Breaking out of the mold, solo practitioners forge their own way

It was the kind of day made for a walk in the park, a splash in the fountain, a taste of the good life. On a June weekend morning in New York City about a decade ago, tourists and natives alike were savoring the best the city had to offer. As he made his way to the office, Andy Epstein saw it all, and saw something was not right. Until that point, he said, “I didn’t even think it was strange to go to work on a summer Sunday morning. I think I realized then that I didn’t want to live my life this way.”

That life included days when he worked the putative bankers’ hours of 9:00 to 4:00 (except in his case the 4:00 signified a.m.), days when he would take his fiancée to a rare dinner out only to fall asleep at the table, days when, after moving “mountains of paperwork back and forth, “he thought, “When did I decide I wanted to do this with my life?”

So he changed his life, taking a career path far removed from the large New York City law firm where he worked. Like a small number of his fellow HLS alumni, Epstein ’89 eventually started his own practice, making his own hours and his own work, and discovering the rewards and challenges of being his own boss.

These solo practitioners have chosen the work for a variety of reasons. Some eschew the lifestyle and bureaucracy of a law firm; others embrace a particular practice more suited for a solo route; for others, being solo means being home. Regardless of their motivation, the solo practitioners all agree that they have taken the right path for them, a path they say has led to new opportunities and new realizations about the law.

At Your Service

That path, however, can wind in unexpected ways toward a solo practice. For Irwin Russell ’49, “You don’t consciously decide on what you’re going to do. There are a lot of twists and turns along the way.” After all, most solo practitioners in entertainment law don’t normally prepare for their career by drafting regulations for the National Wage Stabilization Board.

At HLS, Russell became interested in labor law. Immediately after law school, he worked for a labor arbitrator, which preceded his stint in Washington for the federal government. After two and a half years with the National Wage Stabilization Board, Russell joined two classmates to open a firm in New York City.

The firm represented several small businesses, and Russell realized that he enjoyed working with entrepreneurs more than negotiating with labor unions. He established his own practice in New York City, where his clients included Elektra Records, later sold to Warner Brothers. Through contacts in the industry, his client base in the entertainment field grew, so that by the early 1960s, Russell focused primarily on entertainment law.

Credit: Michele A.H. Smith/Liaison Entertainment lawyer Irwin Russell says that when he calls a client, “It’s not because the meter’s running.”

In the early ’70s, Russell realized that his practice was best suited for the epicenter of the entertainment business: Southern California. For a time, he left the law, working as executive vice president for David Wolper’s television and film production company, managing the business and negotiating many contracts. He later partnered in a small firm. But as his name became established in Hollywood, Russell set out on his own, with a style and approach unique to his environment-a lawyer in the entertainment business who never keeps a timesheet, who seals deals with handshakes, and who sees clients as friends, not just business opportunities.

“I really enjoy the interaction with very bright entrepreneurial people. I think I’ve gotten that more with a solo practice. That’s a great personal satisfaction,” Russell said.

“I’m an oddball,” he added. “I’ve never had a signed retainer agreement with any client. I don’t believe in it. I think that goes to the core of being a solo practitioner. It’s the difference of the old-fashioned personal service.”

Russell says that relying on billable hours can poison the lawyer-client relationship. “I see these lawyers, every time the phone rings there’s a drop charge for $75,” he said. “It’s very contrary to what a relationship with a client should be in my view. When I call up a client, it’s not because the meter’s running.”

One client who attracts widespread attention is Michael Eisner, CEO of the Walt Disney Company. Russell has represented him for 25 years, since Eisner was a television executive at ABC. Since 1987, Russell also has served as a member of Disney’s board of directors. For Eisner and others, Russell negotiates executive compensation and crafts other deals, always, he says, focusing on preventing disputes between parties.

“It’s been an entrepreneurial business adviser-type practice rather than a litigation practice,” Russell said. “I am anti-litigation. I’m more of a problem-solver, a doer.”

