In a wide-ranging interview, Palfrey and Zittrain survey the future of the Internet

Professor Jonathan Zittrain ’95 is on the phone with his mother.

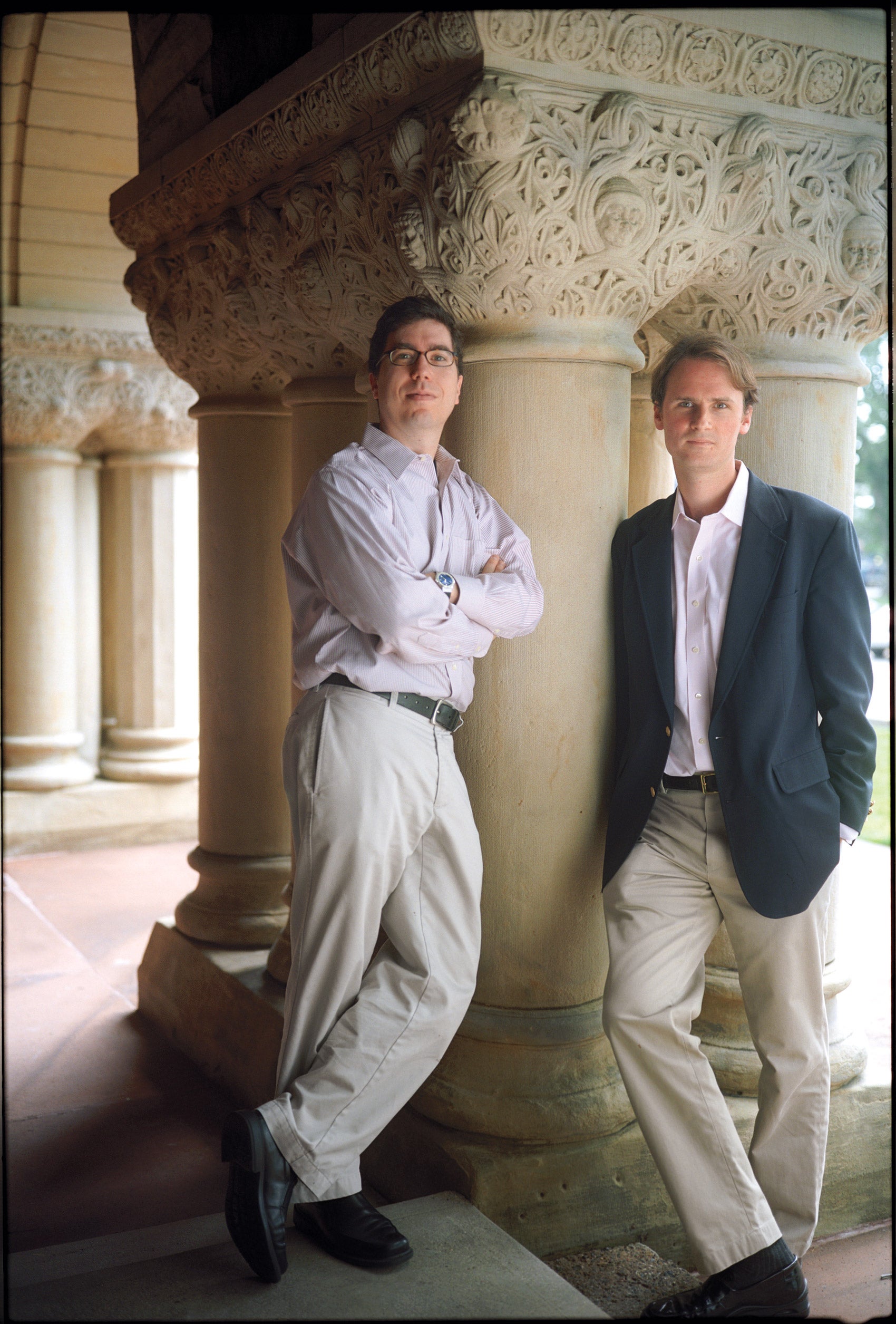

“Are you online these days? Why not?” he asks, with genuine surprise. How can the parent of one of the world’s leading Internet experts live an unconnected life? His mom pleads her case: too many emails. Zittrain suggests how she can reduce spam and other nuisances without giving up the many benefits of the Internet – the very topic, it turns out, that Zittrain and John Palfrey ’01, faculty co-directors of the HLS Berkman Center for Internet & Society, are discussing in Zittrain’s office.

