Supreme court justices have heard weighty oral arguments in the Ames Courtroom over the years, but the cases have been fictional, penned by legal thinkers expressly for the Ames Moot Court Competition. So it was an unprecedented occasion in February when the three justices of the Navajo Nation Supreme Court came to Ames to hear Navajo Nation v. Russell Means, a real case, dealing with issues of Navajo Common Law and equal protection under the U.S. Constitution, the power of Congress to regulate Indian affairs, and the jurisdiction of Navajo courts.

The defendant in the case was Russell Means, the high-profile American Indian Movement activist-turned-Hollywood-actor. Means, a member of the Oglala Sioux Nation who was married to a Navajo woman at the time of the alleged crime, was charged in 1997 with assaulting his then father-in-law, a member of the Omaha tribe, and another, Navajo man. Means took his case to the Navajo Nation’s high court, challenging the authority of the Nation’s Chinle District Court to prosecute him.

Seated in the Ames Courtroom beneath the flag of the Navajo Nation, Chief Justice Robert Yazzie, Associate Justice Raymond Austin, and Justice-designate Irene Toledo heard first from Means’s attorney, John Trebon, who argued that under the terms of the Treaty of 1868, the Navajo Nation does not have criminal jurisdiction over non-member Indians. Trebon further argued that Congress created an unconstitutional racial distinction between Indians and non-Indians in its 1991 legislation giving tribes the power to prosecute non-member Indians such as Russell Means, while non-Indians remain outside tribal criminal jurisdiction. In the 1991 legislation, Congress overruled – without the authority to do so, according to Trebon – the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1990 decision in Duro v. Reina, which had denied Indian tribes the right to exercise criminal jurisdiction over Indians from other tribes. Treating non-member Indians and non-Indians differently violates the Constitution’s Equal Protection clause, Trebon said.

[pull-content content=”Indian Law Study at HLSStudents who want to study Indian law can now choose from courses including Federal Indian law, Indigenous Peoples in International Law, and Tribal Legal Practices, offered this year for the first time and taught by Professor Leroy Little Bear of Harvard University’s Native American Program. In addition, through a new clinical project this spring, HLS students and University of Arizona College of Law students collaborated on the development of a sovereignty model treaty for the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council of British Columbia. The project was supervised by Professor Joseph Singer ’81 and University of Arizona College of Law Professor Robert Williams ’80, who notes that %DQUOTE%Harvard has vaulted into a leading position in Indian law, offering as many courses and clinical components as major law schools in the heart of Indian country.%DQUOTE% In January Williams returns as visiting professor to teach Federal Indian Law, this time with a new clinical component – a two-week Navajo Supreme Court clerkship. Fundraising is underway for an endowed visiting professorship in Native American Legal Studies, an effort Assistant Dean for Academic Affairs Alan Ray says reflects %DQUOTE%the School’s growing prominence as a leader in Indian law, and Dean Clark’s recognition of the importance of Indian law in American legal culture.%DQUOTE%” float=”left”]

The Navajo Nation’s acting chief prosecutor, Donovan Brown, said that Means consented to the jurisdiction of the Navajo Nation by marrying a Navajo and by conducting business that led to benefits from the Navajo Nation. In arguing that from time immemorial Navajos have had jurisdiction over non-Navajos who commit illegal acts in Navajo country, Brown drew on Navajo legend – a frequent practice in Navajo Court proceedings according to Chief Justice Yazzie – recounting the parable of two Navajo cultural heroes, twins named “Monster Slayer” and “Born for Water.” The twins appealed to the creator, Father Sun, for assistance against non-Navajo “monsters” who were attacking Navajos and Anasazi Indians. The twins’ appeal was answered with a gift of weapons to protect their people, which Brown said “demonstrates the creator’s grant of jurisdiction to Navajos over non-Navajos.” He also claimed that Congress did in fact have the right to overrule the Supreme Court in the Duro case.