While Russell is available to his clients every day, he acknowledges that such personal service comes with a price: the practice is never far behind, no matter where he travels. That’s one reason he particularly enjoys escaping to the ski slopes, where he can leave the fax machine and the computer behind for a few hours.

Although representing actors or the “talent” in the industry has rarely been a feature of Russell’s practice, Stuart Rees ’97 is beginning his career doing just that. Last year, Rees became the first attorney to specialize in representing comic strip artists, who previously had to either represent themselves in negotiations with the six major syndicates that control the industry or hire an attorney who didn’t understand the business. The syndicates hold most of the bargaining power, according to Rees, accepting only about 20 new artists a year out of 7,000 to 9,000 submissions. His presence allows artists to use their limited bargaining power most effectively, and provides their only source of objective information, said Rees.

Rees’s business developed when, as a third-year student at HLS, he wrote a paper on syndicated contracts and posted it on the Internet. The document garnered industry attention, and he learned of a community of artists “starved for information.”

As an advocate for the artists, Rees negotiates the money share, the duration of the contract with the syndicate, and copyright. He feels a kinship with the artists—he drew a strip for the Harvard Law Record and has always been a devotee of the comics. Yet he also appreciates the business perspective of the syndicates, which serves him well, he said, in negotiations. “I understand the corporate mindset. I understand the artist mindset. Often when they come to loggerheads, I can make them see the middle ground.”

He recently left his associate position with the Boston law firm Bingham Dana, where he’d been able to work part-time as he established his solo practice. “I’m never going to earn what people earn in a big firm,” said Rees. “Because it’s such a struggling field, I don’t expect anyone else to bother going into it. All I can be sure of is to be able to earn a nice, normal living off reasonable hours.”

My Hometown

Credit: Steven Rubin Hank Fincher waves to friends outside his office in his hometown of Cookeville, Ten..

For at least two HLS classmates, Hank Fincher ’94 and James “Brex” Wyatt ’94, the quest to earn a nice, normal living has brought them home again.

When even the mid-size city of Nashville seemed too large and impersonal for him, Fincher knew it was time to go home, to Cookeville, Tenn., the county seat of Putnam County, population 26,000. Fincher opened his solo practice in the main square near the courthouse—three minutes from his house—after one and a half years in a Nashville law firm. “I’d been there just a little while and decided something just wasn’t clicking for me,” Fincher said. “I like the autonomy of a solo practice and the opportunity to get in a courtroom. In a big firm that takes time, and I didn’t want to wait.”

Wyatt has nothing against the big city. In fact, he opened another branch of his solo practice in Atlanta in March, upon being awarded a government contract to provide real estate closing services for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. But he’s glad he launched his first solo practice in his hometown of Calhoun, Ga., about an hour’s drive north from Atlanta. “I think it’s easier to go to a place where you’re familiar, where you’re known, and where you have family.”

The HLS classmates, both 30 years old, knew, however, that starting a business requires more than hometown roots. It also takes preparation, capital, and nerves.

After graduating from HLS, Wyatt worked in the Pentagon on government contracts for the Department of Defense, Defense Intelligence Agency, with the benefit of the Law School’s Low Income Protection Plan (LIPP). When his salary exceeded the LIPP cap, Wyatt moved on to United States Fidelity & Guaranty in Baltimore. When USF & G was acquired by St. Paul Insurance, employees were given the opportunity to relocate to St. Paul, Minn.

Wyatt instead saw the opportunity he’d been planning for since law school. At HLS, he had worked for large firms in summer jobs and “didn’t get much out of it.” Besides, he said, “I always had a dream of starting my own firm.”

Aided by a severance package from his employer, Wyatt started his practice in December 1998. While in law school, he had read every article and book available on solo practice, and followed the career of others who had taken the same route. Long before he put out a shingle, he had considered budgeting, dealing with banks and clients, and start-up costs for the business, an important prerequisite for attorneys interested in starting their own practice, he said.

