Major League Baseball executive Sandy Alderson works to maintain the allure of the national pastime

Fenway Park pulsed with the sounds of 33,000 fans lucky enough to score tickets in the middle of a pennant race. They pleaded and yelled and stomped and groaned at every pop-up, called strike, or double play. They shook the old place when Manny Ramirez hammered a ball over the Green Monster. Boy, this is fun.

But not for Sandy Alderson ’76. For Alderson, this is a job. It’s a job he likes, most of the time. On this July night, however, he may have preferred a career in, say, drilling holes in scorching asphalt to being executive vice president of baseball operations for Major League Baseball (MLB). Especially when his cell phone rang with a call from a New York Times reporter asking him, yet again, about a subject that for a few weeks in the summer was the sports world’s equivalent of the Cuban missile crisis. The reporter had acquired a copy of a memo Alderson had written, which noted that, when certain umpires worked behind the plate, more pitches were thrown than in an average game. That, he said, indicated that they should call more strikes, should, indeed, “hunt for strikes.” This turn of phrase burned Alderson, who was roundly blasted for perhaps the first time in his 20 years associated with the game of baseball. The umpires filed a grievance over the memo, which, they claimed, would force them to call strikes willy-nilly to keep pitch counts down and thus keep their jobs. The very integrity of the game had been compromised, some said.

Nonsense, said Alderson. He believes a simple statistical analysis had been misinterpreted and overblown.

“It’s all a question of performance against standards, and the most fundamental standard is the strike zone,” he said. “You can’t have 85 [umpires] with their own standard.”

He doesn’t regret the memo or any of his ongoing efforts to enforce the rules of the game and preserve and enhance its popularity. “If you’re going to get something accomplished,” said Alderson, “it’s not going to happen of its own weight. You’ve got to keep pushing.”

Since he began three years ago in his current position, Alderson has pushed his view that escalating salaries, disparate payrolls, and competitive imbalance are hurting the sport. No one yet knows if that view will prevail in negotiations for a new collective bargaining agreement, which will take place after the season. But when push comes to shove, Alderson tends to be the person still standing. That was true when he took on the umpires union two years ago, greeting a mass resignation with the retort: “This is either a threat to be ignored or an offer to be accepted.” It was true when, as a baseball outsider, he molded the personnel of a team that would become a World Series champion. And it was true when he served in the Marine Corps and fought in Vietnam.

