The day after a deadly riot in the U.S. Capitol following a rally in which then-President Donald Trump and others repeated false claims that the 2020 election, which Congress was about to certify, had been stolen from him, Facebook took the stunning action of indefinitely suspending the president from its platform. Twitter, Trump’s favored means of communicating, went a step further and banned him for life, and other social media sites followed suit.

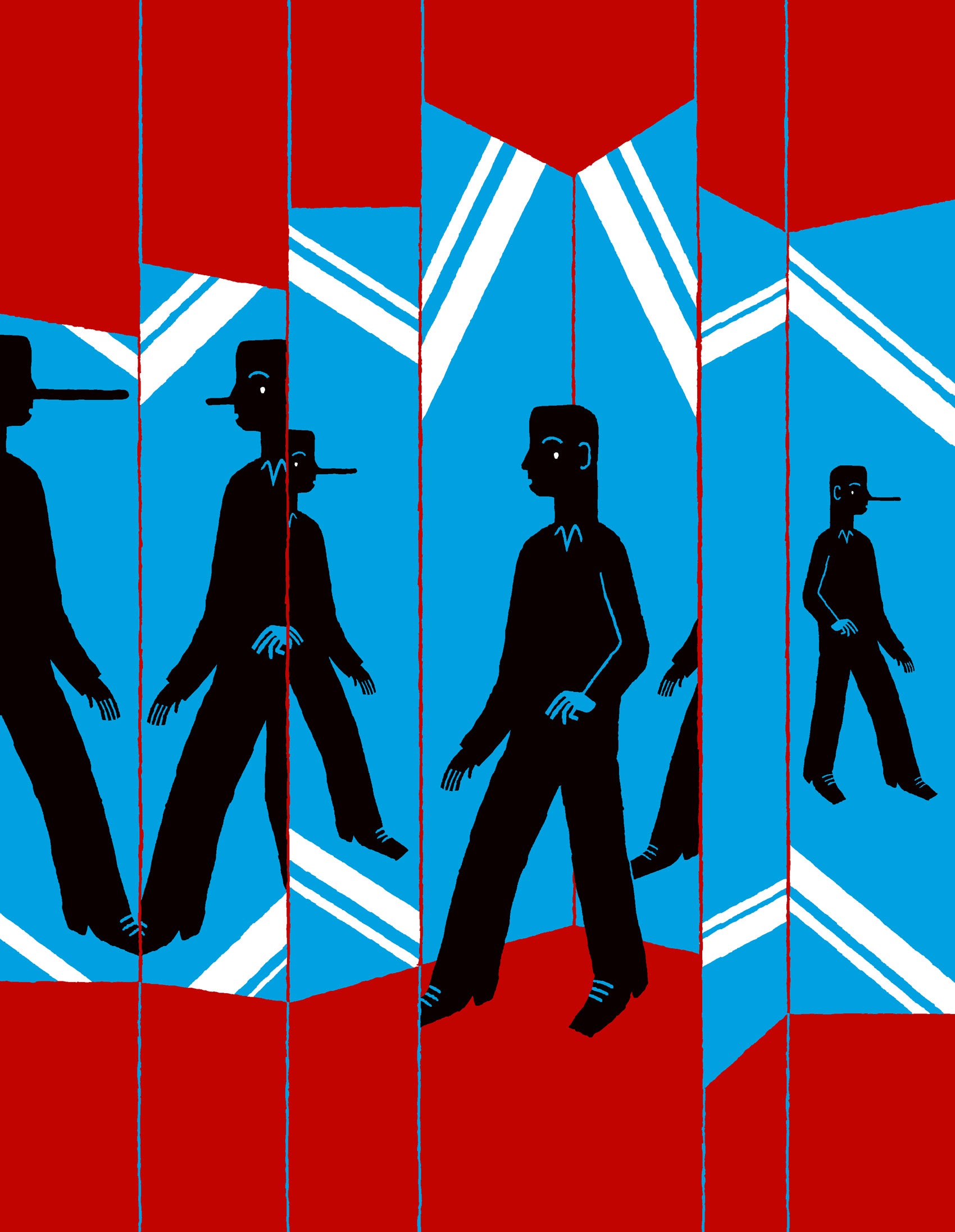

Suddenly, the leader of the free world was, if not silenced, certainly muffled — and by a handful of private companies whose immense power was undeniable.