“Anyone interested in starting their own practice shouldn’t wait until they’re ready to do it to start researching it. It should be like a hobby,” said Wyatt. “For folks who have children or a lot of responsibility, it may be difficult to make it. It’s for people who have that sense of adventure, who aren’t afraid.”

Of course, said Fincher, many attorneys have reason to fear launching a solo venture. Regardless of his confidence in his legal abilities, Fincher understood that the business aspect of the practice was a new, strange world, one in which lawyers are often ill trained. He was inspired to open his practice by the example of a childhood friend who had launched his own successful law practice, but he also prepared for any contingency.

“There were various disaster scenarios I went to before I decided to jump,” he said, “but [my wife and I] were able to arrange our finances so if I didn’t get too much business, we could get by.”

Fincher started his firm in January 1997. Like Wyatt, he used contacts from his family and childhood to help build the practice. He also gained recognition from a notorious local case that attracted national attention.

Fincher, who hopes to run for the Tennessee Legislature in the future, served as the campaign manager in 1998 for Charlotte Burks, whose husband was running for the state legislature when he was allegedly murdered by his opponent shortly before the election. Though she had to mount a write-in campaign for the state seat, Burks won with 95 percent of the vote against her husband’s alleged killer, who currently awaits trial in the county jail.

Though he gained publicity and respect for his role in that sensational case, Fincher emphasizes the day-to-day service of a small-town lawyer. When he worked for a law firm, the partners told him to concentrate on corporate bankruptcy work, which was not what he wanted to do. Now, he runs a general practice, which includes civil litigation, personal injury, family law, probate work, and labor arbitration. The variety of the work—and the chance to help people in a variety of ways—excites him most about his practice.

“I wanted to work with real people where you could make a difference on a daily basis,” Fincher said. “I never would have thought there’d be so much here. It’s great. It’s invigorating. You don’t get bogged down.”

Wyatt has focused on a narrower field in his practice, concentrating on real estate. Some people ask him why he chose real estate over litigation, and he says all you have to do is spend some time in his office to understand.

“One day, there was a couple outside waiting for their loan closing. They were just so happy and excited, talking about their new bedroom suite and their new drapes,” Wyatt recalled. His assistant noticed the couple and told Wyatt: “I know why you enjoy this so much. You’re dealing with positive people, doing something very momentous.”

For both men, the work is financially rewarding as well. Wyatt hopes to retire in 15 years; Fincher is making far more money on his own than he did at a firm. Even though the hours of work often rival the time demands of a firm, the work itself is energizing, they agree.

“I’m probably working harder now than I ever have in my career, but it’s not hard because there’s no stress. If you’re working for yourself, it’s something you can enjoy and excel at,” said Wyatt.

“You don’t have to go to the big city to have a good practice and a good life,” said Fincher. “I actually think it helps to get out of the firm environment.”

A Firm Decision

It certainly helped Sara Staman and Andy Epstein. Staman ’86 spent most of her career working for mid-size law firms in Philadelphia, where she was raised. She became the senior woman and one of the most productive members of her firm, billing 2,400 hours a year. But her billable hours and her life changed a little over a year ago, when she attended a bar association program on women’s leadership.

