Mentorships between Harvard Law School professors and the students who followed them into academia have taken many forms over the course of two centuries. In some instances, it’s even possible to trace a kind of intellectual lineage that connects contemporary scholars on the faculty to forebears who taught at HLS in its first century.

As seen in the stories on the following pages, some first encountered the professors who had the most influence on their subsequent careers on the first day of class; other mentorships didn’t ripen until years after graduation.

Some followed paths into identical areas of law, while many learned more about how to think about legal scholarship or teaching than they did about any particular subject.

Some have become lifelong friends or, in the case of one pair of faculty colleagues, intellectual adversaries.

Some have returned to Harvard’s faculty, and many more have gone on to teach elsewhere, some of those eventually assuming deanships at the nation’s other top law schools.

Together, they have influenced the direction of legal doctrine and shaped the course of American legal education.

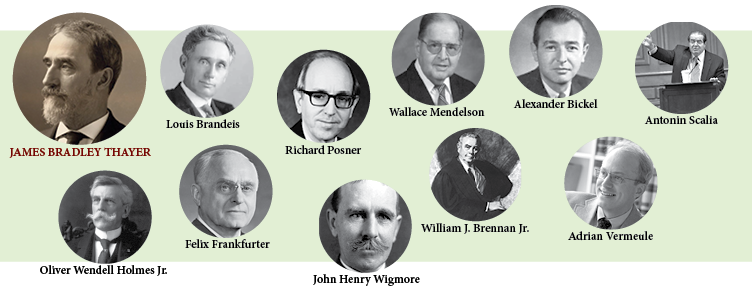

The school and Thayer

No professor can claim deeper family ties to the Harvard Law School faculty than James Bradley Thayer LL.B. 1856, who taught at the school from 1874 to 1902. His son served as the school’s third dean between 1910 and 1915, and his grandson was also later a faculty member.

His theory of judicial restraint proved to be an even more lasting intellectual legacy, one that influenced a trio of interconnected alumni who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for much of the 20th century.

In their own ways, Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. LL.B. 1866, Louis Brandeis LL.B. 1877 and Felix Frankfurter LL.B. 1906 all became adherents to the “School of Thayer,” as Richard Posner ’62, the recently retired federal appeals court judge, called it in a 2010 lecture.

Thayer first laid out his theory that judges should invalidate laws only if their unconstitutionality is “so clear that it is not open to rational question” in an 1893 article in the Harvard Law Review. (This was far from Thayer’s only contribution to legal scholarship: His study of evidence paved the way for a treatise by his former student John Henry Wigmore LL.B. 1887 that’s still published today.)

“The bedrock upon which Holmes, Brandeis, and Frankfurter built their judicial philosophies.”

Thayer’s view of the judicial function “was the bedrock upon which Holmes, Brandeis, and Frankfurter built their judicial philosophies,” Wallace Mendelson ’36, a longtime government professor at the University of Texas, wrote in a 1978 law review article.

Holmes, who practiced with Thayer at a Boston law firm and overlapped with him briefly on the Harvard Law School faculty, later wrote that he “heartily” agreed with Thayer’s approach.

Brandeis studied under Thayer and helped Thayer collect materials for a new course he planned on constitutional law, according to a biography of Brandeis by Melvin Urofsky. Thayer later enlisted Brandeis to help convince Holmes to join the faculty. Holmes did so, but soon left to become a judge on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

Brandeis later taught Thayer’s evidence course when his former professor went on leave and did such a good job that the school offered him an assistant professorship, although he opted to stick with his legal practice, Urofsky recounts.

Frankfurter, who taught at Harvard Law School between 1914 and 1939 before joining the Supreme Court and was a close friend to Holmes and Brandeis, considered Thayer “the great master of constitutional law.”

By the time ill health forced Frankfurter to retire from the Supreme Court in 1962 after 23 years, many justices, including Chief Justice Earl Warren and Frankfurter’s former student William J. Brennan Jr. ’31, had abandoned even a pretense of adhering to Thayer’s notion of restraint.

