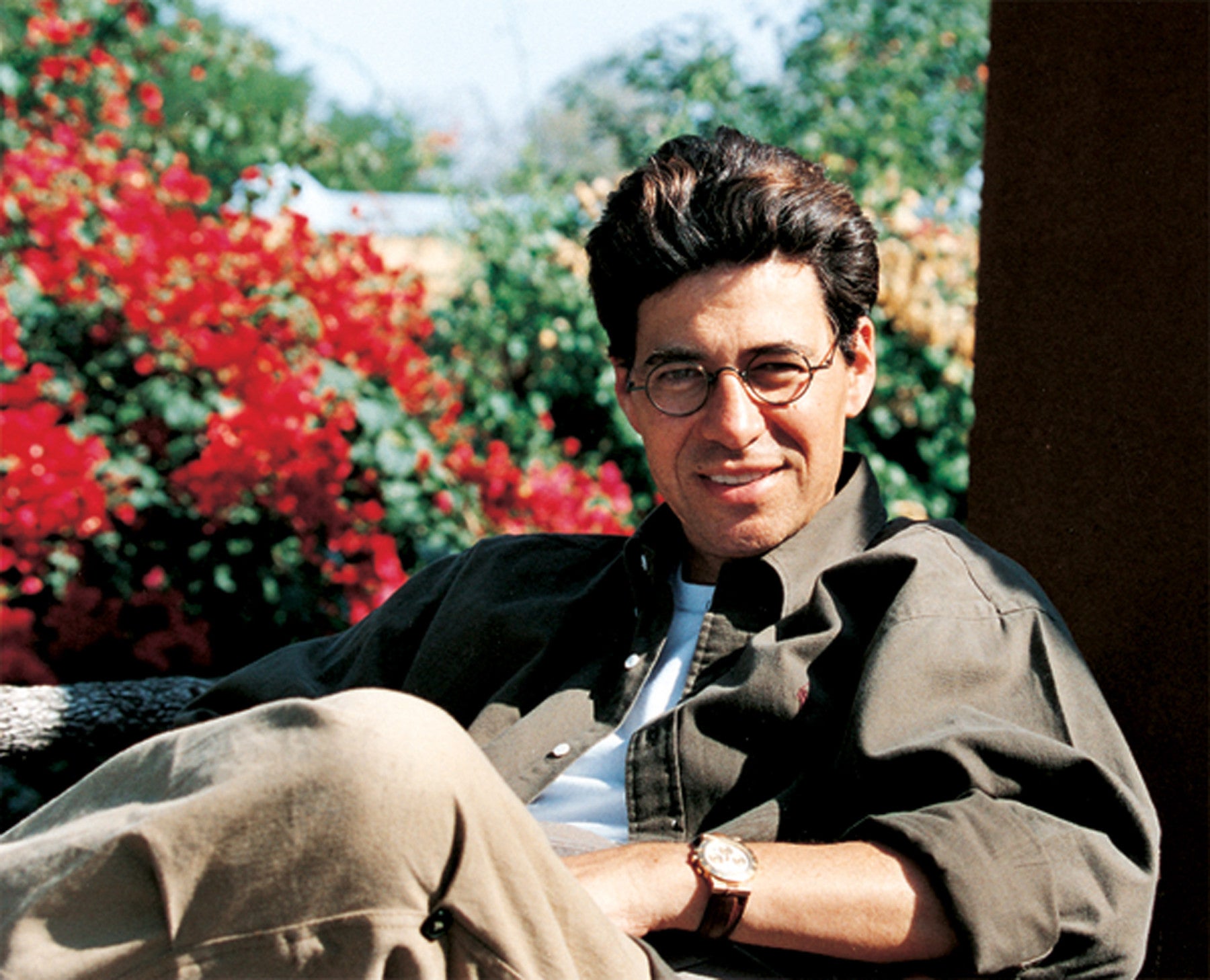

Wildlife photographer Bobby Haas ’72 has discovered a place and a passion that have changed his view of the world.