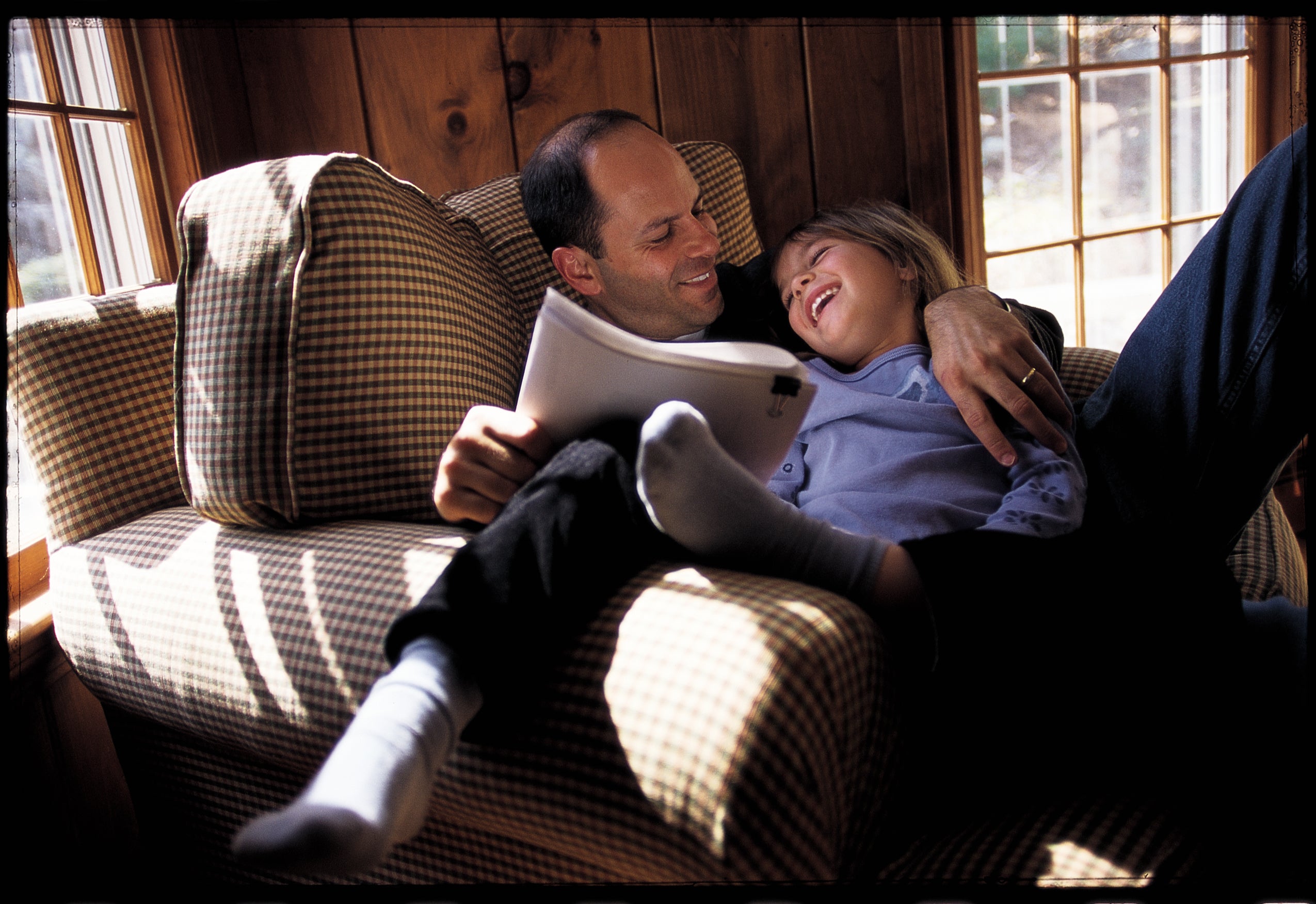

Credit: Steven Rubin Andy Epstein, in his usual business garb, works as a legal consultant to high-tech firms out of his home office in Dover, Mass.

“The bottom line of this presentation was that there is a lot of dissatisfaction in what we do. You have to look at what motivates you personally,” said Staman. “You can be a very successful lawyer and yet not be rewarded by the practice. I took that very much to heart.”

Staman enjoyed her work in civil litigation but felt “general dissatisfaction with law firm life.” Inspired by the bar association program, she moved out of the law firm and into more comfortable surroundings—her home.

Now, Staman accepts contract work from firms and has established a small solo practice. Her assignments from firms range from small projects that take a day, to complex litigation that can take six months. She is attracting more and more business through word-of-mouth but can accept or reject work to fit her lifestyle.

“One of the glories in what I’m doing is that I’m able to enjoy life outside law. You have the advantage of saying no,” she said. “I’m striving to have enough freedom to say that on Tuesdays, I’ll be committed to Meals on Wheels or some other volunteer activity.”

