Alumni remember the two presidential candidates as students

President Barack Obama ’91

This November, for the first time in the history of U.S. presidential elections, both candidates of the major parties are graduates of Harvard Law School.

Despite sharp differences in their politics, President Barack Obama ’91 and his Republican opponent, Mitt Romney J.D./M.B.A. ’75, share the HLS experience, though their times at Harvard were separated by nearly 20 years—and in the case of Romney, they included stints on the other side of the river as part of the joint-degree program that had recently been established with Harvard Business School (see story).

Mitt Romney J.D./M.B.A. ’75

Very smart, hard-working, decent, likable—many of the words used by their Harvard classmates to describe Obama and Romney are the same. But in other ways, the two are strikingly different, according to friends who knew them when they were students.

How did Harvard influence these two extremely driven and successful politicians? Who were they in school, and how does that compare with the candidates on the world stage today? Their classmates have this to say:

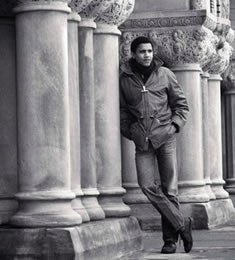

Barack Obama

While they might not necessarily have predicted that Barack Obama would become president of the United States, his former Harvard Law classmates, no matter their political persuasions, recognized him as especially gifted, and describe him as someone uniformly well-liked and respected, with an unusual maturity and wisdom that made him a natural leader.

Anthony Brown ’92, the lieutenant governor of Maryland, recalls that HLS in the early 1990s was a place of turbulence with student sit-ins and rallies protesting the lack of diversity among HLS faculty. While Obama supported the students, and gave a now famous speech at a rally in 1990, “Barack always had an insightful, reasoned kind of approach and advice,” says Brown. “Whenever he spoke, he left a lot of people in awe. We knew that he was going to do big things in his life, [although] I don’t know how many of us imagined he’d become president.”

“He was always somebody who just had an air about him of being a tremendously special guy.”

Steven Dettelbach

Steven M. Dettelbach ’91 is the U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Ohio. When asked today if he thought of Obama as headed toward the White House, Dettelbach says, “Of course you never think any real person you know is going to be the leader of the free world, but, if you went to our class at the time and told them somebody in this class is going to be president, and told them they were each allowed to write two names (and I say it’s two names because everyone will write their own name; after all, it’s HLS), many, many people would have picked [Obama]. He was always somebody who just had an air about him of being a tremendously special guy.”

And because Obama was not full of himself, Dettelbach adds, despite the fact that he “succeeded at everything he did, he was one of those people, even with all his success, where you still rooted for the guy.”

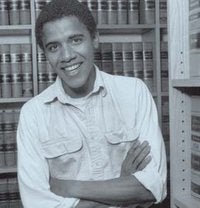

Barack Obama in 1990, the year he was elected president of the Harvard Law Review

HLS Professor Kenneth W. Mack ’91 saw Obama almost every day for the three years of law school because they were in the same 1L section and served together on the Law Review for two years. He remembers his first impression of the “tall, African-American guy” from Chicago “with an odd-sounding name.” Says Mack: “He seemed a bit older and a bit wiser than the rest of us. He was a very, very impressive and singular person, almost from the time you met him—very popular and well-respected in the section.”

When Obama was called on in class, Mack says, “He did very well. It’s a hackneyed expression, but true, that when Barack spoke, people listened. He had a quality that was different than other students; he always said something that was different and usually more considered. … A lot of people in class were very sharp and could argue about the doctrine and the case, but Barack always thought in broader terms, thought of the implications of what we were talking about in the larger world. That was one reason people really listened to him.”

Mack’s strongest impression of Obama involved a visiting professor who was deemed paternalistic by many in the class and who seemed to have little affection for the students. It was customary before the December break to present 1L professors with a holiday gift, but students were stymied on what to do in this case. “I don’t know who decided Barack should give the gift, but Barack did it, and did it in a very warm way,” Mack recalls. “He expressed such regard for this professor, regard in the respect we had for him as a professor, without downplaying the tension in the room. He turned what could have been a really awkward and somewhat negative moment into one that everyone could feel good about.”