According to Indian law expert Professor Joseph Singer ’81, in deciding the case, “the Navajo Supreme Court faces an almost impossible task. It must enforce law in a jurisdictional framework that splits power between tribal, federal, and state governments, and which does so in inconsistent and often unpredictable ways. At the same time the Court must remain true to Navajo traditions.” Singer predicts that regardless of the Navajo Nation Supreme Court’s decision, the issue of whether an Indian tribe can arrest and criminally prosecute a member of another Indian tribe will likely be heard eventually by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Indian Country Comes to Harvard

Since Robert Yazzie became chief justice of the Navajo Nation’s Supreme Court in 1992, he has welcomed opportunities for his court to sit at law schools, to demonstrate its workings, and to discuss the future of Indian judicial systems, whose legitimacy he says is constantly questioned. The court has visited ten schools, including Stanford Law School, the University of Michigan Law School, the University of New Mexico School of Law, and HLS. “Some of the best legal minds in the country are at Harvard,” says Yazzie. “The students are future leaders. The more we can inform them about Indian law issues, the better.”

Plans for the HLS event were set in motion last spring, when Robert Williams ’80, of the University of Arizona College of Law in Tucson and a 1999 Winter Term HLS visiting professor, approached Yazzie at an Indian law conference in British Columbia and asked if the justice would be interested in having his court come to HLS. Yazzie liked the idea, so Williams proposed it to Dean Robert Clark ’72, who responded enthusiastically. Williams, a member of the Lumbee tribe who during his student days was the only Indian at HLS, applauds Dean Clark for “bringing Indian country to Harvard.” The justices selected the Means case because of its important implications for the sovereignty of Indian law.

A Primer on Navajo Law

[pull-content content=”News FlashAs this story was completed, we learned that the Navajo Nation Supreme Court had decided in Navajo Nation v. Russell Means that the Nation’s Chinle District Court did have jurisdiction over Russell Means. %DQUOTE%We trust and hope that our decision will be honored as being in the interests of the Navajo People,%DQUOTE% said Chief Justice Robert Yazzie.” float=”right”]