Trump’s outraged supporters insisted his deplatforming proved that big tech is biased against conservatives. But even those who have been critical of President Trump, such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel, were troubled that these corporations had clearly demonstrated that, in some ways, they had more power than the president of the United States.

Still, the unprecedented actions seemed to achieve the desired effect. A week after Trump was barred from social media, The Washington Post, citing the online analytics firm Zignal Labs, reported a 73% decrease in online disinformation about the election. Many people believed that the social media giants were taking long-overdue action and assuming some responsibility for the serious injuries that disinformation begets.

In the months since Trump’s deplatforming, concerns about blatant and unchecked falsehoods on social media have only grown.

“It’s inexpensive — and in fact cheaper — to produce lies rather than truth, which creates conditions for a lot of false information in the marketplace,” says Harvard Law Professor Noah Feldman, an expert in constitutional law and free speech who serves as an adviser to Facebook. “We still collectively have a tendency to believe things we hear that we probably shouldn’t, especially when they seem to confirm prior beliefs we hold.”

Fake news is 70% more likely to be retweeted than the truth, according to a widely cited 2018 MIT study. If a healthy democracy relies on an informed populace — or at least one not deliberately disinformed by malicious actors — then the prevalence of disinformation is an existential threat. Social media is hurting people, society, even entire systems of government in ways unforeseen 20 years ago.

What, if anything, can or should be done? Whose responsibility is it to moderate social media content? Can social media be trusted to self-regulate? If not, should government be involved? How to strike a balance between free speech — a bedrock of American democracy — and other critical interests like safety, privacy, and human rights?

“This is a problem that is complex and pressing. There aren’t silver-bullet solutions,” says HLS Professor Jonathan Zittrain ’95, who is also on the faculty at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and at the Harvard Kennedy School. Author of the influential 2008 book “The Future of the Internet — And How to Stop It,” Zittrain is now working on a new book that he jokingly calls “Well, We Tried.”

“I feel we’re really at an inflection point where things are getting more heated,” says Evelyn Douek, an S.J.D. student and lecturer on law at HLS who co-hosts Lawfare’s “Arbiters of Truth,” a weekly podcast on disinformation and online speech. “The next few years,” she adds, “are going to be very interesting.”

Free speech vs. public health

Facebook has 2.8 billion users across the globe; Twitter, 192 million daily users. They and other social media outlets offer a reach and speed of communication that provide limitless possibilities for actors both good and bad. In March 2021, the Biden administration revealed that Russian state media and the Russian government were using Twitter to convince people that the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines could cause Bell’s palsy — a lie — in order to promote sales of the Russian Sputnik V vaccine. That same month, Russia announced it was slowing down the uploading of photos and videos to Twitter because the company refused to remove content banned by the Russian government. In other countries, such as Myanmar, social media companies are accused of allowing their platforms to spread state propaganda that has led to serious human rights abuses.

Social media companies, in part from a sense of self-preservation, are showing a new willingness to self-regulate. Twitter has kicked off 70,000 QAnon conspiracists since January, and in March, Facebook banned Myanmar’s military leaders after years of public criticism for its failure to do so. At Feldman’s suggestion, Facebook created an Oversight Board, designed to be an independent body that reviews its content moderation decisions, including the one to deplatform Trump. At the same time, there is a flurry of proposed laws to regulate social media, a type of governmental interference unimaginable in the early days of the internet.

This rapidly changing landscape shows how drastically public opinion has shifted from a strongly pro-free speech stance.

“I think there’s been this turn away from ‘just let the tweets flow’ into thinking more about what harms are caused by this ecosystem and what guardrails we need on free speech to make [the internet] a healthier and more positive space,” says Douek.

Zittrain divides digital governance into three eras, starting with the “rights era” from 1994 to about 2010, when free speech reigned and the protections of the First Amendment prevailed. “There was this idea of the internet as a really open space,” he says, “a free-expression paradise. It just couldn’t be regulated and that was inherently democratizing.”