Brad Berenson ’91, a partner at Sidley Austin in Washington, D.C., recalls Obama being elected as president of the Law Review because conservative students threw their support Obama’s way once it was clear a conservative candidate would not be elected. The conservatives saw Obama as more mature than other liberal candidates—a “safer, more trustworthy choice, a more natural leader. The conservatives also felt he was politically open-minded in a way others were not,” Berenson says. And, in Berenson’s opinion, they were right. “I thought he ran Law Review very well,” he says. “He led the group in putting out a quality volume that year, and he was relatively even-handed, politically speaking. He did not discriminate against political conservatives as some of the more liberal editors would have liked him to, so I and others among the conservatives appreciated that. He also formed personal relationships with a number of conservatives, which was something the far-left editors were more loath to do.”

Mack agrees with that characterization. “On Law Review we argued, very vociferously, on the personal and the political, and people didn’t like each other. [Obama] was one of the few people who was above all that. … Everybody understood he was a liberal,” Mack says, “but everyone thought they could talk to him, and he would listen, and there would be places he could find common ground with you.”

Berenson says he always liked Obama on a personal level and always respected his abilities: “I have nothing but nice things to say about him as a person.” As for what he sees in President Obama, he says, “I think the low-key, mediator style, the deliberativeness, the way he seems to run his White House staff—those all feel familiar.” However, he says, “the high level of partisanship is not familiar, is distinctly different. The themes he ran on in 2008, in which he portrayed himself as more of a post-partisan figure—that felt more familiar and felt truer to the person he seemed like during the Law Review years.”

Anthony Brown has a photograph of Obama and other students sitting in the common room of an off-campus residence hall, relaxing and talking, as they often did. Always welcoming and warm, Obama was never “a self-promoting person,” Brown recalls, adding, “He wasn’t the guy that had to be the smartest in the room—although he was.”

Jason Adkins ’91, a plaintiff’s attorney in Boston and one of the student leaders of the diversity protests, says participation by Obama—who had just been elected the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review—was key, especially when he spoke at the 1990 rally, at which HLS Professor Derrick Bell famously announced he was taking an unpaid leave of absence to protest the lack of diversity on the faculty. “It lent credibility to the effort because he was president of the Law Review, and it showed it was a cross-campus concern.”

David Deakin ’91, assistant district attorney and chief of the Suffolk County (Mass.) DA’s Family Protection and Sexual Assault Bureau, played pickup basketball with Obama during lunchtime. “He’s an outstanding basketball player, he’s very good, he’s very competitive about it,” says Deakin. “At the same time, he was always the one who would step in when tempers flared and remind people that this was a pickup game and not the NBA.” Still, says Deakin, “sometimes he would bump elbows.”

Mack also has a memory of Obama on the hoops court. “In the intramural league at the law school, there was an A league and a B league, and the Law Review’s team “was on the B league, of course,” says Mack, laughing. For the first game (and the first game only), Mack recalls Obama played on the Law Review team: “It was like Michael Jordan out there with a college team. You could see it kinda in his body language: ‘I don’t belong out here with these guys.’”

Adkins recalls running into Obama near Austin Hall around the time they were graduating. “I said, ‘What are you doing for the summer?’” Adkins says. “His response was, ‘I’m going to Mexico to write my autobiography.’ And I chuckled, and think I said something like, ‘You’re kidding me, right? You think you’ve got something to say at 30, 31?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I think I do,’ and off he went. And sure enough, he had plenty to say.”

Mitt Romney

Modest, unassuming, focused, analytical—for the most part, the Romney you see today is the same friendly but somewhat formal guy who, without fail, was prepared for class and has made great efforts to stay in contact with his friends over the past 40 years.

“There was a sense, even at that time, that this was a man you could trust.”

Mark Mazo

Mark Mazo ’74, a partner with the global law firm Hogan Lovells, met Romney within days of starting HLS in the fall of 1971, and they soon shared a study group of students who were “really smart and also serious,” Mazo says. But Romney had other desirable qualities: “He was a pleasant fellow, fun to be with. There was a sense, even at that time, that this was a man you could trust, who would work hard, and yet was fun and straightforward.”

