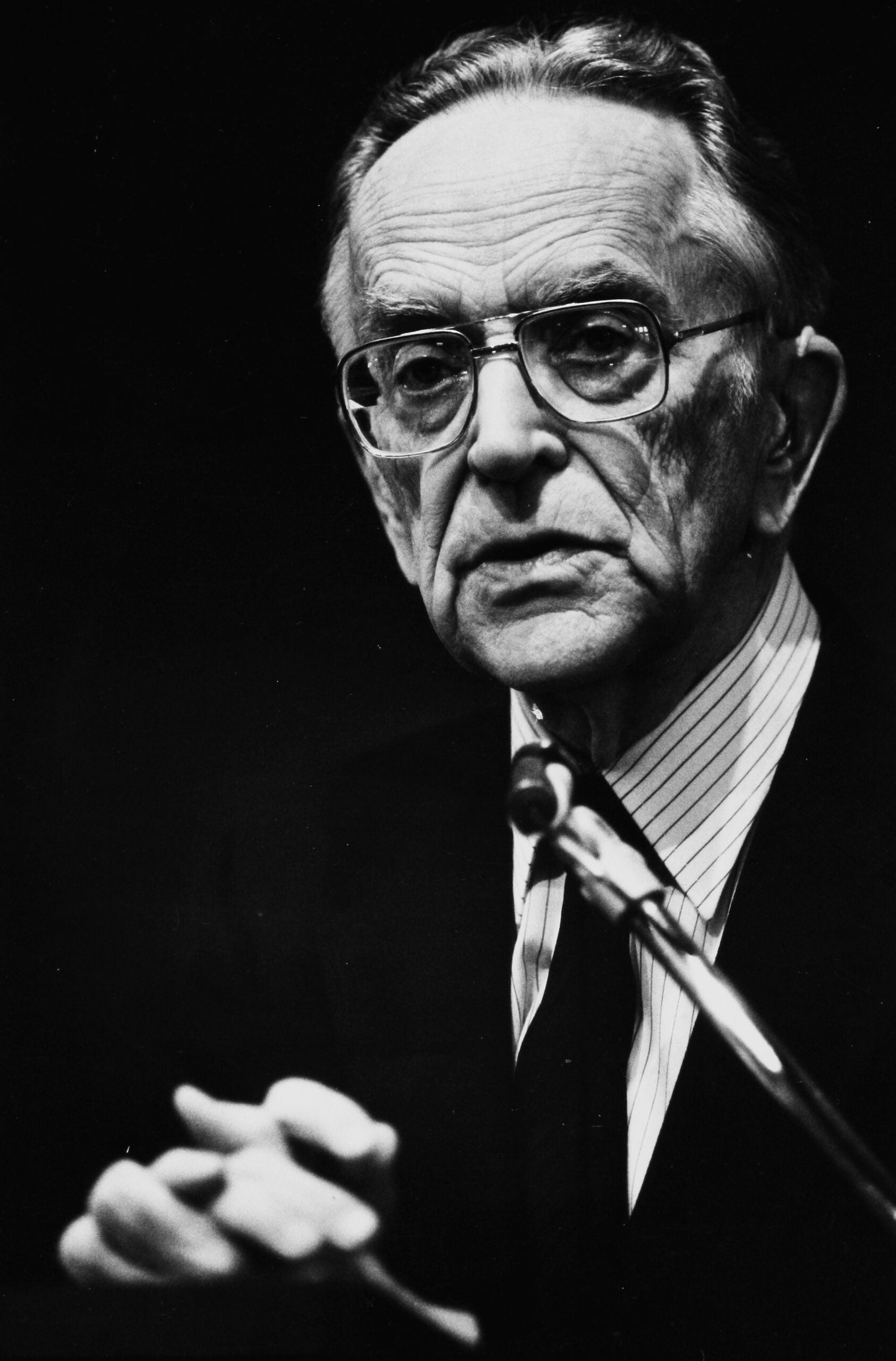

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry A. Blackmun ’32 died March 4 at age 90. Appointed to the Court in 1970 by President Nixon, he retired in 1994 after a 24-year career on the Court marked by a movement from moderate conservatism to outspoken liberalism. A 1932 graduate of HLS, Justice Blackmun returned to the School on many occasions, for the Centennial Celebration, to receive the HLSA Award, to deliver the Class Day speech, and to speak to students at HLS’s Saturday School.

Numerous Harvard Law School graduates had the honor of clerking for the Justice. Among them is Penda Hair ’78 – founding principal and codirector of The Advancement Project, a public policy advocacy organization in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles – who served as a Blackmun clerk for the 1979-80 term. The Bulletin asked Hair to comment on the Justice’s legacy.

Justice Harry A. Blackmun will go down in history as the author of Roe v. Wade, but his contribution is much greater than that one seminal decision. Justice Blackmun’s life on and off the Court reflects a deep passion for protecting the disadvantaged and oppressed. Two hallmarks of his work are compassion for the real people involved in constitutional disputes and his eloquence of expression.

In the area of race discrimination, Justice Blackmun wrote more than 30 opinions addressing constitutional and statutory issues. In his opinion in the landmark 1978 case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, he cogently captured both constitutional theory and the reality of American life and history in the oft-quoted conclusion: “In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race.”

Justice Blackmun’s support for affirmative action flows from a deep understanding of the persistence of racism. Dissenting from the Court’s invalidation of a minority business development program, he referred to “those who have suffered the pains of economic discrimination in the construction trades for so long.” A true Civil War buff, Justice Blackmun prominently displayed on a wall in his chambers the bill of sale for the purchase of a twelve-year-old slave. He made the connection between slavery and the continuing impact of race today in the minority business case, proclaiming: “I never thought I would see the day when the city of Richmond, Virginia, the cradle of the Old Confederacy, sought on its own, within a narrow confine, to lessen the stark impact of persistent discrimination.”

In the true common law tradition, Justice Blackmun was interested in the stories behind the cases that came before the Supreme Court. In a case of an abused child and an unresponsive child protection agency, Justice Blackmun bemoaned “poor Joshua!” Similarly eloquent and empathetic in protesting the Court’s decision to uphold a state’s denial of Medicaid funding for abortions, Justice Blackmun focused on the “individual woman . . . indigent and financially helpless” and noted: “There is another world ‘out there.’”

Justice Blackmun’s personal relationships mirrored his judicial concern for human beings. With a style that was very low key and unassuming, he demonstrated a continuing interest in the lives of all those around him, from the Supreme Court guards to the cafeteria workers to the staff in his own chambers. Every morning the law clerks joined him for breakfast, usually discussing the news of the day, starting with the sports pages. When my three male co-clerks and I made it to the finals of the law clerk basketball tournament, our Justice cheered as loudly as anyone for us in the championship game. I felt that the Justice was particularly delighted that I participated in the weekly basketball games, although he never said that directly. Justice Blackmun hired more women law clerks than any other Justice and supported us during and after the clerkship. His death is a tremendous loss to those of us who were privileged to know him and to the entire country.

–Penda Hair ’78