Frankfurter, legendary for sending his former students to jobs in New Deal Washington, left a similar mark on Harvard Law School. At the time of his death in 1965, 11 professors then on the Harvard Law faculty either had served Frankfurter as clerks or had been chosen by him to serve in the chamber of Holmes or Brandeis, according to a Harvard Crimson obituary.

In the years that followed, it fell to one of Frankfurter’s former clerks, Yale law professor Alexander Bickel ’49, to carry the torch for Thayer’s ideas, most notably in his 1962 book, “The Least Dangerous Branch.”

At least one current faculty member—Adrian Vermeule ’93—still identifies with Thayer.

Vermeule’s principal focus was administrative law, but he became interested in statutory interpretation while clerking for Justice Antonin Scalia ’60, who “more or less ordered me” to do so, he said.

Vermeule argues in his first book for a strict version of the kind of deference advocated by Thayer, prompting Posner to label him a “neo-Thayerian.” Harvard Law School librarians put Thayer’s portrait in Vermeule’s office after he joined the Harvard Law faculty in 2006. The portrait still “hangs in the place of honor” in his office in Areeda Hall, Vermeule said.

‘He belonged on Mount Rushmore’

Laurence Tribe ’66 finds it fitting and “a little bit ironic” that he holds a professorship previously occupied by two of his mentors. Archibald Cox ’37 and Paul Freund ’31 S.J.D. ’32 both preceded him as Harvard’s Carl M. Loeb University Professor.

Freund, who taught at Harvard from 1939 to 1976, supervised Tribe’s third-year law school paper. Tribe also enrolled in Freund’s seminar in constitutional law.

Tribe, not yet 30, found it difficult to call Freund by his first name when he returned to teach at Harvard Law School a few years later. “He belonged on Mount Rushmore,” Tribe said.

Tribe wasn’t alone in holding in such high regard a professor whom former Harvard Law Dean James Vorenberg ’51 called “the leading constitutional law scholar of his time.”

Freund turned down offers by two presidents to serve as solicitor general. When he told President Kennedy he wanted to continue work on a Supreme Court history, Kennedy retorted he’d hoped Freund would “prefer making history to writing it.”

As a justice, Frankfurter relied on Freund, his former student, to pick all of his clerks, as did Justice Brennan at the start of his tenure on the Court. Tribe played a similar role for Justice Potter Stewart, for whom he’d clerked.

“The law and the nation have been most fortunate to have Paul Freund as a thinker and as a poet of the law,” Tribe said in 2007 at the opening of a law school library exhibit honoring Freund, noting his “gentle erudite wisdom and his wise and genuine erudition.”

Freund and Cox weren’t the only professors who influenced Tribe. He also credits Henry Hart LL.M. ’30 S.J.D. ’31, Paul Bator ’56 and Louis Jaffe ’28 S.J.D. ’32. Jaffe joined the faculty in 1950 and is considered a founder of modern administrative law.

She was ‘the most extraordinary student’

Kathleen Sullivan ’81 credits her mother for introducing her to Tribe and a former Harvard faculty member who later served as a mentor: Susan Estrich ’77.

Sullivan’s mother sent her an ad for the first edition of Tribe’s treatise when she was studying at Oxford as a Marshall Scholar, with a note remarking that the book might be helpful before law school. Her mother also sent her a Time magazine story on Estrich’s election as the Harvard Law Review’s first female president.

She loved the book and was eternally grateful that she wound up assigned to Tribe’s constitutional law class her second year. “I marveled at this brilliant man who spoke in perfect paragraphs and seemed to bring a new level of elegance to any topic,” Sullivan said.

Tribe enlisted her help on a Supreme Court brief the following year.

“Her sense of the most persuasive way to cast the issues and her rhetorical command were remarkable.”

“Her sense of the most persuasive way to cast the issues and her rhetorical command were remarkable for any lawyer, much less a student,” Tribe recalled.

He described Sullivan as “the most extraordinary student I had ever had,” the sort of effusive praise he has since offered for another student who also subsequently taught constitutional law, at least part time: former President Barack Obama ’91. (Tribe also points proudly to two of his former students who’ve joined the Court: Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’79 and Justice Elena Kagan ’86.)