If Zittrain’s mother, let alone corporations and governments, become too frustrated or threatened by certain problems on the Internet, the solutions to those problems may destroy the very qualities that make the Internet a revolutionary medium. As concerns mount about everything from spam to piracy, from privacy to child safety, the web is at a critical juncture in its existence, they argue, its future uncertain and perhaps in serious jeopardy. The wrong choices – toward over-regulation or “closed” technologies—will stifle freedom and innovation, alienate young people, and drive some users to options that are actually less safe.

Both faculty members have published new and highly regarded books that urge thoughtful responses to the Internet’s challenges while preserving the best aspects of the digital world. Zittrain’s work, The Future of the Internet — And How to Stop It, praises the “generativity” of the Internet and PCs – their ability to absorb new programs and technologies so the cyberworld is in a constant state of reinvention — but worries about the movement toward controlled technologies and devices, including the iPhone, which exclude unapproved programs. Palfrey’s book, co-authored with Urs Gasser, faculty director of the Research Center for Information Law at the University of St. Gallen, in Switzerland, is Born Digital – Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives, and examines the digital divide between children who accept the Internet as basic to relationships, learning, work, and more, and their parents who don’t understand the cyberworld and often react in fear.

While Zittrain and Palfrey worry about losing the very best about the Internet, both books ultimately are optimistic, laying out today’s challenges but also presenting reasoned solutions and urging parents, lawmakers, technology companies and others to assume a role in preserving the medium. And, they note, the optimal solutions are likely to come from those who are allowed to continue to use the Internet with as little interference as possible: the digital natives. They expanded on their views in a recent Q&A:

From the standpoint of each of your books, what are the problems that have brought the Internet to this critical juncture?

Palfrey: Some of the problems we see, at least from the perspective of parents and teachers, are that kids are bad, kids are endangered, and kids are dumber than they were before [the Internet]. In each of those cases, there’s some evidence that gives reason for that worry, but I think that fundamentally each one is wrong.

In terms of kids being bad, people worry that kids are meaner on the Net. They worry about aggressive behavior and bullying. I don’t think that’s a fundamental trait in kids— it’s how people have been using this particular set of technologies to mediate their relationships. And it’s something parenting and common sense can address.

In terms of danger, parents are worried their kids will get abducted. That does sometimes happen. But the good news, if there is good news, is, that doesn’t happen any more frequently online, and it doesn’t happen more today than 10 years ago. Again, that’s something where common sense and a little help from technology can go a long way.

Third, in terms of kids being dumber, that’s again just fundamentally untrue. I do think they’re learning in a really different way, and one of our biggest challenges as teachers is, How do we harness most creative things that the most sophisticated kids are doing with this technology and how do we curb their worst excesses?

Zittrain: The problems I see are that the openness of the Internet and of PCs – the “generativity” of these platforms – is too easily subverted. There are twin worries: One, that the essentially anarchist, we-don’t-need-governance-we-can-build-this-barn-ourselves view of technology is starting to hit its limits. Worry two is that the most obvious reaction to that will be as bad as the problem or worse, that we’re going to flee from the suddenly dangerous rainforest into suburbia, and suburbia is a new range of closed or managed networks or closed or managed software. Apple’s iPhone is a great example. Today’s iPhone is open to software but Steve Jobs gets to approve every single piece of software and can reject any software prospectively or retroactively that appears on the iPhone. If this becomes the prevailing model, we’ll lose our shared technology platform where anything can happen from left field – where beneficial disruptions can arise and prove themselves before people have a chance to panic.

