Affirmative action remains contested terrain even among its proponents, as was evident in a debate between two Harvard Law School faculty members in the fall.

Sponsored by Harvard’s Civil Rights Project, whose mission is “to help renew the civil rights movement by bridging the worlds of ideas and action,” the event took place poolside at the swank Beverly Hills Tennis Club and was moderated by Bert Fields ’52, a prominent Los Angeles entertainment attorney whose clients include Steven Spielberg, Tom Cruise and Warren Beatty.

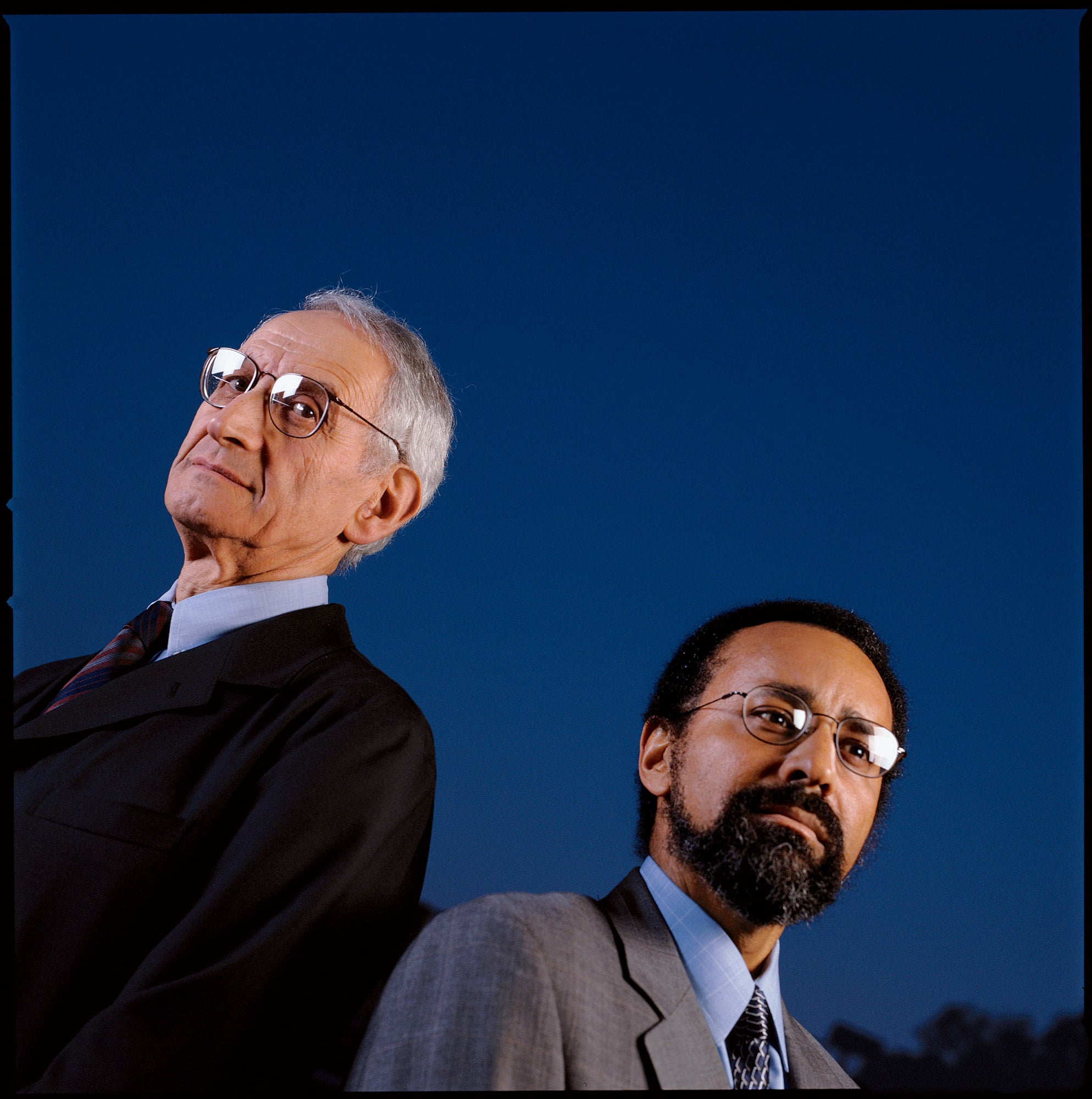

Before an audience of about 30 people, Fields opened the discussion by saying that when he entered HLS, the school had two African-American students, no Latinos and no women. Today, Harvard Law School is a far more integrated institution, but judging by the lively exchange between Professor Charles Fried, who served as U.S. solicitor general in the Reagan administration, and Professor Christopher Edley Jr. ‘ 78, an adviser on race to the Clinton administration and co-founder of the Civil Rights Project, affirmative action still has a role to play both at the school (which was the scene of racial incidents in 2002) and beyond.

Fried raised “two cheers” for affirmative action, arguing that without minorities in positions of prominence, “we are two people, not one.” The purpose of affirmative action in elite institutions, Fried said, is to create visible minorities, so that white students would see the black students among them as equals, not as different people. But, he added, once that goal is achieved, affirmative action should be dismantled “with all deliberate speed,” in part because rising rates of intermarriage will soon make it difficult to decide who is a minority, but also because the more we segment ourselves by race, the more groups other than African-Americans will feel entitled to special treatment.

“If we go on too long, too many people will be making a living out of affirmative action,” he said, citing the Rev. Al Sharpton as a case in point. “And they won’t let us stop.”

Edley, whose father, Christopher Edley Sr. ’53, was one of the school’s early African-American students, conceded that affirmative action has its costs, notably in white backlash, as reflected in the recent dispute over whether race should be a factor in the University of Michigan Law School’s admissions policy. Nevertheless, he defended race-based decision-making as an essential, if limited, tool in “the transition from apartheid to a fully integrated community” and argued that this is likely to take longer than the 25 years predicted by Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Affirmative action, he noted, furthers the excellence of institutions by making them reflect the diversity of the population at large.

An audience member raised the thorny issue of the role of racial quotas in a meritocracy that is also committed to diversity. Fried opposed quotas outright, while Edley, acknowledging that quotas are “rigid numerical straitjackets” that privilege race over other factors, nonetheless felt that the notion of merit should include the attributes a candidate will bring to a community. Following the discussion, Randy Bassett ’69 commented that the word “quota” itself has negative connotations. “For that reason,” he said, “it can’t be advocated. The mind shuts down.”