That first case proved to be one of many such collaborations between Tribe and Sullivan, including one in 1983 that pitted them against Estrich, who was so impressed by Sullivan that she vowed they would never be on opposing sides again. They became fast friends, Estrich told the Los Angeles Times in 1999.

Estrich was teaching at Harvard Law School at the time and set out to get Sullivan hired there as well, enlisting her contacts and coaching her protégé about presentation. “I had been in law teaching … long enough to see enough women come through and fail to generate excitement because we don’t know how to be commanding in this world,” Estrich told the Times.

Sullivan joined the Harvard Law faculty in 1984 and stayed until heading for visiting professorships at USC and Stanford, where she moved permanently in 1993.

She told the Los Angeles Times that getting out from under Tribe’s shadow was perhaps an unconscious part of the West Coast’s appeal: “[H]ere on the West Coast, I have just been Kathleen Sullivan. I haven’t been Kathleen Sullivan, comma, protégé of Laurence Tribe.”

Nevertheless, Sullivan said having Tribe as a mentor had been “crucial,” and she credits him with showing every dimension of what’s “wonderful about this job.” “To study with Larry then become his research assistant and his colleague in litigation and later his colleague on the Harvard Law faculty has been one of the greatest joys and privileges of my life,” she said.

Sullivan became Stanford’s first female dean in 1999, succeeding another constitutional law scholar, Paul Brest ’65. In 2005, Sullivan joined the law firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart, building a practice as one of the nation’s top appellate advocates. (The firm also recruited Estrich in 2008 and then added Sullivan’s name to its moniker in 2010.)

Tribe and Sullivan reunited—this time as adversaries—as part of Harvard Law School’s bicentennial celebration in October, taking opposite sides in a reargument of the landmark case Marbury v. Madison.

A ‘complicated’ relationship

Randall Kennedy admits he had a “complicated” relationship with Derrick Bell, whom he considers “a mentor, colleague, friend and adversary.”

Bell, Harvard Law School’s first tenured African-American professor, had left the school temporarily by the time Kennedy joined the faculty in 1984.

Kennedy began teaching the course Bell had previously taught on race relations and law. (Among those who helped ease his transition was Duncan Kennedy, who shared long walks with Kennedy around Cambridge, talking over contracts law and race relations.)

Bell and Randall Kennedy didn’t meet until 1986, when Bell returned to Harvard after serving as dean of University of Oregon School of Law, although they had followed each other’s scholarship closely.

After all, they “tilled the same soil” intellectually, albeit from very different perspectives, Kennedy said. They differed in private about law school hiring decisions and quite publicly in an unusually pointed volley in reviews of each other’s books.

Bell said Kennedy took positions “that render him an apologist on aspects of the criminal justice system,” despite “the threat they pose for all blacks.” Kennedy said Bell’s defense of Louis Farrakhan represented an “egregious toleration of bigotry.”

“He and I dealt with similar subjects, race relations law. Sometimes we agreed, sometimes we disagreed—sometimes rather sharply,” Kennedy said. “But I think the disagreements have been productive for me. Having to be pushed to explain why I disagree with him was important, so he certainly is an important person in my development here as an ideological adversary.”

Even as they disagreed publicly, Kennedy said he and Bell came to share “a mutual and quite profound set of tragedies that drew us together even while ideologically we were apart.”

Bell’s wife, Jewel, was diagnosed with breast cancer and consulted with Kennedy’s wife, Yvedt, who was a breast cancer surgeon. Bell’s wife died in 1990; Kennedy’s wife later died of melanoma.

Bell and Kennedy partially reconciled at the end of Bell’s life. Kennedy phoned when he first heard Bell was ill. Bell called a few weeks later to ask Kennedy to teach a session of his seminar at NYU School of Law, where he’d taught since 1990. Kennedy taught the class a week after Bell died in 2011.

Kennedy recently finished an essay about Bell, motivated by a sense that he hasn’t gotten his proper due from overly “hagiographic” admirers or “dismissive” critics.

