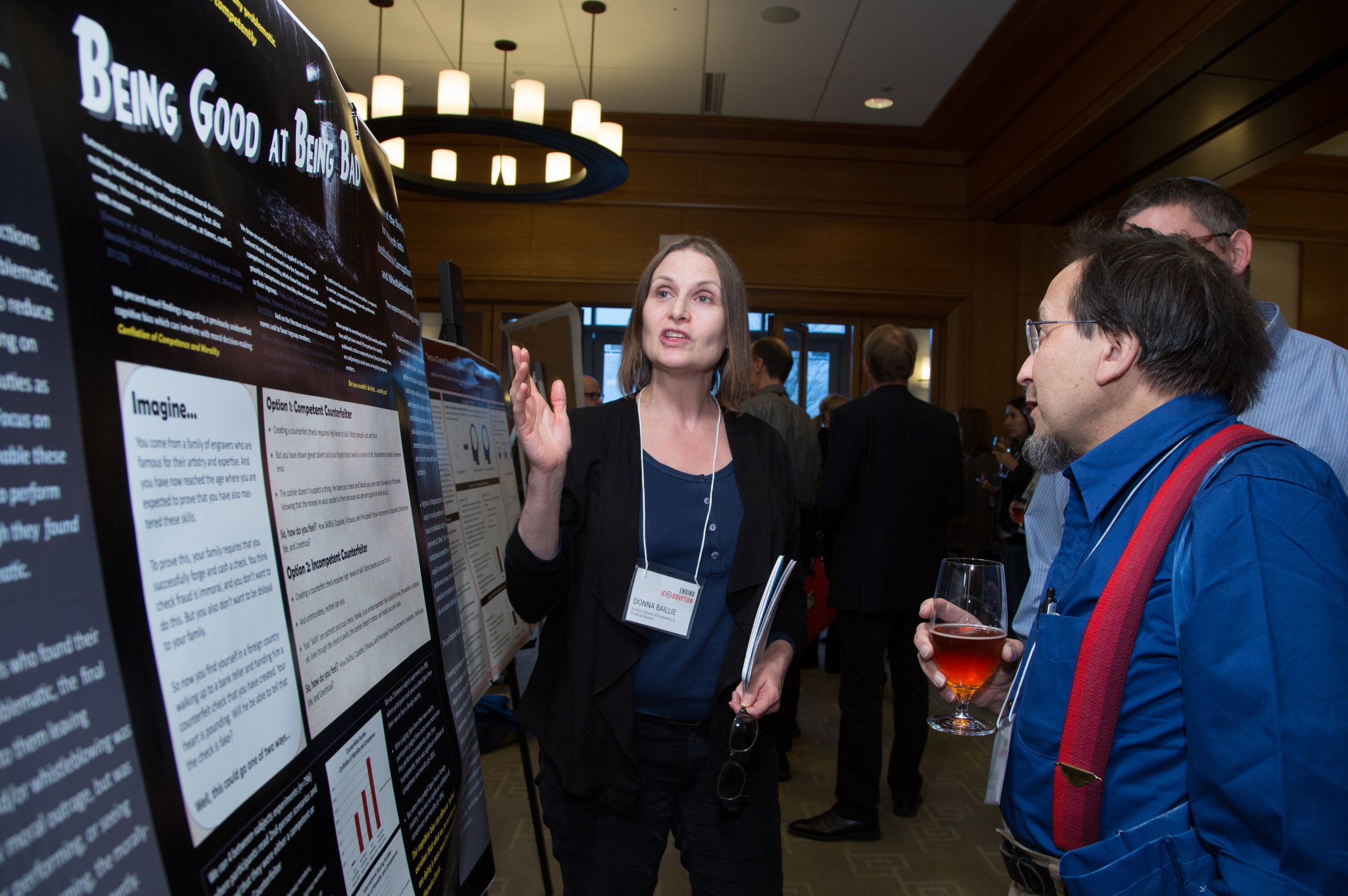

The Edmond J. Safra Research Center Lab on Institutional Corruption marked the end of its five-year existence May 1 and 2 with “Ending Institutional Corruption,” a “celebration” conference focusing on the lab’s accomplishments and featuring presentations by scholars, researchers, and activists.

Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Lessig, the Center’s director and creator of the Lab, referred to the event as a “double entendre of ending institutional corruption and ending the lab. It’s a celebration of an incredibly diverse range of work that has been performed by a great mix of people inside the project over the last five years.”

The conference included panels and workshops that examined the various forms corruption can take and the institutions most beset by it.

The Center’s founding director, Harvard University Professor Dennis F. Thompson, teamed with Lessig in launching the conference with a general discussion, “What Is Institutional Corruption?” Taking the role of interlocutor, Thompson brought up Lessig’s creation last year of the Mayday PAC, whose purpose was to raise money to help candidates committed to campaign-finance reform, and challenged him to defend the concept of changing the system by using the system.

“I am sure that the only way one does it today is using the system to change the system,” Lessig responded. “You can imagine a couple of hundred years ago forming a revolution by people gathering their muskets, marching on the capital, and winning. That was conceivable; people did it. That kind of revolution is not possible anymore because the force, the power on the other side, is just so massive.”

Furthermore, Lessig said, the system contains tools for reform that are accessible to people to use “in a jujitsu-like move to hack the system.”

Former U.S. Congressman Barney Frank ’77 made a similar point on a panel the following day. Citing Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s success in promoting the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2010 and the failure of corporate anti-net-neutrality forces, Frank argued that citizens are not powerless.

“If you don’t convince the average citizen to believe that he or she can make a difference, then nothing else is going to succeed because there will always be people on the other side and those who favor regulation are going to be outvoted every time,” he said.

He also challenged the idea of a “monolithic Washington,” contending that pro-regulation forces are simply outnumbered.

“What’s happened in America recently is that there’s been increasing dominance of people who believe that the public sector has no value,” he said. “The problem is not simply that the regulators are inclined to think the private sector is always right; it is that the political community includes a lot of people who think the public sector is always wrong.”

Trevor Potter, founding president and general counsel of the Campaign Legal Center and former chair of the Federal Election Commission, pointed out that the U.S. Supreme Court also has been playing a large role in determining the limits and boundaries of regulation.

In recent years, he said, the Court has altered its definition of corruption from a broader consideration encompassing appearances of corruption and influence to a narrow concept that sees corruption as “quid pro quo sale of official action.” The Court’s basic position now, he said, is that “gratitude and access are not corrupt in themselves because they are inherent in our system of representative and elective government.”

The problem is not simply that the regulators are inclined to think the private sector is always right; it is that the political community includes a lot of people who think the public sector is always wrong.

Former U.S. Congressman Barney Frank ’77

Panelists also identified private-sector forces that encourage corrupt behavior. Harvard Business School professor Malcolm M. Salter, a senior faculty associate at the Safra Center pointed to “short-termism” as a primary culprit.

“Short termism refers to excessive focus of executives and publicly traded companies along with fund managers and their investors on short-term results,” he said. “The basic hypothesis is: the shorter the time period of measurement, the greater is the incentive for executives to game, to cheat, to pursue personal gains at the expense of their organization’s goals.”

Another common topic was the observation that too many “revolving doors” exist between regulators and industries. Kim Pernell-Gallagher, a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s Sociology Department, argued regulators themselves should be more closely scrutinized.

“We need to pay closer attention to the agendas of the people who design and implement regulation,” she said, “and not just what they’re paid and who they’re dependent on.”

The event drew more than 300 attendees.

***