Fields of Dreams, Fruitful Lands

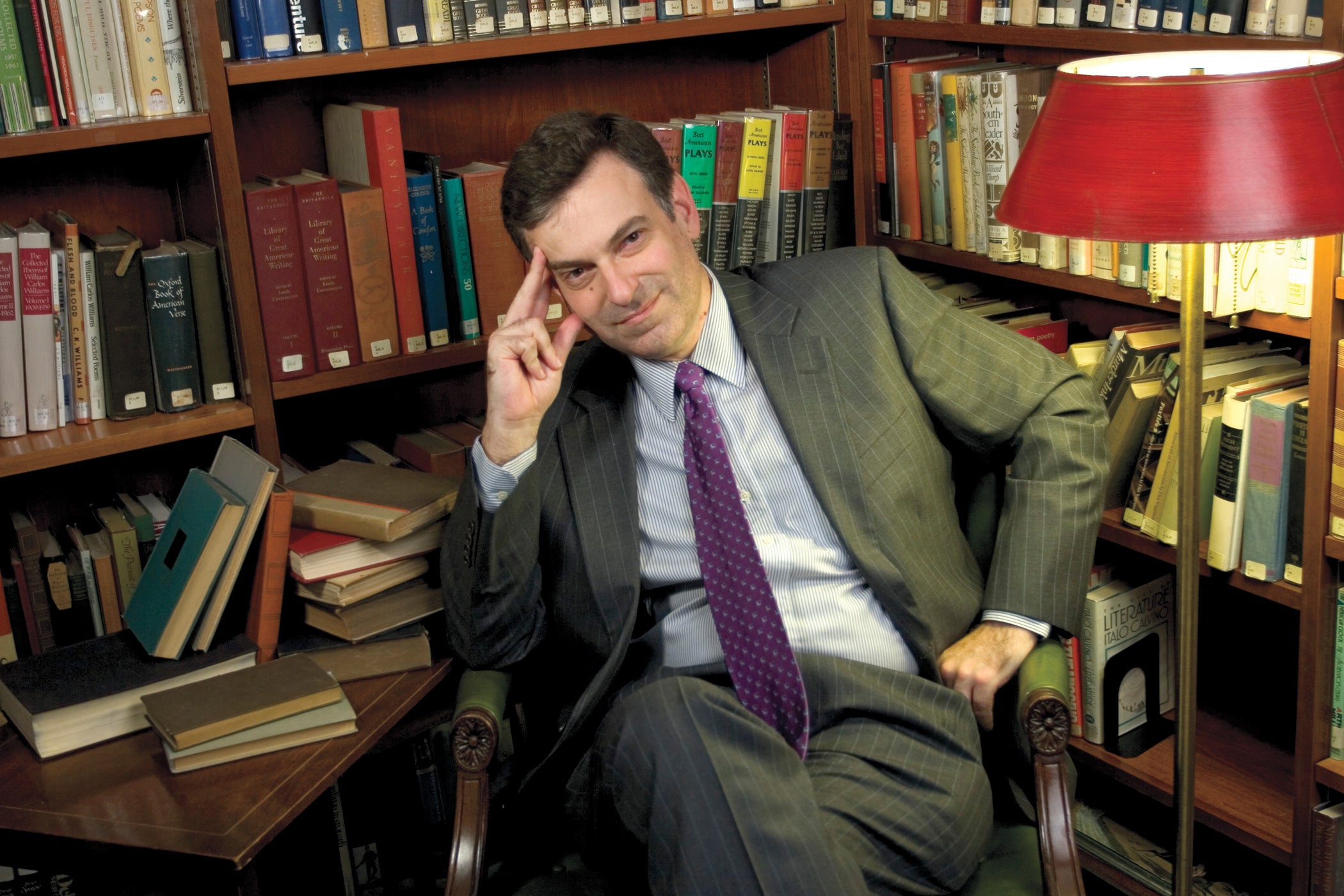

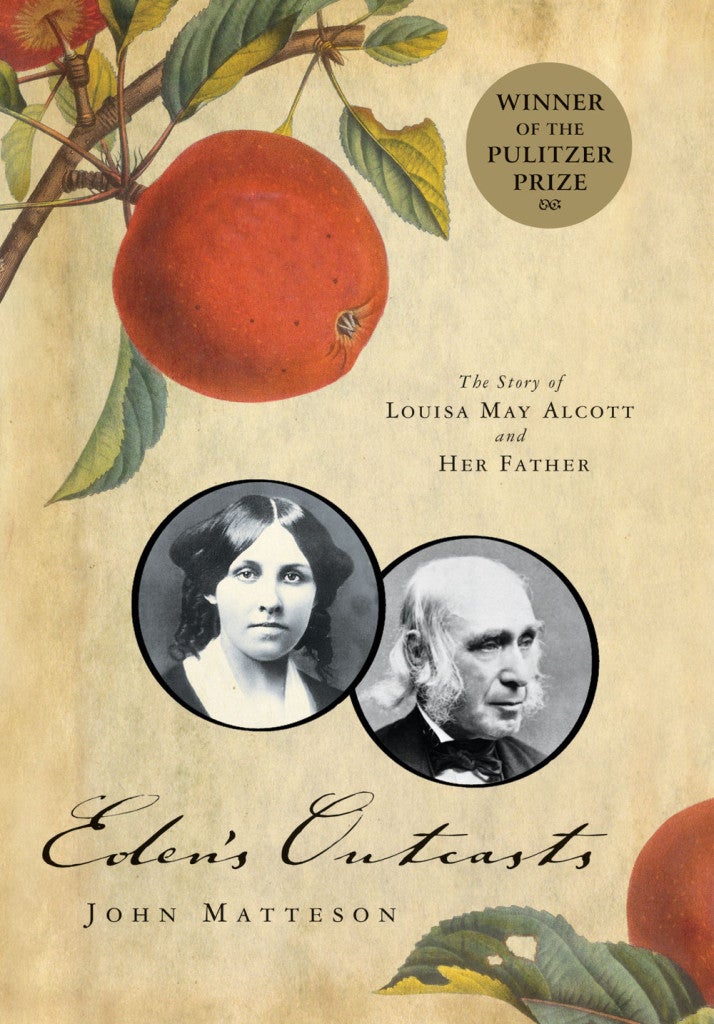

Louisa May Alcott once described a philosopher as “a man up in a balloon” tethered to the earth by his family. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, “Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father” (Norton, 2007), John Matteson ’86 chronicles the tension and affection in that vertical relationship.

Her father, Bronson Alcott, was a self-educated transcendentalist whose high-minded efforts too often ended in disaster. When he founded the innovative Temple School in 1834, it won him praise from Boston intelligentsia. But by 1837, a book he’d written about his classroom elicited such outrage and derision that he lost the school and his reputation.

In 1843, he brought his family (including 10-year-old Louisa) to live off the land with a miscellany of reform-minded individuals. Fruitlands, their social experiment, ended seven months later, in hunger, cold and the near dissolution of the Alcott marriage and Bronson’s mental health.

As Matteson tells it, the four Alcott girls experienced dazzling intellectual riches combined with material deprivation. Thoreau took them boating on Walden Pond and gave them “an easy, practical course on how to love the world.” Emerson opened up his library. Yet food was sometimes scarce and prospects for the next year’s housing uncertain. In a moment of impatience, Bronson’s saintly wife summed him up: “No one will employ him in his way; he cannot work in theirs. … I believe he will starve and freeze before he will sacrifice principle to comfort. In this, I and my children are necessarily implicated.” For Louisa, that translated into an obsession with supporting the family, which abated only after “Little Women” made her one of America’s most successful female writers.

Matteson, a former litigator, now a professor of English at John Jay College, paints a vivid picture of the period, from the years before the Civil War, when the Alcotts hid runaway slaves and received the wife of the executed abolitionist John Brown, to Louisa’s war service—in a makeshift hospital in the capital. After the slaughter at Fredericksburg, she tended to wounded and feverish soldiers, eventually succumbing to typhoid herself. (She recovered from the disease, but never from the mercury-based treatment.) Her first big literary success, “Hospital Sketches,” came from what she saw in the ward. Her service also shifted her relationship with her father. He later wrote to his wife, “Our children are our best works.”