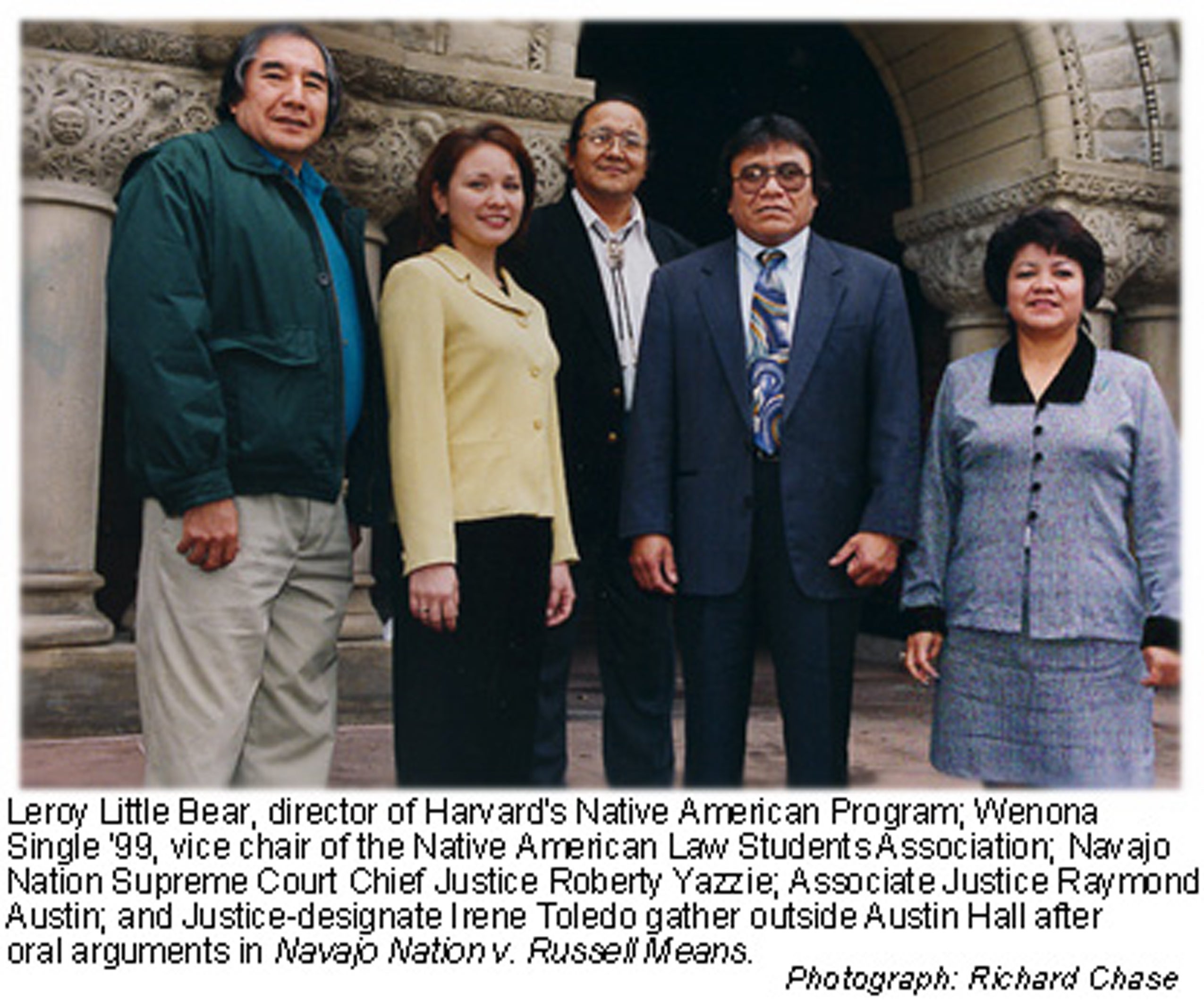

At a Friday evening program before Saturday’s oral arguments, Dean Clark told Indians and non-Indians who packed the Ames Courtroom that the visit by the Navajo Nation Supreme Court “exemplifies the School’s commitment to the study and understanding of Native legal systems,” and named expanded opportunities for HLS students to study Indian law. Harvard University Provost Harvey Fineberg also spoke, and Leroy Little Bear, director of Harvard University’s Native American Program and a member of the Blood Tribe of the Blackfoot Confederacy, sang a song in his native language to honor the Navajo justices. Wenona Singel ’99, vice chair of the Native American Law Students Association, introduced the justices, who gave an overview of their court system, the largest among some 150 Indian court systems. Its seven district courts handled over 65,000 cases in 1998, with the Supreme Court, in Window Rock, Arizona, hearing 151 cases.

Forty years ago, the Navajo Nation Council, the tribe’s legislative body, created the current Navajo court system, modeled on the American system, Chief Justice Yazzie told the audience, “partly so the outside system would stay away.” Throughout his remarks Yazzie emphasized the importance of Navajo Common Law, explaining that “living legends” such as the story of Monster Slayer and Born for Water form its foundation. In the mid-1980s, the Navajo Nation Supreme Court renewed its commitment to making Navajo Common Law “the backbone” of Navajo law, said Yazzie, adding that he and Justice Austin are working on a Navajo Common Law curriculum, based on an oral history project they are conducting with Navajo medicine people.

Remarking on some of the most far-reaching efforts by white people including a noted nineteenth-century Harvard Law professor – to exert legal control over Indians, Yazzie said the Courts of Indian Offenses were established by the U.S. government in 1883 as a means “to civilize Indians and abolish Indian Common Law.” Shortly thereafter, James Bradley Thayer, an HLS constitutional law professor and president of the influential New York organization Friends of the Indians, declared that the Courts of Indian Offenses were inadequate to “civilize” Indians and supported U.S. plans to further increase legal control over Indians.