That kind of flexibility also attracted Andy Epstein to a solo practice. But first he had to decide if he wanted to be a lawyer at all. Starting at HLS, Epstein had always expected to work in a large law firm. Indeed, when he worked in mergers and acquisitions in a New York City firm during a summer in law school, it seemed at first the culmination of all he strove for.

“Just being exposed to those big M&A deals and working in Manhattan, the whole experience was mind-boggling,” he said. “It was tremendously exciting. I was working on deals that you read about in the newspaper.”

But once Epstein began to work in Manhattan after graduation, the lifestyle of the city and the demands of firm life soon wore on him. He wanted to get married and raise children but not with a job that made family life nearly nonexistent. He left his job, two years after he asked his future wife to move to New York with him, and the couple moved back to Boston.

He then found a job in a mid-size firm in Boston, which provided better hours and clients he enjoyed working with, but not much more satisfaction. Six months later, he visited Dr. Mark Byers, director of Student Life Counseling at HLS, wondering why he ever went to law school.

The vocational tests he took did not assuage his concern. His test results matched those with the highest dropout rate among lawyers. In fact, his career orientation results matched more closely to flight attendants than to lawyers. He could have changed his vocation; instead he changed his direction.

Sparked by his interest in the software and technology field, he wrote to Lotus Development Corporation, a high-tech company based in Cambridge. There, he found an in-house job that gave him a new perspective on the law, and an area of expertise he would eventually tap for his own practice.

“I thought being a part of a business would be interesting,” said Epstein. “I wasn’t just pumping out documents. Going to Lotus was like a change of career, not just job. I felt I had a lot more responsibility. People within the company would actually seek out lawyers to help them do their job, whereas in other companies, people avoid lawyers because they represent obstacles. You really feel like you’re contributing to the business. I never thought I could have fun being a lawyer, and it was truly fun being a lawyer there.”

He moved from Lotus in 1995 to an Internet division of AT&T, which was later sold to a smaller start-up company. When that company filed for bankruptcy, Epstein became a legal consultant—a foreign concept to many in the legal field but not to those in high technology. Epstein’s experience had shown him that high-tech companies often used consultants and independent contractors. “To lawyers, I say I’m a solo practitioner, but they don’t really understand what I do. To high-tech types, I say I’m a legal consultant, and they understand immediately.”

Furthermore, high-tech companies rarely expect “face time” from their consultants; it’s normal practice to do most or all of the work by phone, fax, and e-mail, he said. Thus, Epstein practices most days out of his home office in Dover, Mass., though his work mirrors that of a traditional in-house counsel. “I actually tend to forget that I’m an outside lawyer,” he said. “I tend to think and act like an in-house lawyer, and I think that’s what my clients want. A client of mine introduced me as her ‘out-house counsel.’ I thought that was funny and apt.”

With his background in technology and contacts from Lotus, business is booming, Epstein said, requiring him to turn down new clients every week. His fees are lower than downtown firms, but his income is higher than that of many of his peers in either law firms or in-house positions. He works long hours still but has the flexibility to take his two young children to school and child care, and to spend time with them until they go to bed.

“I’ve stumbled into something that’s financially rewarding, where the work fits into my life rather than vice versa,” said Epstein.

Finding a Niche

Credit: Rick Rappaport In the Multnomah Courthouse in Portland, Oreg., Susan Reese consults with a client charged with several felonies. He was later acquitted.

Susan Elizabeth Reese ’72 discovered her niche early. At 13, she read about the case of Caryl Chessman, a man convicted of several robberies and sex crimes in California in 1948. Chessman, who wrote books while in prison and professed his innocence, was executed in 1960 under a law that allowed capital punishment in kidnapping cases even when the victim was not killed.

Reese’s outrage at the case inspired her to correspond with Chessman’s attorney, Rosalie Asher, and sparked her interest in the anti-death penalty movement. She discovered then a principle she would oft repeat to indignant observers of her work: All people, regardless of the crime of which they are accused, deserve a zealous advocate.