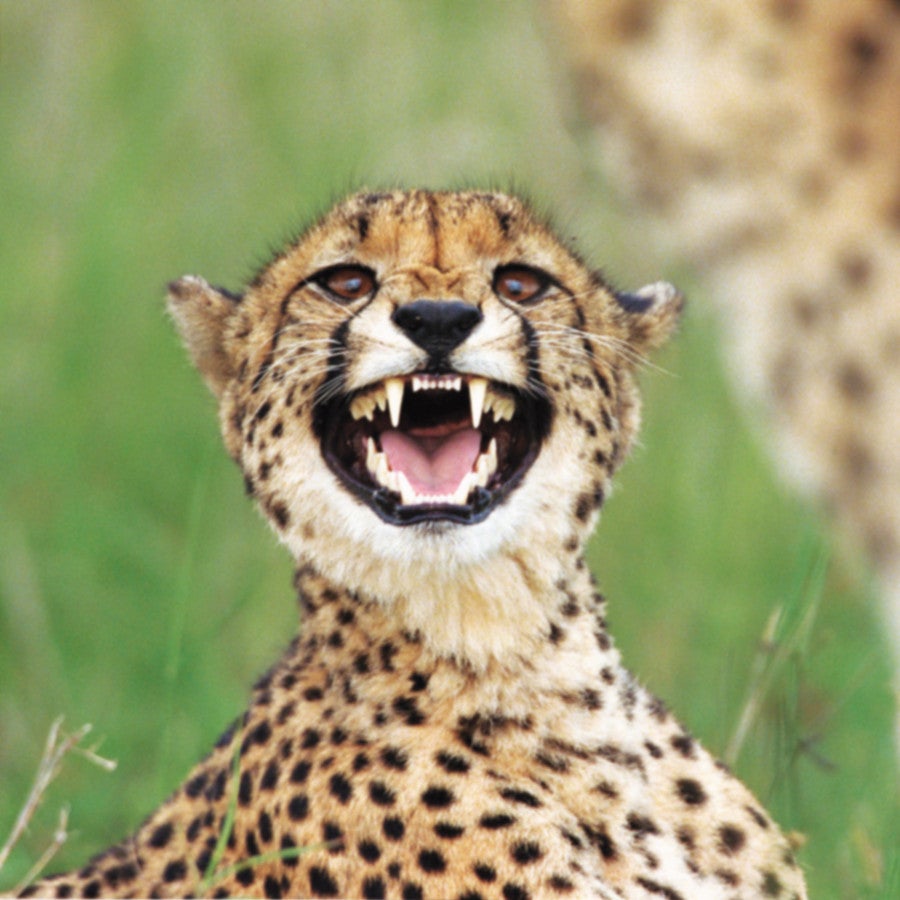

Crouched a few hundred yards from the Land Cruiser, Bobby Haas ’72 viewed the two cheetahs eye-to-eye through the camera lens as they stalked him. Undeterred as the gap between them narrowed, he clicked away, instinctively guarding his face with his hand as a lawn mower-like noise grew louder in the African savannah air. It was only purring. The first cheetah rubbed slowly but firmly against Haas’s side. The second followed, resting its face only inches from Haas’s before moving on. His daughter watched in “slack-jawed amazement. She told me I was crazy,” wrote Haas in his journal from Lewa Downs, Kenya. Haas said he later learned that the two brothers had been raised in captivity and then released into the wild–a dangerous combination. “It was a defining moment. We walked away with a part of Africa deeply embedded in our psyche.”

The need for a break from the intense life of an investor was what first prompted Haas to act on the suggestion of a colleague from Goldman Sachs to try a photographic safari on a Kenyan game preserve in 1994. Within 24 hours he became mesmerized by the mystique of Africa and its wildlife. “There was a feeling I had the very first night in Africa under the stars in a tent with an army blanket and a metal cot,” he said. “I felt a sense of belonging, a sense of being at peace.”

Since 1984 Haas has been in the fast lane of the investment world, specializing in buyouts and acquisitions. In 1992 he founded Haas Wheat & Partners, a Dallas-based private investment firm. Together with its predecessors, the firm has completed in excess of $7 billion in buyout transactions. It is a world he simply forgets, however, when he goes to Africa.

Over the past eight years Haas has journeyed throughout Kenya, South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia on more than a dozen safaris. He travels with an assortment of cameras and lenses, most often working with his mentor, Richard du Toit, a renowned wildlife photographer. Like du Toit, he hasn’t had any formal photographic training. “There is no substitute for working in the field, taking thousands and thousands of photos,” said Haas. He and du Toit work long hours, often rising at 4 a.m. to catch the first light and remaining in the field until after sundown.

Patience and persistence are the keys to getting the shots. “We might see a cheetah lying on a termite mound but notice that he is particularly lean,” said Haas. “So we might stay with the cheetah for six or seven hours on the belief that he is going to hunt soon. . . . We would see [cheetahs] fight, we would see them try to mate, and we would see them play.

“When we are out there, we are at the office, if you will. We are, in some sense of the word, working–working on a passion,” he said. Haas estimates that on a 10-day trip last fall on the Chobe River, he took 300 rolls of film, or 10,000 images.

Haas has now published two books: A Vision of Africa, winner of the Katie award for literary and photographic excellence, and most recently Predators, which was launched at a fund-raiser for the Cheetah Conservation Fund in the fall. He is working on his first children’s book, African Critters, a photographic journal that will be published in July, and a fourth book that was prompted by the terrorist attacks of September 11.

Haas was in the remote regions of Botswana when he learned via shortwave radio of the attacks. “During the day I was out photographing scenes that have gone on for 20- to 30-million years, and at night I wrote in my journal about war, death, and terrorism,” he said. Haas decided upon his return to share his thoughts and photos from that unique period in another book. “You are faced with life and death every day in the wilderness. Animals deal with it differently.”

“I really think that Africa has helped me to sharpen and to simplify my own thinking about life and death and the world and what kind of contribution I can make,” said Haas. “My contribution has to be much greater than aggregating capital. There is nothing wrong with that, but it has to be greater than that.”

Haas’s books are not available commercially. He publishes the high-quality editions to raise money for organizations dedicated to the preservation of endangered species, including the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Namibia, the WILD Foundation, the International Exotic Feline Foundation, and Fossil Rim. He says it is his small way of giving something back.