Four HLS professors consider whether the old rules apply when the enemies don’t wear uniforms and are willing to die with their victims

As long as humans have engaged in warfare–about 4,000 years–we have been making up rules to govern it. We’ve sought to identify the causes that must be present for a “just” war. We’ve set up ground rules to regulate which weapons, which military practices, exceed the bounds of acceptable use and aspired to specify the treatment that combatants should receive when taken prisoner.

But after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and the subsequent declaration by President Bush that the United States was waging a “war on terror,” the rules have been thrown into question. Some leaders immediately branded the attacks a call to war equivalent to the Japanese assault at Pearl Harbor in 1941. But while the impulse to counterattack may have been similar to that which prompted the U.S. entry into World War II, the two events were vastly different in other ways. The international laws of war are quite clear about identifying the grounds for military retaliation when one nation is attacked by another. But on Sept. 11, 2001, the United States was attacked by a stateless organization. And the international laws of war, developed to govern the actions of states with identifiable flags and uniforms and geographical borders, have little to say about how to conduct a war against large, transnational terrorist organizations that are not military branches of particular states.

Does existing international law create impediments for the United States in seeking to prosecute wars against nonstate groups? Legally, how are we faring in this effort? Does international law need to be changed to address the new terrorist threat?

At Harvard Law School, faculty members who teach international law and who have written about terrorism have given thought to questions like these. And while they all believe that change is needed in developing responses to terrorism, they differ when it comes to what the right course should be.

In addressing the limitations of international law in dealing with groups like Al Qaeda, Assistant Professor Ryan Goodman pointed out that international law is not silent on the subject of war between states and nonstate actors. “The fact that Al Qaeda is a transnational terrorist organization does not pose exceptionally new questions for international law and policy,” he said. “There is ample experience in dealing with organizations whose modus operandi involves behavior that is nonreciprocal and directly opposed to basic principles of humanity.” He points out that the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, passed in 1977, applies to nonstate national liberation groups, and the statute that created the independent International Criminal Court in 1998 “expressly applies the laws of war even to conflicts between two nonstate actors.” In addition, he says, Article 3 of the four Geneva Conventions, which addresses wars between a state and nonstate actors in the context of a civil war, is relevant.

However, Goodman said, an organization like Al Qaeda is impervious to international law: “That Al Qaeda has the unique potential and desire to use weapons of mass destruction, that their objectives are not ones we would subject to negotiation or compromise and that their suicidal methods render many of their members undeterrable, pose exceptionally difficult questions for some areas of law and policy.”

“The problem is that the laws of war assume that the enemy also complies with the laws of war,” said Professor Jack Landman Goldsmith, who joined the Harvard Law School faculty this fall after serving as head of the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel last year. “And they often create penalties, such as a loss of protections, if a party to the conflict doesn’t comply with the laws of war. They also assume that the enemy is going to distinguish itself from civilians and that it does not attack civilians.”

Goldsmith contends that the actions of Al Qaeda, in particular, have obliterated those assumptions because it has structured itself not only to violate the laws of war, but to take advantage of violating them. “So the challenge is to figure out what rules apply to an organization that, by its very nature, flaunts the laws of war and undermines their key assumptions,” he said. “And that’s a really, really hard challenge.”

The existing laws of war are mostly products of 19th- and 20th-century conflicts and are largely contained within the four Geneva Conventions adopted in 1949 to address warfare against civilian populations and noncombatants, a particularly horrifying characteristic of World War II. There were also other treaties, such as the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the Geneva Protocols of 1977, which include the regulation of the means and methods of warfare, and others that prohibit practices such as torture and the use of chemical weapons.

However, as Goldsmith observed: “It’s certainly the case that the laws of war were not fully developed to answer all the questions about a war between a state on one hand and a nonstate actor/terrorist organization on the other. In some sense, they need to be updated to address this situation. How that should happen is a hard question to answer.”