Despite Bronson’s detachment from material concerns, Matteson says he was an exceptionally present parent who “devoted more of himself to his children than almost any other man of his generation.” He chronicled their development, keeping detailed journals from the time they were born. Someday Matteson hopes to publish these “foundational works of child psychology and transcendentalism,” which also offer a rare look at the infancy of a famous writer.

Matteson says there are moments of incandescence in Bronson’s own writing—but they are the exceptions. Where Bronson was at his most eloquent, it seems, was in the ephemeral act of conversation. He traveled the country on speaking tours into his 80s, elevating conversation to a performance that Matteson likens to jazz.

On sabbatical this year, Matteson is happily at work on a biography of another transcendentalist, feminist Margaret Fuller, but the Alcotts hold a special place in his heart, in part because of their conflict—and closeness. On his deathbed, Bronson said to Louisa, “I am going up. Come with me.” And after the man in the balloon left this earth for good, she did—three days later.

Matteson himself has a daughter (now 14), and when he started the project, he felt he could apply what he knew about that relationship and perhaps learn something about being a better parent. The book’s success, he believes, is related to the fact that it was such a personal journey.

Matteson says the Pulitzer has also been a validation of his decision nearly 20 years ago to leave the practice of law in pursuit of a much less certain career in the humanities. What helped him to take the plunge was not a text by one of the transcendentalists (whose work he’d come to love in a Harvard College seminar he took during law school). It was a movie about a man with seemingly unrealistic aspirations. “People think ‘Field of Dreams’ is about baseball,” he says, laughing. “But it’s really about a character who follows his own moral compass.”