Around 2010, growing concerns about the sometimes deadly consequences of unfettered online speech led to what Zittrain calls the “public health era.” It was a name he meant as a metaphor, but in 2020, it became very clearly literal when disinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic, including bizarre “cures,” led to actual deaths. A more absolutist view of the First Amendment began to give way as more voices asked whether private social media platforms had a social responsibility to interrupt the broadcast of (and profit from) unhinged conspiracy theories that could hurt or even kill people.

Today, the metaphor of the marketplace of ideas, where truth eventually emerges as the winner, no longer works, says Mark Haidar J.D./M.P.P. ’23, who is studying the impact of disinformation on voting rights and U.S. democracy in an HLS/Harvard Kennedy School program. “We have an ‘information disorder’ where we’re flooded with information and it’s hard for people to sort between high- and low-quality information or false information,” he says.

As a result, the “hands-off-my-free-speech” model no longer satisfies many people. Social media companies are “under enormous public pressure because they have power to amplify messages that can turn the course of an election or affect the path of a communicable disease, and everyone is aware of the power they have,” says Zittrain. “And the choice not to intervene is as much an exercise of power as the choice to intervene.”

Today there are signs that we are entering what he calls the “legitimacy era,” with more acknowledgment of the need to balance free speech and other interests like safety, and attempts to create processes to do so. Facebook’s Oversight Board is an example. “I think we’ll be seeing more and more of that,” Zittrain says.

But if we turn away from the “just-let-the-tweets-flow” model, as Douek calls it, where do we go?

Searching for solutions

This question is at the heart of the work of the Assembly: Disinformation program at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard. Established by Zittrain, the program is convening a broad range of thought leaders from academia, industry, government, and civil society to explore the problem of disinformation in the digital public sphere and try to forge solutions. In the past, the Assembly program examined cybersecurity and artificial intelligence, but for the past two years it has been focusing on the factors that incentivize people to spread disinformation, and who — if anyone — should be responsible for regulating the online ecosystem.

One of its current projects is Disinfodex, a publicly available and searchable database of disinformation campaigns by social media platforms created by a group of cross-disciplinary experts who serve as Assembly fellows. Within a cohort of student fellows, a group is examining the for-profit model of social media platforms, where companies push content — and make more money — by leveraging a user’s personal data to develop sophisticated algorithms that keep them online and scrolling. How? Often, by presenting them with increasingly extreme content, some of which is not only false but potentially dangerous.

Assembly student fellow Isabella Berkley ’23 is working with her team on a project that’s looking at promoting a values-driven approach among social media companies. “What if the onus of preventing passive scrolling wasn’t on users but on the creators, where you might have a situation where the disincentive to limit disinformation is higher because it would go against the creative values of these companies?” suggests Berkley, who worked at Facebook as a child safety investigator. She is also interested in finding ways to encourage people, particularly minors, to view themselves as in control over their use of social media rather than feeling powerless to decline whatever is pushed on them.

Haidar, a student fellow on a different team, wants state governments to encourage digital literacy, and nonprofits such as AARP and similar groups to mount tailored campaigns to combat disinformation. Feldman says educators and media have a role in drawing public attention to the prevalence of false information but notes that alone isn’t enough.

It was in 2018 that Feldman first proposed to Facebook the idea of an independent body to review the company’s content decisions. So far, the board, which is purely advisory, includes 19 lawyers, human rights experts, and others from around the world, and has heard seven cases — most recently issuing its assessment of the deplatforming of former President Trump. On May 5, it upheld the ban, at least temporarily, but said that an indefinite suspension wasn’t appropriate and gave Facebook six months to decide Trump’s status. Although the decision has been met with criticism from those on both the left and the right, Feldman says, given the challenges of this case — which is likely to be the biggest it ever decides on — he believes the board did remarkably well. “They correctly told Facebook, if it’s going to infringe on free expressions values, it has to do it through clearly stated rules, not in an ad hoc way.” In early June, the company announced that Trump’s suspension would last at least two years.