His research has deepened Kennedy’s appreciation for Bell and what he’d experienced as Harvard Law School’s first tenured African-American professor.

“Places like this weren’t used to black professors.”

“Places like this weren’t used to black professors. For God’s sake, with all the tumult, all the cross-cutting pressures, I’m sure it was very difficult for him,” Kennedy said. “I’m sure he had to contend with lowered expectations. I’m sure he had to contend with condescension, all sorts of things, and in my view he did contend with those things.”

Georgetown law professor Sheryll Cashin ’89 considered Bell, Kennedy and Charles Ogletree ’78 all mentors during law school. But it is Kennedy who influenced her the most—and whose career hers has paralleled most closely.

Like Kennedy, Cashin clerked for Justice Thurgood Marshall after graduation. (Bell worked on school desegregation cases at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund with Marshall, who was recruited there by his own mentor, Charles Hamilton Houston ’22 S.J.D. ’23.)

She has taught a course at Georgetown similar to Kennedy’s on race, racism, and American law and has written on similar topics, such as affirmative action and interracial intimacy.

“Randall Kennedy inspired me, by his own example, to be brave and just write what I wanted to write in the format I wanted to write it in, which is books for a larger audience,” Cashin said. “I didn’t have many models other than him for doing what I wanted to do. I can’t thank him enough.”

In 2004, The New York Times ran a review of Cashin’s book on the legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education decision that also reviewed books on the same subject by Ogletree and Bell.

Cashin said she considers all three “wonderful role models” who taught her that academics have “an obligation to use this platform and this voice to help others and help the community and be socially relevant.”

“All of them did that in different ways,” Cashin said.

A mentor’s persistence: ‘Maybe I am interested’

Elizabeth Bartholet ’65 had no interest the first time—or the many that followed—that Professor James Vorenberg ’51 broached the idea of joining the Harvard Law School faculty.

Bartholet was happy with her public interest career, one that Vorenberg had tracked since she’d been a student in his criminal law class.

Bartholet went to work for Vorenberg after a clerkship when he served as executive director of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice.

Vorenberg helped her get “in the door” for an interview at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund by introducing her to Jack Greenberg, its director-counsel. She wound up working there for five years.

He also introduced her to Herbert Sturz, the founding director of the Vera Institute of Justice, where she went to work in 1972 in order to start a new public interest law firm focused on helping ex-offenders and ex-addicts fight discrimination and gain access to jobs and treatment. She then left Vera to run this firm, the Legal Action Center.

It was during this time that one of Vorenberg’s former law school professors offered him the part-time job he would become most famous for beyond Harvard Law’s campus. Archibald Cox ’37 hired him as his principal assistant in the Watergate Special Prosecutor’s Office.

All the while, Vorenberg continued to stay in touch, calling Bartholet once a year to see if she might want to move to academia. She kept telling him she had no interest. “But at a certain point, after running Legal Action for five years, I thought, Maybe I am interested,” she said. “I called Jim and he set up an interview.”

Bartholet started teaching at Harvard Law School in 1977 and was granted tenure in 1983, two years after Vorenberg became dean. She was the first woman on the assistant professor track to gain tenure in the law school’s history.

“He was an incredibly important adviser, mentor and friend over the years,” Bartholet said.

‘The model of … the person I wanted to be’

Carol Steiker ’86 graduated from law school just seven years after the professor she has considered her mentor while she was a student and throughout the three decades since: Martha Minow.

Minow, who joined the Harvard Law faculty in 1981 after completing a clerkship with Justice Thurgood Marshall, taught Steiker family law and later supervised her third-year paper.

In between, Steiker, her friend Elena Kagan ’86, and another classmate asked Minow to join their informal reading group on law and literature inspired by an article by Judge Richard Posner ’62 on culture and the law. (The small reading group that met outside on the lawn would ultimately produce three Harvard Law School professors, the school’s first two female deans, and the nation’s first female solicitor general and fourth female Supreme Court justice.)

Steiker came to law school thinking she wanted to be a professor, a goal affirmed during a conversation in Minow’s office on the third floor of Griswold Hall in which she asked whether Minow enjoyed being a law professor.

