Does the First Amendment shield major media organizations from responsibility for demonstrably false and possibly harmful statements made on their airwaves? That is the central question in a defamation lawsuit filed by a previously obscure election technology company against Fox News and allies of former President Donald Trump.

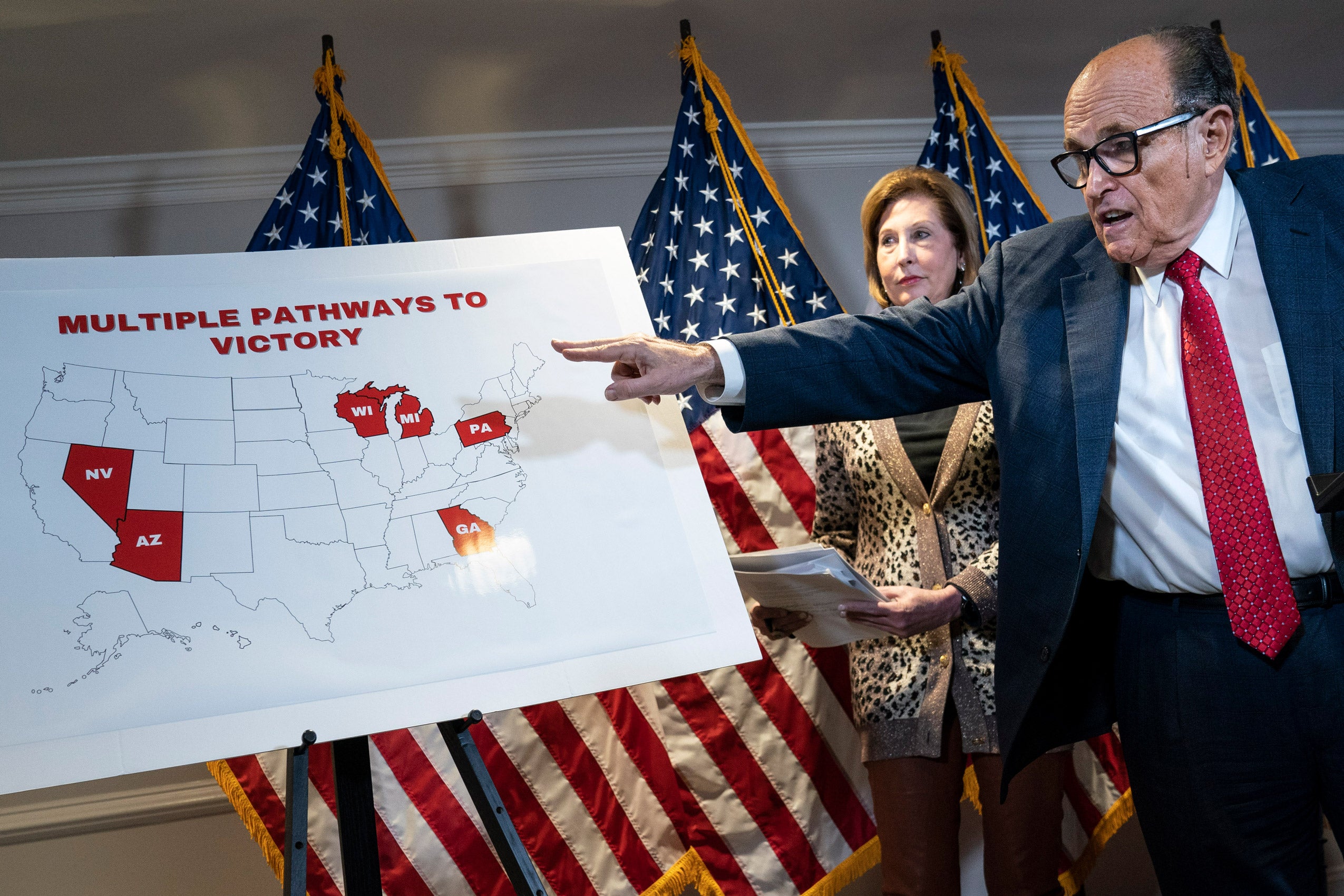

On February 4, Smartmatic, whose technology was used in Los Angeles during the 2020 election, sued Fox, anchors Lou Dobbs, Maria Bartiromo, and Jeanine Pirro, and the former president’s representatives Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell. The company’s complaint alleges that Fox “joined the conspiracy to defame and disparage Smartmatic and its election technology and software…” as part of a broader “disinformation campaign” designed to sow doubt about the election’s results. This followed similar defamation lawsuits filed against Giuliani and Powell by Dominion Voting Systems in January. In recent weeks, Fox has canceled Dobbs’ show and asked the judge to dismiss the suit, claiming First Amendment protection, arguing: “An attempt by a sitting president to challenge the result of an election is objectively newsworthy.” Dominion has also indicated plans to sue MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell for promoting baseless election fraud claims.

In an email Q&A with Harvard Law Today, tort law expert and Harvard Law School Professor John C.P. Goldberg explains what the companies must do to prove their claims, how likely they are to succeed, and whether these types of lawsuits might have an impact in the fight against disinformation.

Harvard Law Today: How strong are the cases being made by Dominion and Smartmatic?

