Expanded program helps Harvard lawyers advance human rights abroad

Commencement is still weeks away, but Chi Mgbako ’05 already feels like a seasoned human rights advocate. She’s been to Rwanda three times in three years, documenting human rights abuses and preparing reports for NGOs like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. In February, Front Line, an NGO for the protection of human rights defenders, published a report she co-wrote on the persecution of human rights activists in Rwanda. For Mgbako, this is testimony to the training she received through Harvard Law School’s Human Rights Program.

“I feel like I’ve come full circle,” said Mgbako. “As a 1L, I went to the Human Rights Program and said I wanted to work in Africa, and I did. Going back for the third time, I really felt I had some expertise. I knew what I was doing, and yet, I was still learning. It was amazing.”

More and more students like Mgbako are finding a niche in human rights advocacy and a home in the HRP, an academic program that has pioneered legal training in international human rights through an interdisciplinary curriculum that combines scholarship with work in the field.

The program has grown from the first handful of interested students in the mid-1980s to some 200 students involved today, coming into its own as an important part of legal education at Harvard, according to James Cavallaro, its associate director.

“Twenty years ago, human rights was a fringe field,” Cavallaro said. “That’s clearly changed. In an increasingly globalized world, human rights has greater importance. It’s a way to help students understand injustice and give them a language to respond to that injustice.”

Established by Professor Henry Steiner ’55 in 1984, the program was among the very first human rights centers instituted at a law school, and the first to offer a human rights curriculum at Harvard University. From humble beginnings, it is now at the center of a vital and energized community of students, practitioners, scholars, alumni and human rights organizations worldwide.

Indeed, while Mgbako may be amazed by the level of support and training she has received, Steiner says students today expect no less.

“At the start, students were puzzled by what this all amounted to, and so was I. We were all learning,” said Steiner, who will step down as director when he retires this July. “Students now assume the program has been here forever. It’s not that it’s no longer maverick, but that it’s so clearly institutionally established. It’s part of the landscape now, and it’s always going to be. It’s wonderful–my fondest dream.”

Students have been the driving force behind the program’s growth from the beginning. In 1988, they established the Harvard Human Rights Journal, now the leading scholarly journal in the field, and more recently they formed the Harvard Law Student Advocates for Human Rights to give students more opportunities to gain practical experience in human rights work. Today, organization members are doing clinical work in Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America and the United States.

“[HLS Advocates] was started because much of the clinical work was limited to the summer or winter breaks or through classes, which meant the work was usually done independently,” said Ronja Bandyopadhyay ’04, who co-founded the organization in 2002 with classmates Daniel Schlanger and Michael Camilleri.

“This was a chance to make sure that everyone who was interested in clinical work could participate–especially 1Ls, who can’t get clinical credit, but they can still get the experience through HLS Advocates,” she said.

Through the organization, Bandyopadhyay, whose parents are from India, found herself steeped in human rights issues in Asia. After working on an amicus brief to the Indian National Human Rights Commission about the forced disappearances of thousands of Sikhs in Punjab, she turned her focus on the Ahmadiyya community, a minority group in Bangladesh.

“The government of Bangladesh declared a ban last year on publications by the Ahmadiyya,” said Bandyopadhyay. In mainstream Islam, there is a “finality of prophethood” that essentially ends with Muhammad, she explained. “But the Ahmadiyya are a Muslim branch that believes a reformer came after Muhammad. Many mainstream Muslims view this as heretical and reject them.”

According to Bandyopadhyay, that rejection has led to harassment and violence against Ahmadis by the majority Muslim population in Bangladesh, and many Muslims there have called for their excommunication. The government’s ban on the group’s publications has raised a red flag in the human rights community, she says.

Last March, Bandyopadhyay and another student from HLS Advocates traveled with their HRP supervisor to Bangladesh to interview government officials and Ahmadis in cities and rural villages to document the situation. This work has been incorporated into a report published recently by Human Rights Watch.

Meeting face-to-face with the people she hoped to help was a powerful experience.

“When you’re talking to real people, [the work] becomes much harder, but that’s also what drives you,” she said. “So many people count on you. When you come from America and an institution like Harvard, you have incredible resources, and people you meet often believe you can solve the problem. You’ve created a hope.

“When you’re talking to real people, [the work] becomes much harder, but that’s also what drives you,” she said. “So many people count on you. When you come from America and an institution like Harvard, you have incredible resources, and people you meet often believe you can solve the problem. You’ve created a hope.

“That makes you want to act, but also truly makes you question what you’re doing and why you’re doing it, and to think critically about human rights work, because your actions will have consequences.”

Since HLS Advocates was founded, the number of students engaged in clinical work (noncredit and credit) has grown from 25 to more than 100, stretching supervisory capacity to the limit. Last year the organization lobbied the law school administration and successfully secured funding for two advocacy fellows to supervise students, more travel abroad and a project to strengthen the links between clinical work and the classroom.

That initiative, known as the Clinical Advocacy Project, pairs on-the-ground clinical experience with a mandatory seminar or classroom workshop in human rights advocacy, so students can evaluate their clinical work and relate it concretely to theory and scholarship. “Human rights advocacy is broader than what is ordinarily bundled in the standard legal curriculum,” Cavallaro said. While independent January and summer-term travel has always been supported through the program, “what’s fundamentally different now is that, through CAP, we’re doing supervised travel,” he added. “Each trip is part of an ongoing research, documentation and advocacy project.”