“I remember the way her face lit up and she said, ‘I love it,’” Steiker said. That was a time when Harvard still had less than half a dozen women professors, and she said, “That was very affirming to me of what I wanted to do, and she was the model of the kind of career I wanted to have and the person I wanted to be.”

Minow continued to be a “wonderful mentor” when Steiker returned as a professor in 1992, although she chose a different academic focus: criminal law and the death penalty, inspired in part by her time as a clerk for Justice Marshall. Their connection continued after Minow became dean, and she supported Steiker’s efforts to build the Criminal Justice Policy Program, which she co-directs with Alex Whiting.

Some of Steiker’s former criminal law students are now teaching the subject themselves on the faculty, including Jeannie Suk Gersen ’02 and Ronald Sullivan ’94.

No student has followed in Steiker’s footsteps more closely than Andrew Crespo ’08, who took her advanced criminal law class and worked as her research assistant. She invited Crespo to attend the oral argument for a pair of Supreme Court cases they’d worked on together. “The way she included me in that was really special,” Crespo said.

Like Steiker, Crespo also served as president of the Harvard Law Review—in his case, the first Latino ever to do so.

Like Steiker, he also worked as a public defender and clerked on the Supreme Court—he clerked for Kagan and Justice Stephen Breyer ’64—before joining the faculty in 2015.

Steiker and Minow championed his hiring although he wasn’t even formally on the academic market.

“I feel really fortunate to have her as a mentor, friend and colleague,” Crespo said of Steiker.

Crespo said he models his classroom style on former Professor Elizabeth Warren, who taught him contracts a few years before her election to the U.S. Senate in 2012 took her to Washington.

“I do try to call on 40 students per class and keep this multi-threaded conversation going, and I think I have the confidence to try to do that because of the experience I had learning that way with Elizabeth Warren.”

What it means to be a great teacher

Professor Steven Shavell began guiding Crystal Yang ’13 before she even applied to law school.

Yang was a Ph.D. student in Harvard’s economics department and first got to know Shavell as his research assistant.

“He said, ‘I think you might have a skill that could be very valuable if you combine law and economics,’ and he encouraged me to apply to law school in the first place,” she said.

Shavell similarly started out as an economics professor in 1974 before joining the law school faculty in 1980.

Yang took Shavell’s economic analysis of law class and a seminar on law and economics he co-teaches with Louis Kaplow ’81. (Kaplow and fellow law and economics professor Lucian Bebchuk LL.M. ’80 S.J.D. ’84 were also students of Shavell’s.) Yang was also a student fellow at the John M. Olin Center for Law, Economics, and Business, which Shavell founded in 1985 and directs.

Yang came to focus on applying empirical analysis to criminal law, which Shavell supported. “Steve is encouraging of using the tools of law and economics in every single field,” Yang said. “He’s written in criminal law, torts, contracts, for example. He’s supportive no matter what you do.”

“You can trace so many generations of law and economics scholars to Steve.”

He has been a “consistent mentor” for Yang at every stage of her career, as she first applied for academic jobs and then after she joined the HLS faculty in 2014 as an assistant professor, continuing to read and provide detailed feedback on every paper she has written.

“You can trace so many generations of law and economics scholars to Steve,” Yang said. “When he mentors law students, he makes a lifetime commitment to doing so.”

Shavell played a similar role in the academic career of NYU law professor Marcel Kahan ’88, who was his student when law and economics was still an emerging field a quarter century ago.

“It was Steve and the class that he taught and work I did as his research assistant that really piqued my interest and really put me in a position that I was able to get a job,” said Kahan, who also considers Kaplow and Bebchuk mentors.

Yang said she looks to Shavell as a model in her own career. “He’s really set an example of what it means to be a great teacher and that your commitment to your students does not end when class is over,” she said.

‘Grandfather in the law’

Yale law professor Harold Koh ’80 isn’t exaggerating when he calls Louis Sohn LL.M. ’40 S.J.D. ’58 his “grandfather in the law.”