Outside of the U.S., many countries are considering strict restrictions on social media. These efforts are more likely to succeed in countries where free speech doesn’t enjoy the protections of the First Amendment, Douek and others note. But even in the United States, many are pushing for legislative change. There are currently dozens of proposals to reform or repeal Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects social media companies from liability for user-generated content. John Palfrey ’01, former HLS professor and executive director of the Berkman Klein Center, who now heads the MacArthur Foundation, is among those who believe it is time to amend Section 230, as he said in this year’s HLS Klinsky Lecture. The protection it provides companies has led to growth, competition, and innovation, he said, but it’s also “led to many bad acts and to many companies turning the other way when law enforcement or aggrieved parties come calling.”

How proposals for reform will fare against the First Amendment is as yet unknown, and, in general, conservatives and liberals have different views of the problem, let alone of the best solutions.

“Clearly there’s a lot of appetite for statutory reform, but people don’t really know what they want, and they have conflicting goals for potential reforms,” says HLS Professor Rebecca Tushnet, an expert in copyright law who writes the false-advertising-focused legal blog 43(B)log. “There’s a group that wants the internet companies to take down more content and a group that wants them to take down less content,” particularly regarding divisive issues such as the 2020 election and COVID-19 vaccines. Still, there is bipartisan support in the Senate for the Honest Ads Act, which would require more transparency in digital political ads, similar to that required for those on TV and other traditional media.

To Tushnet, the real problem with social media companies is that they are monopolies. “If we had a revitalized anti-monopoly approach throughout the economy and not just in big tech, we might make some progress on the issues dividing us,” suggests Tushnet, who would start by breaking up Facebook. “Just to be clear, that wouldn’t get rid of a lot of awful speech, but it would change the ways awful speech got distributed.” There are pending antitrust suits against both Facebook and Google, she notes, although “whether those suits will go anywhere is a good question.”

Social media isn’t the biggest problem

While there’s a role for social media outlets to make changes, focusing on them is missing the real culprits, argues HLS Professor Yochai Benkler ’94, faculty co-director of Berkman Klein, and “no amount of intervention and regulation of social media will make a meaningful dent on misinformation in America.”

Social media plays a secondary role to the real purveyors of disinformation, he says, those whom he calls “elite actors,” including both politicians like Trump and others in the GOP leadership and media elites, primarily Fox News and talk radio, which Benkler argues have spread untruths to their advantage. Beginning in the 1980s, he says, white identity and evangelical audiences had formed a distinct market segment, and Rush Limbaugh and later Fox found that “it’s a really lucrative business model to supply identity-confirming, outrage-stoking narratives that reinforce their identities and systems irrespective of their truth.”

It’s a conclusion Benkler reached after analyzing massive amounts of data during both the 2016 and 2020 election cycles, resulting in an October 2020 paper he co-wrote with others at Berkman Klein, “Mail-In Voter Fraud: Anatomy of a Disinformation Campaign,” which analyzed over 55,000 online media stories, 5 million tweets, and 75,000 posts on public Facebook pages.

“The pattern is very, very clear,” says Benkler. “It’s a combination of active disinformation on the right and a large component of the mainstream press not being sufficiently well trained to deal with an asymmetric propaganda system.” Some 20% to 30% of the population, who are “mostly politically inattentive because they are busy with other things,” get their news from local and network TV, and/or regional and local newspapers, not social media.

“I’ve been saying this since the book I wrote in 2018 —the people with the most power to do something useful are mainstream reporters and editors and mainstream media,” says Benkler, referencing his book “Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics.”

Only since last August and September, he says, have traditional media such as the major newspapers and networks been willing to explicitly call out untruths and lies. “The traditional media outlets need to practice a much more aggressive policing of propaganda and disinformation,” he urges, “which is not being anti-Republican or politically biased; it’s about being explicitly focused on evidence and objective truth to the extent it is achievable, and being explicit when one or other party lies or gets it really wrong, and putting that right up front.”

There is one thing on which all seem to agree: The situation is becoming more urgent by the day.

“Nothing will solve everything,” says Douek. “We have so many problems, and we’ll need lots and lots of different solutions.”