Garret Rasmussen ’74, a partner with the law firm Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, sat next to Romney in many of their 1L classes. “He was very earnest and very excited and committed to law school, very much involved in the classes,” he says. “He had no objection to the Socratic method and always made an effort, always was prepared, was always eager to participate in class and answer questions, and was focused on doing well.”

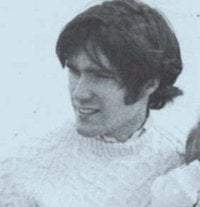

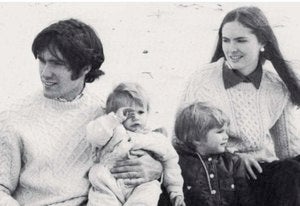

Mitt Romney with two of his sons and his wife, Ann, in 1973 while he was a student in the J.D./M.B.A program

Yet, while friendly, Romney—married, with young children, living in the suburbs—wasn’t part of the dominant counterculture at HLS at that time, classmates say. President Nixon was in office, and there was a great deal of anti-war sentiment on campus, Rasmussen notes. Many students voiced skepticism about lawyers selling out to the Establishment. Romney was not among them. In contrast to students in army fatigues and dirty clothes, Romney wasn’t rebelling, and “some days he wore a jacket; other days, a nice, ironed shirt,” recalls Rasmussen.

Romney has been described by some of his classmates as showing little interest in politics during that period. According to Rasmussen, Romney was always very focused on results: “learning as much as he could” and he “wasn’t going to be distracted by any of the political noise going on at the time. … It was almost as if he was in a different era, in a way, sort of like a Boy Scout. Those Boy Scout qualities, he has all of them—trustworthy, loyal, courteous, kind—everything you want.” Unlike so many at the time, “he wasn’t critical of anything, wasn’t complaining about anything. … At law school, he did everything politely,” Rasmussen says, so today’s “negative campaigning is surprising [and] out of character, but that may be beyond his control a little bit.”

In the fall of 1972, after his first year of law school, Romney matriculated at the business school as part of the joint-degree program, which included only a handful of students. HLS Professor Detlev F. Vagts ’51 headed the program and says he got to know the J.D./M.B.A. students better than most law students. Joint-degree students pass two different admissions processes, with the business school placing “a great deal more emphasis on background experience, personality and numerical competence,” Vagts says, while the law school focused primarily on academic record.

Vagts describes Romney as “pleasant, a little formal. People in the joint program tend to fall on one side or the other. … You could tell he was bottom-line business-oriented.”

Vagts had the most contact with Romney through a seminar he taught for joint-program students, in which Romney wrote a paper about the automobile industry. (Romney’s father had been president of American Motors Corp. and was chief spokesman for the auto manufacturing industry for years.) “It was quite a good paper,” Vagts recalls, which focused on a federal statute that had recently been passed by Congress to protect auto distributors from the then oligopoly of the American auto manufacturers. “He wrote about the statute and speculated about how it would be enforced because there was very little experience then [with the new law],” Vagts says. “He tried to figure out how a court would interpret the rules about firing [a distributor], having to be in good faith and so on. So it was a fairly technical, and I thought rather balanced, paper.” He chuckles, and adds, “He didn’t automatically come out for the manufacturers.”

At HLS, Romney graduated with honors although he did not serve on the Law Review. But at the business school he excelled, becoming a Baker Scholar, a prestigious academic honor reserved for the top 5 percent of students. The fact that he was one of the smartest students in class became apparent only gradually, says Janice Stewart M.B.A. ’74, since Romney—unlike some others—was “a bit modest about his gifts.”

Romney’s dedication stood out, even within a group of very serious students. “I can tell you there was never a time we got together when he was not prepared,” says Howard Serkin M.B.A. ’74, an investment banker in Jacksonville, Fla., who was in Romney’s core study group. Serkin also emphasizes that Romney “wouldn’t cut anyone else any slack. If he was going to be 100 percent prepared, he expected everyone else to be, too, and he was not bashful about saying that, in a polite but forceful way.”