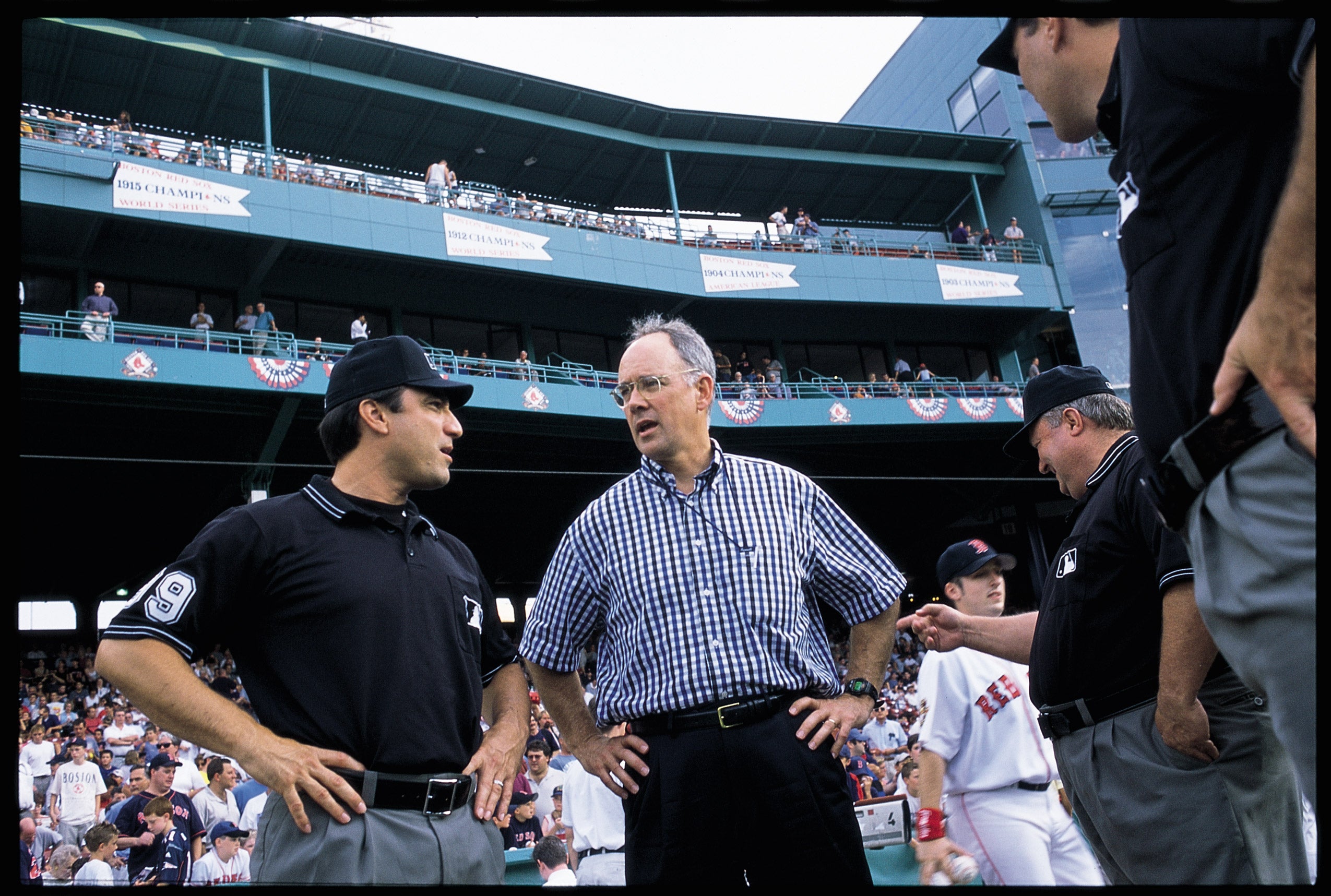

His job brings him to Fenway and many other ballparks around the country and even around the world every baseball season. In addition to his supervision of umpires, whom he met with privately for nearly an hour before the Red Sox game, Alderson oversees international initiatives, such as Major League Baseball’s participation in the 2000 Olympics in Australia and the groundbreaking exhibition games between the Baltimore Orioles and the Cuban national team in 1999.

But much of his job involves simply watching–the length of games (he’d like them to be shorter), the interplay of pitchers and batters (pitchers should not intentionally throw at batters, and yes, he says, you know it when you see it), and always the umpires. As the Boston Red Sox play the Toronto Blue Jays, he watches things no one else in the stands watches, thinks things no one else thinks. On one hit to deep center field, the ball bounces on the grass and off a wall. He praises the effort–of the umpire, who sprints from second base to the outfield to call it a ground rule double. That, he says, is the kind of hustle he likes to see.

Soon, however, he sees something he doesn’t like. “Where was that?” he groans, as the home plate umpire calls a ball on Ramirez. He doesn’t have anything against Ramirez or the Red Sox, though he doesn’t think much of the $20 million a year they’re paying him. He just believes the umpire should have called a strike. And as the fans rise in unison shortly thereafter, when Ramirez hits a mammoth shot onto Lansdowne Street, no Red Sox fan doubts that the team was wise to sign the slugger to a $160 million contract. But Alderson has done the math, a cost-benefit analysis not on Ramirez specifically but on several other high-profile free agent signings. “Does it bear out financially? In most cases, no,” he said. “Does it bear out competitively? No.”

Soon, however, he sees something he doesn’t like. “Where was that?” he groans, as the home plate umpire calls a ball on Ramirez. He doesn’t have anything against Ramirez or the Red Sox, though he doesn’t think much of the $20 million a year they’re paying him. He just believes the umpire should have called a strike. And as the fans rise in unison shortly thereafter, when Ramirez hits a mammoth shot onto Lansdowne Street, no Red Sox fan doubts that the team was wise to sign the slugger to a $160 million contract. But Alderson has done the math, a cost-benefit analysis not on Ramirez specifically but on several other high-profile free agent signings. “Does it bear out financially? In most cases, no,” he said. “Does it bear out competitively? No.”

Later, when he takes the call from the Times reporter, people turn in their seats to see a casually dressed 53-year-old man speaking with clenched jaw into a cell phone about the strike zone and umpires and pitch counts. He leaves early to catch the shuttle to New York, MLB headquarters. All in a day’s work.

The son of a career Air Force pilot, Alderson developed an important skill early on in the peripatetic life of a military family. He learned how to adapt to different environments, different circumstances.

On a ROTC scholarship, he attended Dartmouth. Though the United States was then embroiled in Vietnam, the decision to join the military was not difficult, given his background, Alderson said. He made two brief trips to Vietnam, to see his father and to work as a foreign correspondent. On his third trip in 1971, he went as a soldier, a Marine infantry officer, for an eight-month tour of duty.

“It really became more of a matter of waiting things out than having any thought of doing something really beneficial,” said Alderson. “On the other hand, there were, at that time, modest things that we could do to ameliorate the immediate situation of the Vietnamese with whom we were involved and also the U.S. servicemen who were partly my responsibility. . . . I think we felt a responsibility to the country. I certainly feel we had a responsibility to act, had anobligation to act responsibly in that situation, and so what we did was toward that end.”

He might have stayed in the military but for his acceptance to HLS. Being a veteran among many students who had protested the war did not heighten the challenge in any way, Alderson said. The School was rigorous, for him and for everyone, and he fit in just fine, he said.

