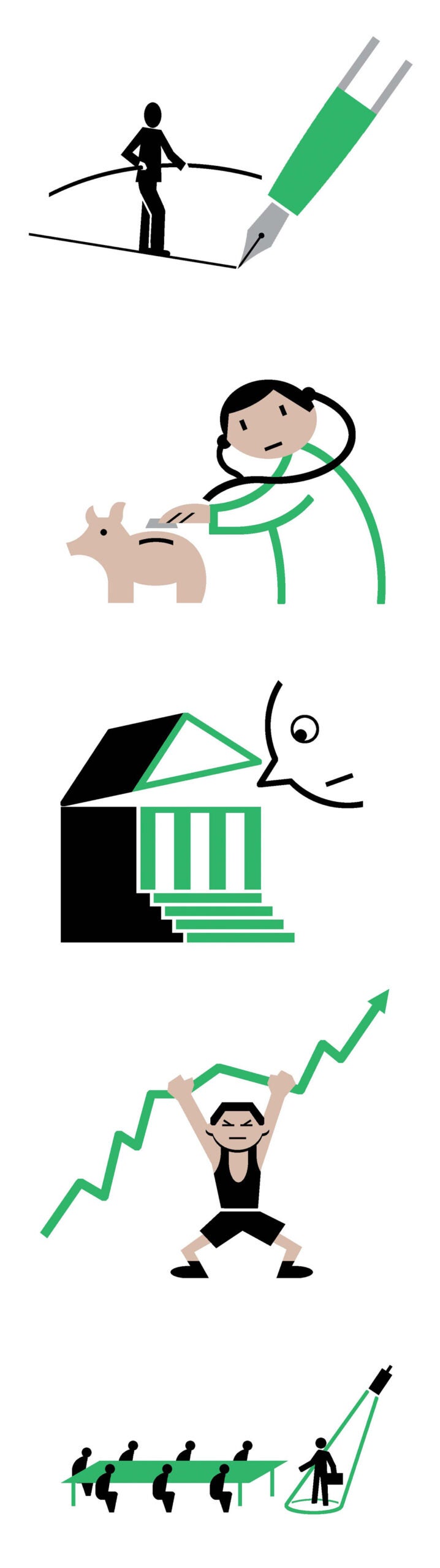

General accountability principles, from some leading experts

As the global economy continues to reel, the key question is how to prevent a crash from happening again. Accountability is key, experts agree, and HLS faculty have been quoted daily in newspapers and online over the past few months on how to keep the economy out of trouble in the future. What reforms are needed to ensure that this doesn’t happen again? The Bulletin asked that question of HLS faculty deeply involved in understanding and solving the crisis.

Professor Lucian Bebchuk LL.M. ’80 S.J.D. ’84, director, HLS Program on Corporate Governance:

Two areas that call for reforms are executive compensation and shareholder rights. In our 2004 book, “Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation,” Jesse Fried and I analyzed how executive compensation practices distort the incentives of executives. Recent events have highlighted how costly such distortions can be. Compensation arrangements should be structured carefully to provide executives with strong incentives to maximize long-term shareholder value and avoid the taking of excessive risks.

In addition, we should seek to make boards more accountable to shareholders. To this end, directors should be not only independent of management but also dependent on shareholders. To this end, shareholder rights should be strengthened: Corporate arrangements should facilitate shareholders’ ability to replace directors and to shape the governance arrangements regulating their firms.

Note: Jesse Fried ’92 will join the HLS faculty in the fall as a professor of law, coming from the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law.

Professor Howell Jackson ’82, acting dean of HLS:

We need regulatory reform to modernize the oversight of the financial industry to reflect the reality that financial risk is generated in many different parts of the economy now. The regulatory structure needs to be consolidated and given expanded jurisdiction to monitor those risks and intervene effectively when problems arise. That means discarding the traditional sectors of banking, securities and insurance; giving broad oversight powers to a consolidated agency; and reserving the Federal Reserve Board’s jurisdiction to policies that focus on systemic risk. And consumer financial protection has got to be the subject of a specific organization rather than having that responsibility divided up into many different parts of the federal supervisory apparatus. This is a substantial challenge that may take several years to fully implement, but now is the time we need to start down that path to develop a framework that will result in a modern regulatory structure. I do think it can be done.

Professor Hal S. Scott, director, HLS Program on International Financial Systems:

There is clearly a need going forward to get more accountability in the system. This requires dealing with the immense moral hazard we have created by bailing out shareholders and debt holders in a wide number of institutions, to avoid systemic risk. Over 300 institutions have received TARP funds, so this problem is not limited to the biggest or more important institutions. Once large institutions get help, small banks and their representatives demand equal treatment. We need to reduce the possibilities of systemic risk by a variety of measures, such as tougher and better capital standards (including more market discipline based on better disclosure), and a requirement that derivatives be centrally cleared and in some instances listed on an exchange. We also need a receivership process to handle nonbanks and all financial service holding companies.

Professor Martha Minow, co-editor of the recent book “Government by Contract: Outsourcing and American Democracy”:

Government agencies have lacked personnel and expert capacity to keep up with the wizardry of financial markets, and conflicts of interests have hobbled oversight by credit-rating agencies, government agencies and Congress. So at a minimum, governments must demand the information needed to monitor the total risks undertaken at any financial institution; and government agencies must obtain capacities to regulate the entire range of investment activities. Rating agencies shouldn’t get compensated by the firms whose products they rate nor should they advise firms how to create the very same products that the agencies rate. And even the stimulus package must include sufficient resources to enable effective government oversight of funds spent.

Professor Charles Fried, who teaches contracts and constitutional law, on the A.I.G. bonus scandal:

Faithful performance of contractual obligations is certainly a keystone of a well-functioning system of business and credit—especially where the alternative to performance, paying damages, is no alternative at all since the performance and the damages are the same. But that surely does not mean the money should have been paid out no matter what. Could the well-known doctrine of change in underlying assumptions have been invoked to abrogate the obligation? Since the alternative to the government bailout would have been bankruptcy with a resulting abrogation of these bonus promises along with other contractual obligations, was management remiss in not pressing for a renegotiation, and were any of the recipients themselves involved in a self-dealing way in deciding not to renegotiate? And most pertinently, as these bonuses appear to have been related to performance of services, is it clear that the recipients faithfully performed the services for which they were being compensated? These and other such questions cannot be answered without seeing the actual contracts that are being invoked. And even then, there are questions about whether the performance of these individuals matched the performance set out in the contracts. As we all own 80 percent of the company, we ought to be able to see the text of these contracts. They should be posted on our company’s — that is, A.I.G.’s — Web site. Then we can discuss whether the recipients of that money really earned it. [This text first appeared on The New York Times Blog, March 17, 2009.]