Palfrey: This is one of the connecting points of our books. JZ has long celebrated tinkering, that the Internet lets people learn through doing, that as you study it you build it. One of the tenets of the Berkman Center, and this is a core tenet of our book, is that kids can learn by doing something in ways that are transformative for them and for society. That’s the most hopeful aspect of the book. If kids are able to do the more creative stuff, they’ll learn a lot more and also feel empowered, and that will have benefits broadly. But if Jonathan’s story comes out the wrong way, all that goes out the window in terms of what young people can do.

Zittrain: It’s a great point of connection because some perceptions of kids today are that they’re slack-jawed, disengaged, with iPods in their ears, indifferent to what’s going on. Others say no, they’re out there doing cool stuff, making viral videos, honing their Facebook pages and MySpace accounts, and the nerds among them might be writing code. The second group can’t thrive in a world where at the level of code and content, the training wheels never come off, where there’s always a gatekeeping supervisory figure telling them what they can and can’t do. It’s one of an interesting set of futures so different from each other, and we don’t know which one will come about: the one where the training wheels are bolted on for life, and large-scale coding and expression are left to professionals, and one where they aren’t.

Palfrey: Part of JZ’s argument is that you don’t want Steve Jobs as the parental figure for information technologies. But when do you want actual parents involved? This is one of the other problem areas we point to, the abdication of responsibility by parents in what they see as this scary new world. So instead of seeing [the Internet] as a crucial learning zone, where kids are living a lot of their social lives, parents are saying, ‘We don’t understand it and therefore we’re not going to help.’ I think the training wheels analogy is a helpful one because absolutely young kids need training wheels in the environment because there’s a lot of scary stuff they can easily access but you also need a point at which the training wheels come off, so parents are thinking through a learning strategy very similar to, how do you teach them to ride a bike, how do you teach them to be responsible citizens. And it’s something parents have never been asked to do.

John, your book is one of the first to say parents can’t just come to their kids and say, ‘I don’t understand this and so I’m going to make you turn off the computer.’

Palfrey: Nor should you say, ‘I don’t understand this world, so good luck!’ They’re equally bad. The most interesting stories we heard in doing the research was about parents and teachers who truly let young people be their guides, for MySpace or Facebook or YouTube or something more dramatic like Second Life. It’s not like parents are going to spend a lot of time there but they can see that common sense really helps, that as foreign as it seems before they get in there, there are some pretty obvious ways parents can help. But you have to take the first step of getting in there.

Both of you are concerned about the future of the Internet getting hijacked in the wrong direction, through misguided regulation or closed environments or other means. What are the worst things that will happen if the responses to concerns aren’t rational?

[pull-content content=”

Preserving Free Speech on the Internet

In cyberlaw clinic, students help litigate matters of first impression

For students looking for cutting-edge legal work in the realm of new technologies, there may be no better place than the Cyberlaw Clinic at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society.

Zittrain: I have two worries. First, it’s hard to tell people what innovations they will miss out on in a suburbanized environment, not only because it’s hard to visualize innovations that haven’t happened – who would have thought Wikipedia was a good and plausible idea before it happened? – but also because at first many truly disruptive innovations seem stupid or illegal or dicey. It’s not clear to me that Tim Berners-Lee would have had success with the World Wide Web if he’d had to persuade someone at AOL Time Warner that it was good idea at a time when there were no web pages. So, concern one is that there are a bunch of innovations that won’t happen – yet that we won’t know to miss – because of the presence of gatekeepers. My second concern is what happens when you have intermediaries who can, thanks to ubiquitous networks, reprogram the way their customers’ devices work. We’re starting to see examples, such as car navigation systems that get reprogrammed to surreptitiously turn on the microphone so law enforcement can listen in on conversations. It’s weird to see us so casually, through home purchasing choices, building this infrastructure, and to see how none of us appreciates how powerful it is. And once it happens, I think it might be difficult to abandon it. Certainly once governments rely on it, they won’t want to see it go.