After graduating, he worked for Farella Braun + Martel in San Francisco. Roy Eisenhardt, one of the firm’s partners, left to become president of the Oakland A’s when his father-in-law bought the team. Alderson did legal work on the sale and joined the team as general counsel in 1981. He did more than general counsel work, however. He attended minor league games with scouts, traveled with the team, interacted with baseball lifers, like Billy Martin, then manager of the team. In 1983 Martin was fired, and many of his colleagues in the front office left with him. To fill the general manager position, the most crucial position in the organization, Eisenhardt chose Alderson, a man in his mid-30s who had last put on a baseball uniform while playing at Dartmouth.

This was not the way things worked in baseball. You had to ride the buses in the minors, pay your dues on the field and in the locker room from the time you were 18 years old. And for all the jobs in the world for which an HLS degree is a golden pass, this most assuredly was not one of them. In fact, for the “real” baseball men, the Ivy League pedigree only made things worse.

“It was off-putting to a lot of people,” Alderson said. “We’re often judged on the basis of our background and our stereotype based on history and associations, but I recognized that that would be a problem.”

So he did something about it. He kept his mouth shut, he listened, and he learned the lexicon of the game, both on and off the field. He also understood that he didn’t need to evaluate talent as much as establish a philosophy and ask the baseball people to find the players who would fit it. His approach, borrowed from baseball writer Bill James, relied on batters with power and a high on-base percentage and pitchers who didn’t give up many walks or home runs. Alderson drafted future stars Mark McGwire, JosÈ Canseco, and Jason Giambi and built a team that played in three straight World Series, winning one of them in 1989. Even the baseball men had to approve. For a time, he and his team were on top, and loving every minute of it.

“It was fun to be around. It was a team with more than self-confidence–you know, a swagger,” said Alderson. “I can still remember coming out of Fenway Park in 1988 after beating the Red Sox in the playoffs and walking underneath the stands from the visiting clubhouse to the buses, and it was a great feeling.”

“On the other hand, nothing lasts forever,” he added. “I think what inevitably happens these days is that money and other things get in the way.”

And that is the crux of the problem.

Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig, who three years ago created a new position in his office especially for Alderson, never comments on player contracts. But Alderson sure does. When Kevin Brown signed with the L.A. Dodgers for more than $100 million, he called it “an affront to baseball.” He castigated Mike Hampton for pointing to the quality of the Colorado schools as an impetus to sign with the Rockies rather than the $121 million on the table. And he was “stupefied” when the Texas Rangers signed Alex Rodriguez for more than a quarter of a billion dollars over ten years. “Clearly we have a crisis situation in the game,” he said on the day the deal was announced, “and it’s time for us to deal with it.”

He speaks with the passion of the truly reformed. Alderson came to his current job, he said, “with a certain amount of baggage.” He represented a small market team forced to trade players–Mark McGwire most prominently–whose salary demands the ball club could not afford. Before that, he had committed some of the same transgressions that he so vigorously decries today. For example, Alderson signed Bob Welch to a substantial, multiyear contract after he won 27 games for the A’s and the Cy Young Award in 1990. Welch won a total of 35 games in the next four seasons.

“You’ve got to learn from your mistakes,” Alderson said. “We continue to rationalize these decisions in ways that are disingenuous. . . . I do not believe that teams with large payrolls have an entitlement to year-after-year success. I don’t think that’s the way the game ought to be perceived.”

Teams with smaller payrolls have little chance to win, Alderson notes; at the time of the game at Fenway in late July, all six division leaders were in the top ten in payroll, continuing a pattern borne out over the past decade. Fans in several cities across North America know–before the season starts–their teams will not make the playoffs.

The commissioner’s office wants to change that. The office established a “blue ribbon panel” on the economics of baseball whose report released last year may serve as a first volley in upcoming negotiations. It recommends increased sharing of revenue from local broadcast rights, a 50 percent “competitive balance tax” on teams that spend above a designated payroll level, and a revised draft system that would allow the worst teams to pluck players from the best. The negotiations promise to pit not only owners against players but high-payroll owners against low-payroll owners. If an agreement is not reached before the 2002 season, MLB may face its ninth strike or lockout since 1972.

But Alderson will not talk about the collective bargaining agreement. Neither he nor anyone in Major League Baseball headquarters will. Baseball fans, of course, would rather talk about the game on the field, anyway. So would Alderson, who cheers with everyone else when Mike Lansing stabs a sharp grounder at short and rifles a throw to first for the out. He jokes to the Red Sox fan sitting beside him: “You don’t need Nomar” Garciaparra, the team’s star shortstop, out for the year till that point with a wrist injury. He doesn’t mention that Lansing, a mediocre big-league player, is making $6 million this year.

Because, after all, this is fun, even for Sandy Alderson.