Howard Brownstein J.D./M.B.A. ’75, president of a crisis management firm based in Conshohocken, Pa., was one of a small group of students in the joint-degree program with Romney. “The business school had a lot more influence on Mitt than the law school,” Brownstein says. And the HBS case method—in which students study real cases of businesses facing thorny problems they are required to try to solve—exerted enormous influence on all its students, says Brownstein. “The law school doesn’t teach law, per se; it teaches you how to think … so it’s all a little theoretical. Business school is very different,” he says.

He recognized the HBS emphasis on pragmatism in Romney’s tenure as a Republican governor in Massachusetts, where he had to compromise with his Democratic colleagues. “That’s exactly what the business school education would teach you,” Brownstein says. “The last thing it would teach you is to polarize and be extreme. That won’t get anything done. It’ll keep you pure but won’t get anything done. So it doesn’t surprise me that parts of the Republican Party have such a problem with him because he’s really not one of them. It wouldn’t surprise me, if he’s elected, that he immediately tells some in his party to pipe down, and reaches across the aisle to get things done.”

Mazo stresses his friend’s genuine decency. “A lot of people in law school and business school, you meet them, and you get the impression they’re kind of looking over their shoulder, [thinking], Who else here can help me in my future? Mitt absolutely was not like that.” Mazo worries that the warmth of Romney’s personality doesn’t come across via mass media: “He looks programmed, and that’s not him. He looks like he’s speaking from PowerPoints, which reflects an intellectual discipline, which he has, but that’s not him as a human being.”

Indeed, despite the intense demands of his professional life, Romney has made real efforts to join his former HBS study group at their five-year reunions. He once stopped in Boston for a dinner with the study group members at one of their favorite Boston restaurants on his journey from Utah to Athens, Greece, when he was heading up the U.S. Olympic Committee prior to the 2002 winter games. “A lot of people get to that level of prominence and blow their friends off, but Mitt Romney doesn’t,” Serkin says. “It was a huge effort to change his plans,” he says, “but it didn’t take much convincing.”

Romney never spoke of his privileged background nor bragged of his famous father, George Romney, the former governor of Michigan and secretary of Housing and Urban Development in Nixon’s Cabinet. “He was one of the guys,” says Ron Naples M.B.A. ’74, another member of the study group. “No one deferred to him, nor did he expect special treatment.” Romney once grabbed a jacket from his closet to walk Mazo and his then fiancée to their car after dinner at the Romneys’ home, and, noticing it had a Camp David logo, Mazo kidded Romney, who was clearly embarrassed, Mazo recalls. But when Rasmussen worked with Romney on a housing law project at HLS, he remembers that Romney didn’t hesitate to call his father to get some useful statistics. “That shows his level of commitment. He really wanted to do well,” Rasmussen says.

But Romney’s family and church were even more important to him than school, although he never pushed his religion on anyone, classmates say. Mazo, who is Jewish, remembers a long lunch conversation in the Harkness Commons in which he asked Romney probing questions about the Mormon church and got “good, serious, thoughtful responses.” At the end of the conversation, Mazo recalls, “he said in a most kindly way, ‘Mark, if you really want to know more about the religion, I’d be glad to talk to you about it.’ But he was not going to proselytize.”

Romney was “clearly devoted” to his wife, Ann, says Mazo, who recalls a dinner at the couple’s Belmont home where they discussed Romney’s two years of mandatory missionary work, which he spent in the working-class suburbs of Paris. Mazo asked Ann Romney if it was difficult being separated, and she told of getting special permission from the church to see Romney in Paris. Because romantic liaisons were forbidden during the missions, “she had to see him from afar, at an airport,” Mazo recalls. “She was looking at him from 100 yards away, and he was looking at her from 100 yards away. It was a wonderful feeling, she said—such an intimate feeling although they couldn’t touch, embrace, hold hands,” says Mazo. “I remember thinking that was one of the most romantic things I’d ever heard. The image I had was the Humphrey Bogart-Ingrid Bergman scene on the runway in ‘Casablanca.’”