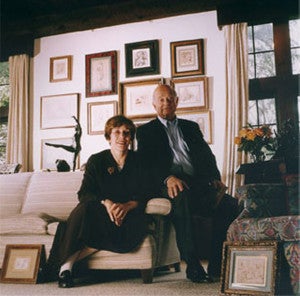

This past June, the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard received an extraordinary gift of 110 seventeenth-century Dutch drawings from the collection of George and Maida Abrams. The news attracted international attention — the Abramses own the finest private collection in this field and one of the foremost in the world, which they have assiduously built and refined since the 1960s.

Thanks to the Abramses, the Fogg now houses the foremost collection of Dutch drawings in the country, enriching the museum’s mission of research, professional training, and programming in a manner that “has happened only a few times in our history,” said James Cuno, director of the Harvard University Art Museums. The peerless gift offers a sweeping view of masterworks and rare drawings by Dutch and Flemish artists from the mid-1500s to 1700, among them Rembrandt, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Hendrick Goltzius, Adriaen van Ostade, Jacques de Gheyn II, Cornelis Vroom, Jacob van Ruisdael, and many others. The gift also chronicles the major styles and genres of this remarkably prolific period.

“Maida and I have always been committed to making our collection available to scholars and students by welcoming them into our home and lending works to institutions across the United States and Europe,” George Abrams said in announcing their gift. “We want to continue to encourage future generations of scholars and, through them, spark the interest of the public in appreciating Dutch drawings and art. We can think of no better way to continue the tradition of sharing these magical works than to give them a permanent home at the Fogg Art Museum.”

The Abramses are internationally known collectors, respected for their wisdom, vision, and tenacity. George Abrams ’57 is also a Harvard-trained lawyer who has built an independent, high-powered practice. The inspiration for Abrams’ double life in art and law hearkens back to his early HLS days.

During his first year at the School, Abrams made an unusual choice. Rather than spend his summers working at a law firm, the traditional route for 1Ls and 2Ls, Abrams took a job planning cultural activities for students abroad, for a Dutch organization that ran exchange programs.

“So instead of doing what I was supposed to do, learning more about the law, I spent my summers in Holland, where I devoted as much time as I could [to visiting museums]. I grew to love the art of that country,” he says.

As a Harvard College student Abrams had taken some art history courses, and as managing editor of the Harvard Crimson he regularly reported exhibition openings at the Fogg Art Museum. But it was during his Holland summers that this general inclination toward the arts began to sharpen and focus. All the while he diligently flourished in law school, Abrams was chafing at “the full-time focus on the law, to the exclusion of other interests.”

A member of the Army Reserve, Abrams went on active duty for six months after graduation, which interrupted his “immersion in law.” Returning to civilian life he went into practice with his father, Samuel (’26), and his sister Ruth Abrams ’56, who would later become an assistant DA, assistant attorney general, and the first woman to serve on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

Abrams found legal practice was, after all, to his liking. Yet he knew he wanted a life involved in the arts as much as a life in the law, and he gained an ideal partner in that quest in 1960, when he married Maida Stocker, a philosophy and arts major at Sarah Lawrence College.

One of George Abrams’ first law clients, a Boston art dealer named Hyman Swetzoff, shared his interest in old master drawings with the young couple, and encouraged them to begin their own collection. The Abramses admired the intimacy and humanity of the delicate works. As George Abrams later wrote: “We loved holding drawings in our hands and looking carefully at those markings in pen and ink, charcoal, gouache, and silverpoint. To see and sometimes possess works by artists who lived and worked 300 or 400 years ago seemed like a miracle. The finest drawings appeared to exist on two levels, the one material, the other spiritual, a peculiar unity between the expression of something eternal and the fragile being of a small piece of paper.”

When they first started collecting, the Abramses lived on the bottom floor of a Commonwealth Avenue brownstone in Boston and had limited financial resources. Drawings were a more affordable medium for the novice collectors. As for choosing a specialty, they settled easily on seventeenth-century Dutch drawings. George was already an aficionado of Dutch art, and both were drawn to the naturalism and immediacy of drawings from this period. The Twelve Years’ Truce of 1609 ushered in a tranquil, prosperous era, during which Dutch artists turned away from traditional religious subjects to find their inspiration in the richness of ordinary life. They produced a cornucopia of imagery: views of wooded landscapes and calm seas, gypsy subjects, scenes of “low life” and “high life,” delicate portraits, tulip and insect studies, architectural interiors, and much more.

While George Abrams the collector was pursuing his personal interests in the arts, George Abrams the attorney continued to uphold the family legal tradition. In practice with his sister and father, Abrams enjoyed the extensive trial work that came his way. The Abrams, Abrams & Abrams “shingle” from this era now hangs in his office at Hale and Dorr.

Then in 1965 Abrams accepted a job offer from his Harvard College classmate Ted Kennedy, to become general counsel and staff director of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Refugees, which he ran for three years. It was the height of the Vietnam War, and the committee hearings Abrams helped organize addressed the politically risky topic of Vietnamese refugees and civilian casualties. “Things had clearly gone awry in Vietnam. It was a no-win situation. Public opinion began to change, and looking back I can at least feel we were raising the right questions” in the hearings, Abrams says. He also traveled in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and elsewhere in the Middle East, where he visited refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza Strip both before and after the ’67 war.

In 1968 he joined Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign. His government service ended abruptly, when he returned to Boston after the assassinated senator’s burial. With no heart for remaining in Washington, Abrams began practicing law again, first with his own small firm, which gave him the freedom to develop a loyal group of clients while fitting in as much collecting as possible. He enjoys that same flexibility in his current association with Hale and Dorr.