At the School, Reese learned to develop her focus on defense work in an environment, she said, “not known for producing criminal defense lawyers.” She cofounded the Prison Legal Assistance Project at HLS and “majored in [Alan] Dershowitz,” influenced particularly by the professor’s advanced criminal procedure class.

After graduating, Reese worked in legal aid in Connecticut for a year before traveling west to Portland, Oreg. The public defenders’ office there was not hiring and most law firms didn’t have a criminal defense practice, so she opened her own practice. Reese credits N. Robert Stoll ’68, with whom she shared an office, for introducing her to judges and lawyers and helping her make contacts to attract clients.

When her practice began, she accepted clients with charges ranging from misdemeanors to murder. But she gained the most attention from representing people charged with sexual abuse. As she began taking these cases, Reese would often draw intense media attention, leading other people charged with the crime to seek her counsel.

Now, a primary area of her practice is sexual abuse cases. She takes on these cases, she said, to counter a political climate in which the accusation of sexual abuse can ruin innocent people’s lives. “The accusation itself carries so much of a stigma that it’s difficult to overcome it even if you’re exonerated,” said Reese. “A lot of people are falsely accused. It’s highly politicized and there’s rarely a middle ground. There’s not much plea bargaining in these cases.”

While her clients often face the disdain of the public, she too has faced hostility for representing them. Feminists have questioned how she could represent clients who are often men accused of assaulting women. Yet she says that awareness is increasing about the menace of false accusations, as is understanding about her efforts.

“I get a lot of folks who say, ‘How can you possibly defend them?’ until they realize that they can be next,” Reese said. “A criminal defense lawyer is a savior for people who are accused.”

The clients who hire her do so because they are willing to trust her with their freedom and reputation and normally do not want another lawyer involved in the case, according to Reese. In addition, Reese acknowledges the difficulty of any attorney who is accustomed to working solo taking on partners. Indeed, three previous attempts to form partnerships with other attorneys have dissolved.

“It’s hard when you start out solo because you have your own style and your own approach,” she said. “It’s difficult to merge with another person unless you have extremely similar interests.”

The demands of her solo practice often require work on nights and weekends, and time away from her husband, John Painter, Jr., a Nieman Fellow in 1977 and currently a criminal justice reporter for the Oregonian newspaper. The compensation is also less than that of many of her colleagues. Yet she knows that she has made the right choice, one shaped by a 13-year-old girl searching for justice.

“I’m undoubtedly making less money than people in the big law firms, but at the same time I have the luxury of picking the clients that I want, so it’s worth it to me,” said Reese.

For Jonathan Massey ’88, the luxury of working with HLS Professor Laurence Tribe ’66 pulled him away from a job in a firm to his solo specialty. After clerking for Supreme Court Justice William Brennan, Jr. ’31 (and handing in Brennan’s resignation to President Bush), Massey interviewed with several firms, with an eye toward working in the Solicitor General’s Office in the future. But then Tribe, whom Massey assisted as a researcher when he was a student, called for help on a project.

“He’s such a wonderful person to work with that I would try to work with him at any conceivable opportunity,” Massey said. “I probably would have gone to a firm had [Tribe] not had the need for help with a brief or two. Once I did that, I realized I could pay the bills without working at a firm.”

Since the early 1990s, Massey has collaborated with Tribe as part of a group of former students who assist the constitutional law professor. Several cases involving large punitive damages have reached the Supreme Court. For example, Massey’s brief helped preserve a $10 million award against a West Virginia oil and gas producer, a case argued by Tribe before the Supreme Court. Often backing plaintiffs in appellate cases, Massey also has worked with several states to craft settlements with tobacco companies.

Appellate work in particular suits the life of a solo practitioner, he says. It does not require the large resources and document production often needed at trial, and allows attorneys to work in any location. “Solos often can handle an appeal by themselves. A lot of plaintiffs’ lawyers don’t like to do appeals. They’d rather try another case,” he said.