Despite two centuries of U.S. efforts to undermine tribal sovereignty – including the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions in Duro and other cases concerning Indian self-governance – today the Navajo courts are firmly established, Yazzie said. Navajo Common Law and statutory laws are the laws “of preference.” When no Navajo or federal law covers a case, state law may be invoked. The courts have both adjudicative and legislative jurisdiction over Indians and non-Indians in civil cases. They have criminal jurisdiction over Indians, but not non-Indians – except those who assume tribal relations with Navajos – in criminal cases and the authority to impose jail sentences of up to six months. Major crimes are subject to U.S. federal jurisdiction, unless both victim and perpetrator are non-Indian, in which situation the state has jurisdiction.

Judges, of whom there are 14, half of them men and half women, are appointed by the Navajo Nation Council and serve two years of probation before they are eligible for a lifetime appointment. They must have in-depth knowledge of federal and state laws as well as Navajo law and the laws of other tribes, Yazzie explained, and must be fluent in the Navajo language so that older Navajos, many of whom do not speak English, can understand court proceedings.

Peacemaking, at the heart of Navajo Common Law and “the first process Navajo people used to settle disputes,” according to Yazzie, is an integral part of the court system. Family court judges may refer cases to peacemakers at their discretion. “Everyone affected by the conflict comes together with the peacemaker,” to work out a mutually satisfactory solution, and “to restore stability in the lives of both the defendant and the victim,” Yazzie told the gathering, adding that a study shows the Navajo people prefer peacemaking to family courts.

Efforts to expand peacemaking – today there are 225 peacemakers – are a hallmark of Yazzie’s tenure as chief justice and part of the Navajo Nation’s commitment “to return to local communities greater control so they can solve their own problems.” About 15 cases were referred to peacemaking in 1992, Yazzie’s first year as chief justice. Since then peacemakers have helped settle 1,300 cases. Yazzie said that he has had the opportunity to share his experience of peacemaking around the world, in Bolivia, Canada, South Africa, and elsewhere.

Toward the Future of Navajo Justice

In an interview with the Bulletin after the Harvard visit, Chief Justice Yazzie discussed challenges facing the Navajo justice system and his priorities as chief justice.

Citing a 1999 Department of Justice report, Yazzie noted that crime rates in Indian country are higher than in the rest of the United States, and said poverty and inadequate crime prevention resources are among the main causes. The 65,000-plus cases that came before Navajo Nation courts last year included more than 21,000 criminal cases. Driving while intoxicated ranks high, as do crimes against persons, including family violence. Noting that half of the population of over 250,000 Navajos is under the age of 20, Yazzie said the Navajo Nation faces a serious gang problem: “If we don’t do something, children will be caught up in the cycle of violence. The Navajo Nation needs an integrated approach to crime prevention and criminal enforcement, including social programs, especially for youth, as well as more police and resources for our court system.” Yazzie was recently in Washington, D.C., with leaders of the Navajo Nation Council to make the case for more resources to U.S. legislators.

Criminal enforcement is one of the most difficult problems tribal governments face, Yazzie emphasized. Federal and state government officials notified about crimes under their jurisdiction are often unresponsive, especially when the crime occurs in a remote area of Indian country, and are lackadaisical about prosecution. In the past four years, some 10,000 crimes were committed by non-Navajos on Navajo reservations. “Many crime victims live miles from federal courts. The state doesn’t want to deal with them, and neither do the U.S. attorneys.”

Yazzie noted his commitment to increasing community control in the administration of justice. In 1994 he initiated a sentencing commission authorizing judges to sentence offenders to community service as an alternative to incarceration. The commission is part of his larger vision for the Navajo Nation courts, he said. “The U.S. government has always told us that we should resolve our disputes by American methods. The American way is to establish authority, to wear black robes and have extensive rules of law and systems of punishment. That is a very expensive system, and it takes power away from the communities. We are trying to help local communities resolve their own problems. Alternative sentencing is one way, and peacemaking is another. The age-old process of peacemaking, he added, “is not ‘ADR,’ it’s ‘ODR,’ original dispute resolution.”