John Goldberg: As you note, the two companies have brought defamation suits against multiple defendants. Based on the allegations contained in their complaints — allegations that of course have yet to be proven in court — most or all of their claims seem plausible, and some seem compelling. However, different defendants may have more success fighting liability. A news operation such as Fox, for example, will argue that the law needs to give it leeway to provide airtime to headline-makers such as Giuliani, even if there’s some chance that they will say false and defamatory things during a broadcast.

HLT: What is the definition of defamation and what does one need to prove it?

Goldberg: Defamation comes in two forms: libel (roughly, written or broadcast defamation) and slander (roughly, spoken defamation). Under the Supreme Court’s famous 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan decision, as well as subsequent decisions, what a libel plaintiff has to prove varies depending on whether the plaintiff is a “public figure” or a “private figure.” Courts usually treat household-name companies such as Amazon as public figures. But it is less clear whether lesser-known companies, like these voting-machine companies, which really have only come to public attention as a result of the very statements that they allege to be defamatory, will be deemed public figures.

Professor John C.P. Goldberg

Assuming these companies are deemed public figures, then for either of them to recover damages from any of the defendants, it will have to prove that the defendant made a statement about the company that was false, and that is the sort of statement that tends to harm a business’s reputation. It will also have to show that the defendant made the statement with “actual malice”: that is, while actually knowing the statement to be false, or with reckless disregard as to its falsity. Usually for a public-figure plaintiff, the hard part of a libel case is proving actual malice, but the allegations in these lawsuits suggest that at least some of the defendants may well have knowingly or recklessly made false statements.

HLT: What defenses do you expect from Fox and from Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell?

Goldberg: Again, assuming the plaintiffs are deemed public figures, all of the defendants will argue that, even if they perhaps could have been more diligent in checking to make sure they didn’t say false things, they did not act with actual malice. In addition, as I mention above (and will return to below), the networks will argue that giving airtime to a guest speaker is not a ground for holding them responsible, even if the speaker him or herself is responsible.

HLT: Fox recently canceled Lou Dobbs Tonight. Will this type of retrospective action help their legal case?

Goldberg: Firing a presenter such as Lou Dobbs won’t protect Fox from liability for any defamatory statements he made on his show before being fired. However, it can help Fox in other ways. If they were worried about Dobbs continuing to make disparaging statements about the companies then obviously they avoid that risk by not having him appear on air anymore. It’s also possible that this move is part of an effort by Fox to convey that they are generally behaving responsibly. This could be important because a defendant that behaves with a shocking degree of irresponsibility might find itself paying a successful libel plaintiff not only compensatory damages but also punitive damages. So, firing Dobbs might be a way for Fox to signal that it is, in general, a responsible operation and hence should not be subject to punitive damages even if ends up being held liable for compensatory damages.

HLT: We talk a lot about regulating speech on social media, but a lot less about regulating speech at news outlets. To what degree is a media company like Fox News or, say, the New York Times, responsible for content they broadcast or post, either from their own employees — anchors, reporters, and opinion show hosts — or from guests?

Goldberg: There’s a very old and important rule of defamation law known as the “republication rule.” In a nutshell, the republication rule says that someone who repeats another person’s defamatory statement is just as responsible as the originator of the statement. Repetition is how defamatory remarks do their damage, and so the law is designed to discourage repetition and hold people responsible for it. The republication rule has long provided the basis for holding outlets such as the New York Times or Fox News liable when they print or broadcast other people’s defamatory statements. Indeed, in the famous Sullivan case itself, the defamatory statements at the heart of the lawsuit were not made by an employee of the New York Times, but instead appeared in a paid political advertisement that was run in an issue of the paper.

Although “republication” is thus the baseline legal rule, it has a number of qualifications and exceptions. I mentioned above that a network such as Fox News is likely to argue that it is entitled to leeway to broadcast segments featuring guests who might make controversial and even defamatory statements. This, in essence, would be an argument for an exception to the republication rule based on the importance of the public being able to hear from persons involved in political controversies as the controversies are unfolding.

HLT: Will these defamation lawsuits likely have any long-term impact on the credibility of information being shared on TV or online? Do they represent a useful tool for holding people or companies that spread misinformation accountable? Or is there a better way to accomplish that goal?

Goldberg: It’s always hazardous to predict how particular lawsuits might change things, in part because we don’t know how they are going to play out. If, for example, some of the defendants are able to resolve these suits with a relatively modest settlement payment and no admission of guilt, then the message might be to other speakers and broadcasters “Don’t worry too much about defamation law.”

On the other hand, as is perhaps evidenced by actions such as the firing of Lou Dobbs, it may be that these suits are reminding speakers and news sources that, even under Sullivan — which has helped to make the U.S. an outlier among industrialized nations in terms of its willingness to tolerate more defamation in exchange for more robust free speech — there are some legal lines that cannot be crossed. It does seem like 2021 is a moment in which, for the first time since Sullivan, a powerful political coalition is forming that will favor cutting back on existing First Amendment protections against defamation liability. Both President Trump, who claims to be constantly maligned by the media, and progressive critics outraged over unfounded allegations of election fraud, are calling for Congress and the courts to adjust the balance in a way that makes it easier to recover damages for defamation and thus riskier to write or broadcast nasty things about people or companies.