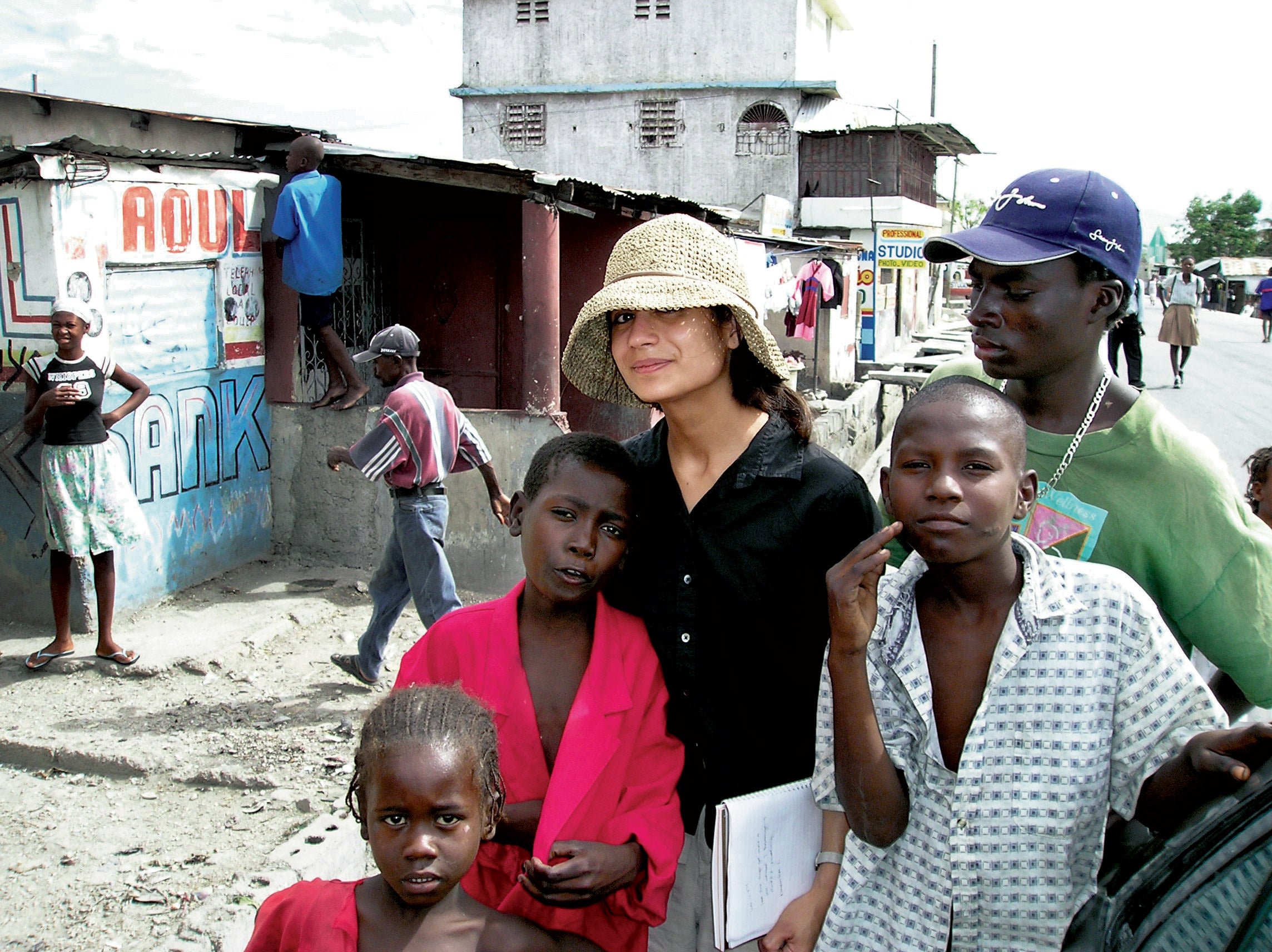

Pooja Bhatia ’06 was curious about fieldwork when she signed on to travel to Haiti with Cavallaro and Benjamin Litman ’06 in January to investigate factional violence and human rights abuses that have erupted since Jean-Bertrand Aristide was ousted from power last year.

“I wanted to see what it was like to practice,” said Bhatia, whose interest was initially sparked by the International Human Rights class she took with Assistant Professor Ryan Goodman last spring. “Haiti is a really interesting country. If it’s not a failed state, it is close to being one. It intrigued me.”

Bhatia did research for the trip during the fall as part of the Human Rights Advocacy seminar taught by Cavallaro and Binaifer Nowrojee LL.M. ’93. She then spent a week in Haiti conducting interviews with government officials and victims of the violence. She gathered information that will be used by an NGO, and took away something else that she couldn’t have learned in the classroom alone.

“I knew there were a lot of conflicting versions of the Haiti story,” she said. “I didn’t realize just how politicized information was, and how difficult it would be to deal with conflicting versions of purportedly the same events. I realized that finding a balance between them would be a challenge.”

Like Bhatia, several other students have gone abroad on CAP missions this year. Human Rights Program advocacy fellow Tyler Giannini took two students to the Thailand-Burma border to interview victims of forced labor. Jamie O’Connell, another advocacy fellow, traveled with three students to a remote area of Guyana to document the impact of mining operations on natural resources and on the health of indigenous people.

The HRP now boasts several hundred alumni actively engaged in human rights work around the world, whether through full-time jobs or part-time and pro bono projects. Nearly a dozen alumni have gone on to establish human rights-focused academic programs at universities worldwide. They are activists, advocates, attorneys, judges, teachers, scholars, entrepreneurs and lawmakers, whom Steiner described as having a “fundamental commitment to human dignity.”

HRP alumni “are out there doing extremely valuable things,” Steiner said. “It’s one of the great prides of the program. They are a tremendous resource.”

Soon one more alumna will be added to that list, in Africa.

“The Human Rights Program has given me a career,” said Mgbako, who has served as president of HLS Advocates this year. “It’s my dream to be a human rights defender. I couldn’t have done it without the support of this community and without being given the chance.”