Adopting the Socratic method—in a hurry

It’s no coincidence that Japan’s new three-year graduate law schools look a lot like the model of legal education Harvard Law School helped craft over the last century.

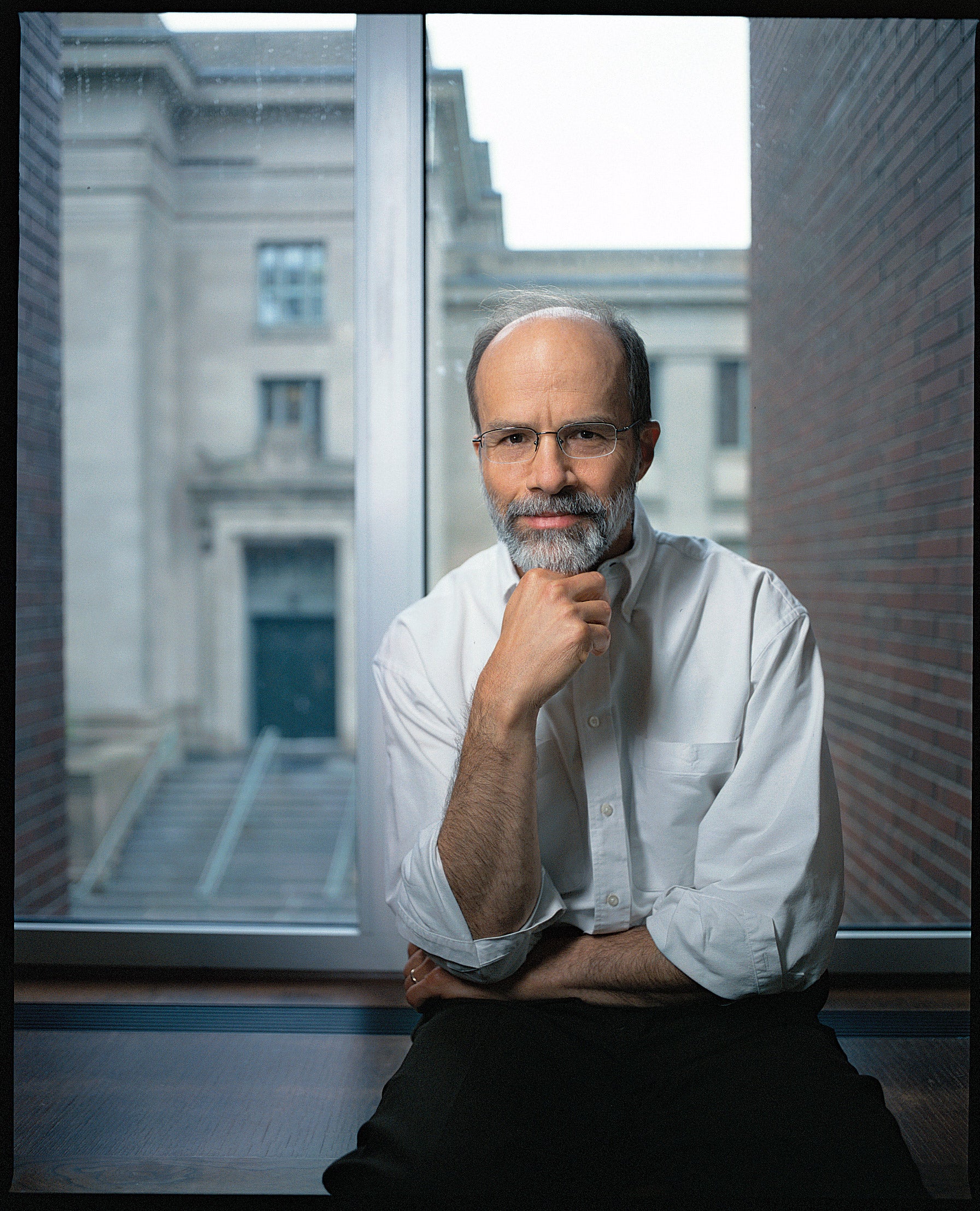

Professor J. Mark Ramseyer ’82 is currently conducting empirical research on the Japanese bar. Like many observers in Japan, he warns that the new law schools will succeed only if a large fraction of their graduates passes the bar exam.

One of the biggest advocates for adopting the new law schools was Yukio Yanagida LL.M. ’66, the founding partner of the Tokyo law firm Yanagida & Nomura.

Yanagida’s experience as a Harvard Law student and later as a visiting professor in 1991 convinced him that Japan should rethink its approach to legal education.

For decades, Japan relied on undergraduate programs to educate its future lawyers. Only a small fraction of students passed the bar exam and advanced into more practical training at the national Legal Training and Research Institute. (Training at the institute, which is run by the judiciary, is a compulsory step between passing the exam and admission to practice.)

In a 1997 lecture at the University of Tokyo, Yanagida argued that Japanese law students—and the profession as a whole—would benefit from more diverse academic experiences prior to the study of law. Japanese law schools should follow Harvard’s model of providing “the training and education required for becoming an effective legal practitioner” and teaching students to “think like a lawyer,” he said.

The vision he laid out in that speech won a big endorsement in 2001, when the government-appointed Justice System Reform Council called for creating three-year graduate schools in law, U.S.-style. And his vision came to fruition in 2004, when the first of 68 such schools began to open their doors.

Setting up so many law schools so quickly required plenty of intense planning. Professors had to adapt the Socratic method to a civil law system with a much lower volume of cases, for students accustomed to learning more passively from lectures.

Helping this transition was another Harvard Law alumnus, University of Tokyo Professor Daniel H. Foote ’81, who was the sole non-Japan native involved in the planning committees that helped create the new schools.

Foote says his suggestions “were accorded more weight” whenever he referred to the experience of Harvard Law School. For example, when planners tried determining the ideal class size, Foote pointed to HLS’s decision to reduce first-year class size to 80 students. “After I mentioned the HLS reform, consensus quickly developed at the 80-student level,” he said.

Not surprisingly, though, such a rapid debut for the new law schools has not been glitch-free.

“Not all law schools are prepared … [or] well-organized,” said Masakazu Iwakura LL.M. ’93 of Nishimura & Partners. “Complaints are increasing among the law students.”

Students were particularly disappointed to learn that the bar pass rate will be far lower than the 70 or 80 percent level envisioned by the Justice System Reform Council.

“Once students realize that they pay for this for two or three years and then flunk the bar anyway, they’re not going to have any interest in doing this,” said HLS Professor J. Mark Ramseyer ’82. “Some of the lower-ranking schools are going to have to close down.”