Not many people attend an event in Cambridge and end up in Tanzania. But that is precisely what happened to Gerald Gillerman ’52, a Massachusetts Appeals Court judge.

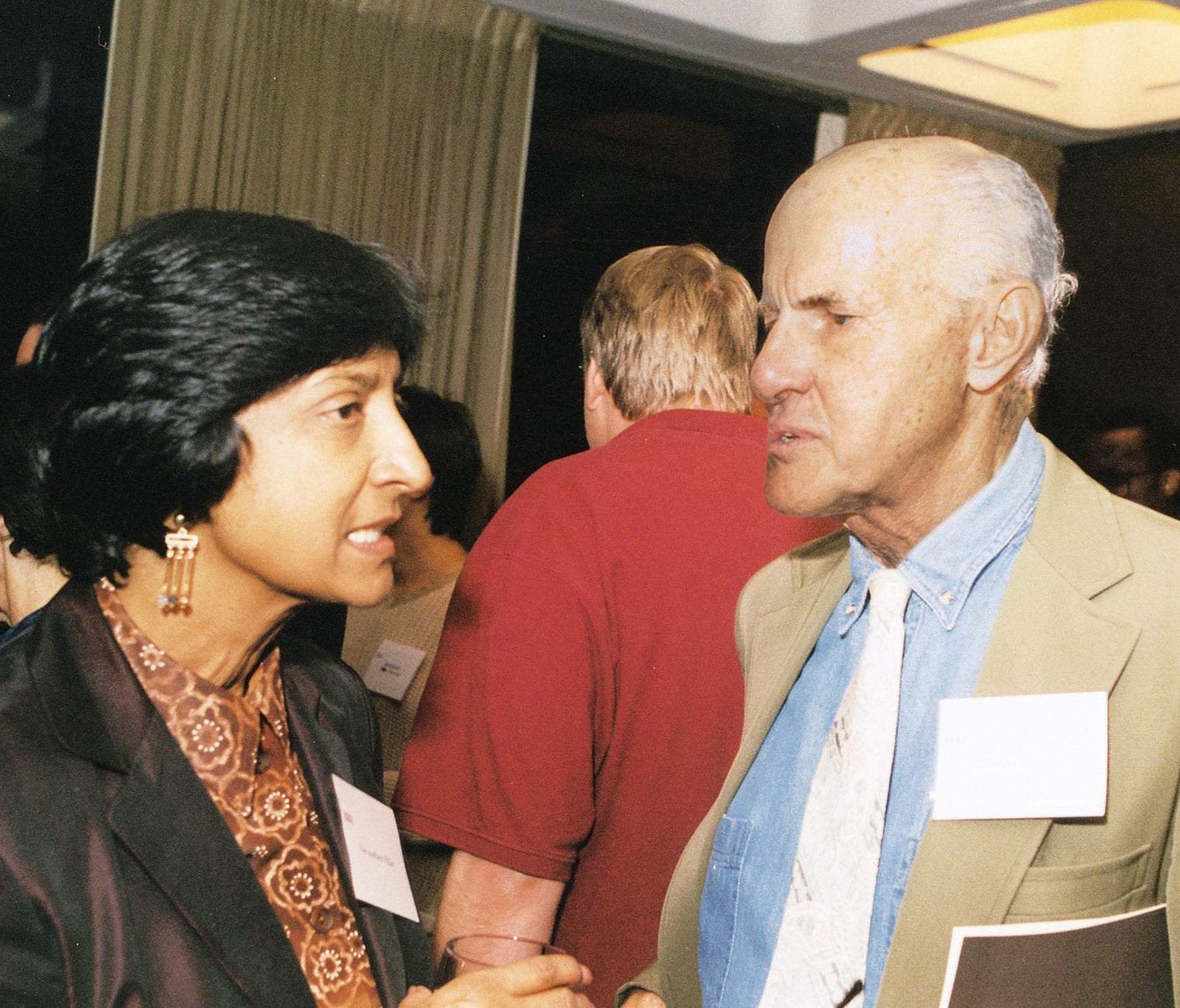

Gillerman had met Navanethem Pillay LL.M. ’82 S.J.D. ’88, the recently elected president of the International War Crimes Tribunal of Rwanda, at the 15th anniversary of the HLS Human Rights Program, held last year at the School. “I introduced myself, and we talked for a bit about problems at the Tribunal.” Gillerman asked whether he could help.

The two corresponded, and as a result Gillerman was invited to the Tribunal’s court facilities in Arusha, Africa, as Judge Pillay’s “special guest.” Gillerman recalls the week he spent there as “the most exhilarating professional week of my life.”

“There are a lot of problems confronting the ad hoc Tribunal for Rwanda—language, culture, criminal procedure, and substantive law,” he said. “But I wasn’t representing anybody else, I had no conflicts, and we had many productive conversations.”

Peter Rosenblum, associate director of the Human Rights Program at HLS, praised Gillerman’s participation. “Judge Gillerman carefully examined the issues the Tribunal was facing. By his scrutiny, he made a genuine contribution at what was really a very delicate moment.”

During Gillerman’s time in Tanzania, the Tribunal considered the case of Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, who was charged with genocide and crimes against humanity, stemming from the 1994 fighting between Tutsi and Hutus that claimed an estimated 800,000 lives in Rwanda. The Tribunal released Barayagwiza with prejudice because his rights as a defendant had been compromised by allegedly excessive delays in announcing the charges against him and in his arraignment.

“Barayagwiza could walk away, never to be tried or charged again,” said Gillerman. “They stood human rights on its head.” The government of Rwanda threatened to separate itself from the Tribunal over the ruling. On reconsideration, however, the Tribunal reversed itself and ordered Barayagwiza to stand trial.

“In the United States, our greatest concern is that an innocent man may be convicted, so we have a careful system of rules to minimize that possibility,” Gillerman said. “The risk facing the Rwanda Tribunal in the trial of major figures is just the opposite, that the guilty may go free. And the question becomes, how do you minimize the risk of error in both directions?”

Gillerman feels “hopeful” after the Arusha experience. “Let’s face it, there are a lot of problems to be solved. But in the long run, an international system of criminal law must be achieved.” ❚

—Flynn Monks