Koh’s father, Kwang Lim Koh LL.M. ’52 S.J.D. ’55, wrote his doctoral dissertation under Sohn in the early 1950s before becoming the first Korean law professor in the United States and serving as South Korea’s envoy to the United States and United Nations. Twenty-five years later, Koh and his sister, Jean Koh Peters ’82, who is also a Yale law professor, studied under Sohn.

Sohn was a magnet for foreign students such as Koh’s father due, in part, to his own experience as a Jewish refugee from Poland. Sohn arrived at Harvard Law School at the age of 25, two weeks before the start of World War II, at the invitation of a professor who’d read one of his treatises.

Sohn served six years as a research assistant to his mentor, Manley Hudson LL.B. 1910 S.J.D. 1917, who taught international law at Harvard from 1919 until 1954. Together, they helped write the framework that created the United Nations Charter and the statute establishing the International Court of Justice.

Hudson started teaching international law at a time when it “was hardly accepted as a fit subject for law schools,” and lived “to see it become an essential part of legal education,” in large part through his efforts, Dean Erwin Griswold ’28 S.J.D. ’29 said in a tribute after Hudson’s death in 1960.

“In a very real sense, the program of International Legal Studies not only at Harvard Law School but elsewhere in the world is his monument,” Griswold said.

Sohn later succeeded Hudson as the Bemis Professor of International Law and as the elder Koh’s thesis adviser after his mentor’s retirement. In the course of a 35-year career at Harvard Law School, Sohn taught an early course on the U.N. “because nobody else would teach anything so crazy,” as he recalled in a 1977 interview, and served as a delegate to a 1977 conference that drafted the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

A few years later, Koh and his sister reconnected with their father’s mentor as law students, sharing lunches at a Harvard Square Chinese restaurant where Sohn invariably ordered the kung pao chicken with pignolia nuts.

Koh never took Sohn’s class (his sister did), although he wound up focusing on international law in a career that’s included stints as the dean of Yale Law School and as the U.S. Department of State’s chief legal adviser.

Koh’s work often involves law of the sea issues. “Never for a second do I do it without thinking of my dad and Professor Sohn,” he said.

David Kennedy ’80, the Manley O. Hudson Professor of Law, took all of Sohn’s classes that fit in his schedule and served as his research assistant while studying for the bar in Cambridge (Sohn was in Geneva).

Kennedy never got to know Sohn very well, and it wasn’t until much later that he learned about the pivotal role his professor played in his career.

Sohn had recommended Kennedy for appointment to the Harvard Law faculty without ever mentioning it to him.

“It’s not always the people you sit around having coffee with that do what’s needed for you to become successful,” Kennedy said. “I wouldn’t be here if he hadn’t done that.”

Kennedy does his part to mentor future generations of international professors, bringing 100 young scholars together each year for a workshop under the auspices of HLS’s Institute for Global Law & Policy.

Stern professor, lifelong mentor

In the fall of 1955, Arthur Miller ’58 was just a frightened 1L rather than the classroom colossus he later became teaching for 36 years at Harvard Law School.

That’s when he enrolled in the civil procedure course taught by Benjamin Kaplan, the “stern and demanding” professor who Miller said became his “mentor and role model, not simply in law school but for the better part of my professional life.” Kaplan invited Miller to be his summer research assistant after reading a memo Miller wrote on the deficiencies in the Harvard Law Review’s copyright practices. They spent weekends discussing copyright law revisions while digging for clams and picking blueberries on Martha’s Vineyard.

Kaplan again enlisted Miller after graduation, even getting him released from military duty for a weekend to work on a revision to “Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.” Kaplan convinced Chief Justice Earl Warren to write Miller’s commanding officer that his absence was in furtherance of the nation’s business.

Their relationship continued as Miller joined Harvard’s faculty in the early 1970s and Kaplan left to become a justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

“After more than 50 years of teaching his subjects—civil procedure and copyright—there is only one answer I can give to the question he asked me repeatedly over the years (as if asking it of himself), what was I going to do when I grew up?” Miller wrote in a tribute after Kaplan’s death in 2010. “Time has made the answer clear. It has been to try to follow in his footsteps and to be a mentor to others as he was to me.”