Palfrey: My concerns are very similar to Jonathan’s, in the sense that many of them are simply the things we can’t imagine today that young people would do or be able to do that just won’t happen if we restrict the environment more than is optimal. Lawmaking, like parenting, is about balance. We want to keep people from harm but don’t want to do so in a way that constrains behavior unnecessarily or more than is appropriate. Another way to think about it is more acute harm, in the context of safety. I chair an Internet Safety Technical Task Force, formed by 49 attorneys general and MySpace, in which tech companies are coming together to try and figure out how to use technology to keep kids safe online. The thing I’m most concerned about is a situation where no one is helping young people, or doing so much that you push them out into less safe environments. New environments in computing are created once a month. Why do young people go to Facebook? They don’t want to be in the other public spaces we’ve created. What I’m worried about is if we say MySpace and Facebook are unsafe or otherwise constrain those environments so they’re unpalatable or boring, young people will go to other spaces that are less safe.

What kind of response are you getting to your books? Are lawmakers interested?

Palfrey: ‘It’s grown up, so act that way!’

Zittrain: Exactly – ‘It’s grown up and it’s time to act responsibly.’

Palfrey: Both of our books are about teenager-hood and what’s great about being a teen.

Zittrain: I want the youthful, informal aspects of our information technology, but I also realize it’s the 21st century. You can’t just have a framework designed for people who would rather build their own clock than buy one.

Unlike when it first came out, the iPhone now allows some outside software to be added onto it. Did that happen because you and others complained that the first version was too closed?

Zittrain: Oh, I doubt it. I haven’t heard from anyone at Apple. The iPhone isn’t an evil plot, it’s an artifact of our times. But the question is, Does it point the way for the whole ecosystem? Google is coming out with a phone that anyone can write code for. You would think, ‘That’s great, Zittrain will put his money on that one.’ And yet I think, ‘I can’t believe it’s 1977 all over again!’ You put a phone equipped like the original Apple II out in 2008 and how soon before you go to the wrong site and your phone is fried, it’s sending spam, all the stuff that’s going on with PCs? People will tolerate that for about 10 seconds. So I’m worried.

Who shares responsibility for keeping the best of the Internet while addressing these valid concerns?

Palfrey: In most cases, the young people themselves are in the best position to solve the problems. Our book talks about concentric circles, where you start with the young people, and as you go rings out, parents are next because they have the trust of, and access to the young people, and teachers and mentors have important roles, then tech companies. I’d push social network sites like MySpace and Facebook into this category. They can do a lot and can use technology a lot. And we should consider the law. There are a few places where the law should be changed and could help. But that should be the last resort and not the first, and I say that very respectfully as a lawyer who believes deeply in the power of law to organize our society.

Why should law be the last resort in this environment?

Palfrey: At a time of extremely rapid change, adopting a new and specific law is very hard to do in a way that will in fact achieve your public policy objectives – if at all – for very long. The U.S. Code is riddled with things like the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992, which was seeking to regulate a particular technology, digital audio tape, which never took hold. So we’ve got these weird parts of the law that were relevant for 10 minutes — or never. And there are much worse examples. Jonathan and I have written a book on Internet censorship, Access Denied. You can look across the world and see laws that were meant to address what may have been real problems but which have much greater ramifications that anyone who passed them could have imagined.

One of the issues John raises in Digital Natives is digital overload, including multitasking. Can students – including law students — really absorb information when they’re doing two or five things at once? If not, how do you stop them?

Zittrain: The studies are pretty clear that multitasking doesn’t work. In my first-year torts class, I don’t allow laptops. On the other hand, one of the things I’ve been working on over the past several years are low bandwidth, light-weight teaching tools, so it’s, ‘Here’s something you can do online in the classroom.’ It’s called the Question Tool, and it allows students in class, as class is unfolding, to ask questions. Their questions go up online, on screen, and if it gets enough positive response from the other students, it gets injected into class itself – and students can answer each others’ questions on the fly. That’s been a lot of fun, and helped make class sessions more productive, especially when there are varying levels of expertise, and comfort with spoken English, in the room. So let’s make [multitasking] topical and relevant, and we can make [classroom learning] better than without it. A law school is a fabulous place to think about this, since so much of the enterprise is to teach people in a participatory fashion, where you’re part of the team – not, this is the law, here’s what you need to obey.