His collaboration with Tribe has helped Massey generate his own client base. Working out of his home office in Washington, D.C., Massey spends most of his days and some of his nights writing briefs for clients all over the country. His wife, Mandy Katz, works as a writer from her own home office on a different floor of the house. The couple manage to incorporate more family time with their three children during the day but find that work constantly beckons them.

“I wind up working all the time,” he said. “You can never get away. That’s one downside of the home office. You never leave. The hardest thing about being a solo practitioner is managing. My fault is I take on too much work and find myself too busy. The business part is obviously the worst part about being solo.”

Yet Massey also touts the flexibility and freedom of the solo practice, and the independence of handling one’s own cases. For many lawyers, he says, working in a firm is the safer route, but he urges prospective lawyers to consider the opportunities available in different areas of practice.

Credit: Steven Rubin Daniel Taylor shows his admiration for his secretary and paralegal, Rebecca Taylor, who is also his wife.

Daniel L. Taylor ’68 found his latest niche in a career that has spanned different practice areas. He eschewed a job in a law firm after graduation, noting the relatively short pay and long hours required. Instead, he opened his own practice in Winston-Salem, in his home state of North Carolina. At that time, he said, professionals were just beginning to incorporate as businesses, and many clients — often doctors, dentists, and some lawyers — would turn to Taylor for counsel on corporate tax and estate planning.

As a new attorney and in his own practice, Taylor said that he learned a lesson that would serve him again and again throughout his career. He read everything available on his specialty and stocked a library with the latest literature, a library that Taylor would reconfigure each time he switched specialties.

After ten years in corporate law, Taylor found that competing with law firms in his specialty was increasingly difficult. In addition, he yearned to test himself in the courtroom: “Almost all lawyers become civil trial lawyers or wish they would become civil trial lawyers, so I decided I was going to do litigation.”

He spent the next 15 years of his career as a litigator with his own practice before joining a law firm in Dallas. The firm dissolved after only a year, and he returned to North Carolina, once again a solo practitioner. His experience wasn’t bad; yet he also observed that lawyers often have difficulty coexisting in the firm environment.

“The thing about law firms people need to recognize is lawyers don’t seem to work well together,” Taylor said. “You can look at the firms in any city today, and in five years, half of them will be gone.”

About 18 months ago, Taylor changed his practice again. He discovered elder law, an emerging field that encompasses estate, financial, and Medicaid planning; long-term care; pensions; wills; living trusts; and powers of attorney. Now practicing in Charlotte, Taylor said that most firms in the city offer traditional estate planning but not the broad range of services that he does. Changing his specialty was made easier, said Taylor, by his status as solo practitioner.

“It’s an interesting thing because if you’re in a firm it’s most likely you’d never make these switches,” he said. “When you switch like I did, you have to become an expert in these fields. It allows your horizons to expand.”

For solo practitioners, Taylor emphasizes the importance of marketing to compete with firms with much greater resources. His library contains several books on business in addition to the books on the law. Many lawyers, he says, speak in the lingo of the profession. But to communicate with the public, attorneys should address their specific concerns, like protecting assets for families.

“Marketing is something most lawyers don’t know anything about,” said Taylor. “When I came out of law school, marketing was a no-no. All you could do was hang out a shingle, and the sign couldn’t be more than five inches high. If you do that, you’ll be like the Maytag repairman. Your phone won’t ring.”

His phone is ringing so often that he is considering hiring an associate for the practice. He knows, however, that the life of a solo practitioner can sway with the economic times, with the larger competitors encroaching on his territory, with the sheer luck that can buoy or destroy any small business. It’s not all about the money, he says. And, as with most people who choose to fly solo and find their own place in the world, he means it.

“Realistically, my classmates in large firms are earning more money, but I’m happy and supporting my family and I’m making an income that I feel is all right,” said Taylor. “I’ve been able to do a lot of creative thinking and try new ideas, and I certainly know I have a broader spectrum of practice than I ever would have had if I worked for a firm. That’s very satisfying to me.”