No relationship with a student has meant more to Miller than the one he formed with John Sexton ’79, who enrolled in law school at the age of 33, already a tenured professor of religion.

Miller’s civil procedure class was Sexton’s first at Harvard, and it was also where he met his wife, Lisa Goldberg ’79.

“People who are willing to share the spotlight … are too rare in this world.”

In Sexton’s second year, Miller asked him to teach his first-year civil procedure class for two weeks in his absence. That opportunity—which Miller repeated in Sexton’s third year—helped launch Sexton’s career as a civil procedure professor. Miller later asked Sexton to co-write a revision of his casebook.

In 2007, after Sexton had become dean of NYU’s law school and then president of NYU, he helped lure Miller to teach there full time, a move Sexton calls “a dream come true.”

“People who are willing to share the spotlight or indeed turn the spotlight away from them to others are too rare in this world, and he’s one of them,” Sexton said.

‘I could only hope to be half as good’

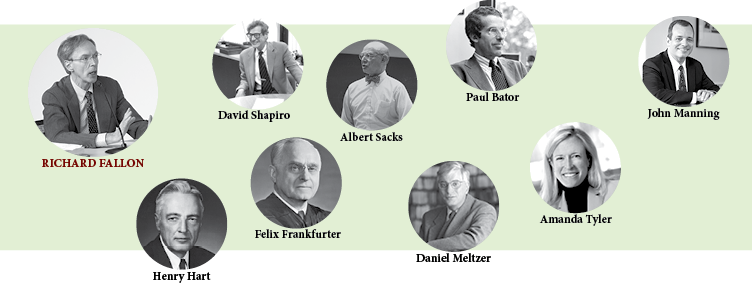

Richard Fallon had perhaps absorbed too well his alma mater’s approach to thinking about the law before joining Harvard’s faculty in 1982 just two years after graduation.

“When I was in law school [at Yale], some of the professors who influenced me most had a tendency to start theorizing at 30,000 feet and then gradually move downward and frequently, never totally make contact with the earth,” Fallon said.

It was his colleague Professor David Shapiro ’57, whom Fallon turned to when he taught federal courts for the first time in the spring of 1983, who taught him how important it was to ground grand legal theories in the facts of cases.

“He’d say again and again, ‘Give me a case,’” Fallon recalled. “He wanted to be rooted in the concrete facts of some particular dispute to see if the theory was illuminating and helpful.”

Shapiro, who joined Harvard Law School’s faculty in 1963, was also a link all the way back to the roots of federal courts as a legal discipline at the school decades earlier.

The founding of the field is credited to Harvard Law Professor Henry Hart LL.M. ’30 S.J.D. ’31 and Herbert Wechsler of Columbia Law School, who first published their casebook on federal courts in 1953. They dedicated that first edition to Felix Frankfurter LL.B. 1906, whom they credited with first opening their eyes to these problems. Hart had studied in Frankfurter’s seminar on federal jurisdiction at Harvard Law School.

Shapiro took Hart’s class in the 1950s and went on to co-write five revisions of the Hart and Wechsler casebook. (Hart and another one of his former students, Albert Sacks ’48, produced their own set of teaching materials on the legal process.)

Fallon established a connection with another giant in the field immediately upon arriving at Harvard. He sat in and observed the federal courts course taught by Professor Paul Bator ’56, who was a co-editor of the casebook’s second and third editions.

Fallon himself has been working on the casebook since 1996 and, along with Daniel Meltzer ’75, dedicated the fifth edition to Shapiro.

Fallon and Meltzer both joined the Harvard Law faculty in 1982 and became close friends as they began teaching federal courts at the school at almost exactly the same time. No one affected the way Fallon thought about the topic more than Meltzer.

“Mentor relationships are terrific, but there can also be enormous benefit in having an exact contemporary who is struggling with the issues more or less at the same time and at the same stage of professional development,” Fallon said.

Meltzer died in 2015, and Fallon now has two former students as co-editors on the casebook’s seventh edition: Harvard Law School Dean John Manning ’85 and Amanda Tyler ’98, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, who was also a student of Shapiro’s.