The independent lawyer’s longtime clients include HLS professors and two other men known for blazing their own trails: Dr. Judah Folkman, the scientist whose research is attracting intense international attention, and Sumner Redstone ’47. Abrams has represented Redstone, now head of the Viacom media company, since the 1960s. He was deeply involved in Redstone’s takeover of Viacom and subsequently in the Paramount takeover battle, among other massive transactions, and has been on Viacom’s ten-member board of directors since 1986.

His work for another client, Sonesta International Hotels, allowed Abrams to neatly combine lawyering and collecting. He was charged with developing a major hotel complex in Amsterdam for Sonesta, which entailed spending a week a month in that city for most of the 1970s into the 1980s — putting Abrams in the right place, often at the right time, to pursue the drawings he and Maida wanted.

While Abrams has tracked some drawings on his own, typically he and his wife have ventured forth together on countless treks through Europe and other countries. “It was an all-consuming interest from the very start,” Abrams recalls, “yet we’ve always loved our collecting experiences, even under the most difficult circumstances.”

Collecting old master drawings poses many challenges, he explains. For one thing, the works are often unsigned. “The collector has to rely on extensive knowledge and experience to determine the artist’s identity. The risks of being misled or making mistakes are enormous” — and the Abramses experienced both early on. They were fast learners, however, willing to take risks, and eager to learn from others. They also enjoyed a fleeting advantage by starting out when seventeenth-century Dutch art was not in fashion. “We had a clear field for 10 to 15 years and had marvelous opportunities that can never be repeated.”

From the beginning, Abrams continues, “Maida and I have insisted that we agree on any drawing we buy, and only choose works we really want to look at and live with. That approach meant we often purchased works by artists we liked who were less known then, many of whom are much better known now. It has also allowed us to put together large groups of artists who have become very important today.”

According to Abrams, he applies his lawyer’s training to studying and analyzing information about their field, and his wife offers incisive judgments about individual works drawing upon her training in the arts. Sometimes, he admits, “I become so fascinated with the background and rarity of an artist that Maida has to step in and get me back on track.” Both are dedicated students of their field, and their Dutch art library, in constant use, has grown from a few hundred books and catalogues to more than 7,000 volumes today.

In addition to the Fogg, the Abramses have loaned and given works to leading museums throughout the world. Their drawings have been represented in many major exhibitions, including the critically acclaimed, hugely popular Seventeenth-Century Dutch Drawings: A Selection from the Maida and George Abrams Collection, which opened at the Rijksmuseum in 1991, and traveled to the Albertina in Vienna, and then to the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, before reaching the Fogg in 1992.

Parting with the works of art one loves is the hardest thing a collector can do, Abrams says, “but it was time. We want others to enjoy the special magic of our drawings.” And so he and Maida have entrusted to the Fogg and Harvard many of their hard-won treasures, including two “standing figures of dandies” by Willem Buytewech; the famous A Farm on the Amsteldijk by Rembrandt; a “friendship album” consisting of 41 drawings produced by at least 28 different artists, including the only known drawing by Emanuel de Witte, famed for his paintings of church interiors; Gerbrand van den Eeckhout’s lovely A Woman Doing Handwork; and dozens more, each telling a tale of the collectors’ taste and aspirations.

Harvard has given an old friend of the Abramses’, Fogg curator William Robinson, a new title in recognition of their gift: The Maida and George Abrams Curator of Drawings. Robinson is a specialist in Dutch work in part because of the Abramses’ example. While a Harvard graduate student in the ’70s, Robinson became interested in seventeenth-century Dutch painting. “People told me, ‘There are collectors of drawings in the neighborhood. You ought to go meet them.’” Eventually he made his way to the Abrams home. “I quickly realized their private collection held works by artists I knew weren’t represented in any museum collection in this country, and concentrations of important drawings like nothing I had ever encountered.”

Robinson began spending a lot of time with the Abramses and their collection, and eventually organized the 1991–92 exhibition. Maida Abrams, he observes, “prefers to stay in the background, but her views are extremely important. George will weigh all sides of a question, and her opinion will be the decisive factor.” As for George Abrams, “he is one of the most dedicated and committed collectors I’ve ever met. I do think, if you ask George, that his collecting may take priority over his law work.”

The Abramses have not stopped collecting, nor has their generous gift to the Fogg left empty spaces on their walls. Their private collection still numbers in the many hundreds of paintings and drawings. They will continue the pilgrimages they delight in, to the great Dutch collections and major auction houses, to the offices and homes of the leading dealers, curators, and scholars. Maida still heads up the nonprofit Very Special Arts, as she has for 25 years, which organizes local and national programs for special-needs individuals. And George is serving his 30th year on the visiting committee of the Harvard Art Museums. He is also a trustee of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, a fellow of the Morgan Library, and a member of the prestigious vetting committee for the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, the Netherlands.

These days, the drawings they seek are harder to come by, says George Abrams. Thanks in no small measure to him and to Maida, Dutch seventeenth-century art has grown extremely popular, and even these two well-connected, savvy collectors face enormous competition. Still, the pleasures of the quest are as strong as ever.

In a career that has encompassed “the political, business, legal, and art worlds,” Abrams notes, “the last may be the most important to me. What I find most exciting is studying old master drawings, working on attributions, finding new information, learning new things.” Yet despite the fact that his law practice demands much of his attention, limiting his time for art sleuthing and exploration, Abrams says, “I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

All artwork from Fogg Art Museum, The Maida and George Abrams Art Collection, Promised Gift