Manning said he first began thinking about the role of the federal courts during Fallon’s class in the fall of his third year.

A link all the way back to the roots of federal courts as a discipline.

“That fascinated me and that got me interested in larger questions of proper institutional roles and the rule of law in a constitutional democracy, and it really set me on a new course,” Manning told the Harvard Gazette in a video at the time of his appointment as dean this year.

When Tyler decided to become a law professor, she was asked during interviews whether she had a model on which she’d draw in her teaching and scholarship. “The answer was obvious. I could only hope to be half as good as David,” she wrote in a 2006 Harvard Law Bulletin tribute.

He built something enduring

From the moment Gary Bellow ’60 joined the faculty as director of Harvard’s clinical program in 1972, his new colleagues recognized that he was unique.

“There aren’t a lot of Gary Bellows around the United States,” Professor Frank Sander ’52 told The Harvard Law Record at the time of his appointment. “It’s very hard to find people to integrate good clinical work with academic work of the kind Gary Bellow has done.”

In subsequent decades, Bellow and Jeanne Charn ’70—named an assistant dean in 1973—built Harvard’s unique model of clinical education, one that combines classes and placements that provide hands-on training to students and free legal counsel to those in need.

It is a model that not only survived Bellow’s death in 2000, but continues to thrive at Harvard Law School and far beyond, thanks, in part, to the generations of students they mentored.

One of the students he inspired most—David Grossman ’88—first found a professional calling when he was Bellow’s student and during his time at HLS’s Legal Services Center.

“He became my mentor and, in a sense, my hero.”

“He became my mentor and, in a sense, my hero—someone whom I sought to model my life after,” Grossman said in remarks at Bellow’s funeral. “And that was true not only of me but of literally hundreds of his former and current students who were similarly inspired by him.”

Grossman returned seven years after graduation as a clinical instructor and then served as managing attorney of the housing unit for 11 years before becoming director of the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau in 2006. (He died in 2015 of cancer at the age of 57.)

“It’s generation to generation,” said Dan Nagin, vice dean for experiential and clinical education and faculty director of HLS’s WilmerHale Legal Services Center. “Gary taught and mentored Dave, and Dave carried on that tradition and mentored others.”

Esme Caramello ’99, who served as Grossman’s deputy director at the Legal Aid Bureau, remembers how Grossman adopted Bellow’s model of using legal services to effect social change in response to the foreclosure crisis a decade ago.

Grossman collaborated with community partners to flood resources and change the expectations of the courts and bank lawyers who had grown used to getting orders to force tenants of foreclosed properties to vacate quickly.

“We did a bunch of these cases until the expectation changed to: The homeowner or tenant gets to stay or gets tens of thousands of dollars in cash to buy them out,” said Caramello, who is now faculty director of the Legal Aid Bureau and a clinical professor of law. “It was through the volume of targeted small cases that we achieved that cultural change.”

No faculty member had a greater influence on Bellow than Albert Sacks ’48, in whose course The Legal Process Bellow enrolled as a student, said Charn, who was married to Bellow for nearly three decades. Bellow later titled his book “The Lawyering Process” in tribute to Sacks. He was also instrumental in hiring both Bellow and Charn and helping build the clinical program while serving as dean between 1971 and 1981, Charn said.

Luz Herrera ’99 took the lawyering process course taught by Bellow and Charn. She said the related clinical work helped her find a practical application for the critical race theory that her law school mentors, Charles Ogletree ’78 and Lani Guinier, had exposed her to.

Herrera later reconnected with Charn when Herrera received the 2005 Gary Bellow Public Service Award for her work as a solo practitioner providing legal services in the underserved community of Compton, California.

Charn invited her to apply for a fellowship at the Legal Services Center, an experience that helped cement her interest in community development and ultimately led her to a career in clinical legal education.

“Jeanne is a mentor not just in clinical education; she’s a mentor in helping me navigate the entire system of legal services delivery,” said Herrera, who is now a professor of law and associate dean for experiential education at Texas A&M University.