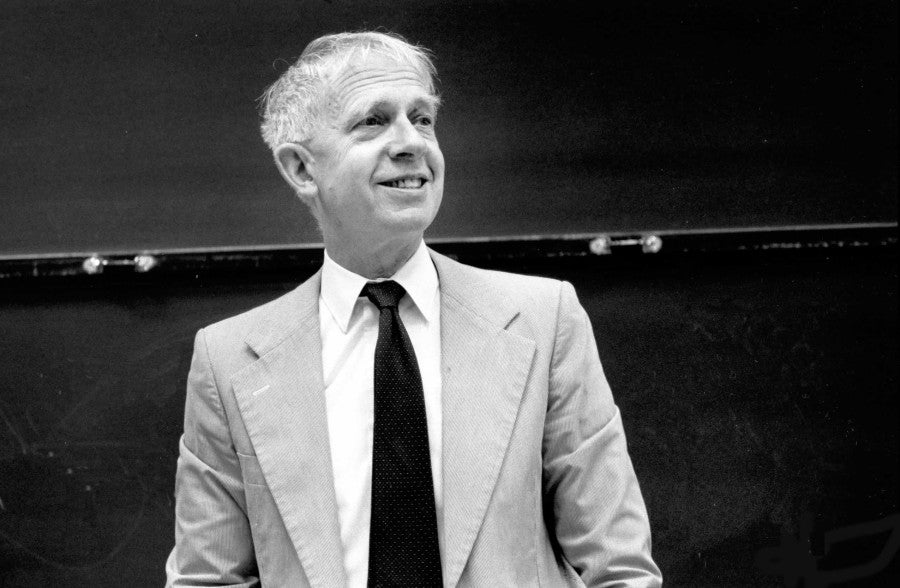

To Professor Alan M. Dershowitz, author of the book “Why Terrorism Works: Understanding the Threat, Responding to the Challenge” (Yale University Press, 2002), one of the shortcomings of the international laws of war in dealing with nonstate terrorists is that they don’t address how to deal with combatants who are also civilians. “Terrorists are taking advantage of anachronistic international law,” he said. “International law makes a sharp distinction between military and civilian–those in uniform and those not in uniform. But I’ve written about what I call a ‘continuum of civilianality,’ which recognizes that civilianality is a matter of degree, that there’s an enormous difference between a child going to school and a religious leader of Hamas who gives instructions to turn on and off the terrorist button. The guy from Hamas is much closer to a combatant than the schoolchild, and we have to recognize that.”

Dershowitz believes that the first step in mounting a sensible international response to terrorism is to change international law. But exactly how nations might go about doing that is not clear. “There has to be a forum for applying international law fairly,” he said. “There’s no international legislature that has any real authority, and you can’t even get the U.N. to condemn terrorism. They hem and haw and talk about it as international liberation movements and that sort of thing.”

Nevertheless, Dershowitz believes that the International Court of Justice, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations, might play a role in changing the U.N.’s approach. And the International Criminal Court, which came into force in 2002 as a permanent, independent body to try individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, “also holds some hope for the fair application of international law.”

Even if there is no effective international decision-making venue, Goldsmith says, there are ways in which nations can develop rules on dealing with terrorism. One way to do that, he suggests, is through treaties. “States can get together and decide how terrorists should be treated,” he said. However, he believes that treaties might be difficult to achieve. “It’s always been hard to regulate terrorism because people have such different conceptions of what terrorism is–when it’s legitimate and when it isn’t.” Another route, he said, is through customary law, when states facing a new threat “work out through diplomatic channels, through experiment and through back-and-forth arguments what the appropriate rules are.”

Dershowitz agrees with the idea that nations can act in a somewhat autonomous fashion to form new rules that can become accepted as international law. As a case in point, he refers to Israel’s air strike against an Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981. That strike, timed to occur on a Sunday when the chances of collateral damage would be at their lowest, resulted in one casualty. The attack was immediately condemned by the U.N. Security Council. “However, Israel’s actions today are widely recognized among international-law scholars as having been just and correct,” he said. “So even though the law condemned them, the action became self-proving. The world essentially thanked Israel for depriving Saddam Hussein of nuclear weapons. When you read international-law accounts today, almost everybody says that what Israel did in 1981 was acceptable in international law notwithstanding the fact that it was condemned.”

Still, unilateral action on the international stage can be risky. Professor Detlev Vagts ’51 points to the U.S. creation of “military commissions” and the attendant uncertainties surrounding legal rights of detainees as having a strong bearing on how effectively extradition will work in bringing terrorists in other countries to U.S. justice. “Other countries may have inhibitions because they don’t think that trials by military tribunals are a good idea,” he said. “They may be inhibited from turning people over to us if we impose the death penalty.” Furthermore, he said, the revelations of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib might also discourage extradition: “I think people are beginning to be afraid that [cases] might be mishandled.”

But when it comes to the rights of prisoners, Dershowitz suggests that the traditional calculus needs to be changed when the equation involves terrorism. He writes in “Why Terrorism Works” that, while normally it is better to let 10 murderers go free than to convict one wrongly accused defendant, the same principle doesn’t apply when it comes to terrorists with access to weapons of mass destruction. He suggests that in some instances torture might be warranted in combating terrorism. He calls it the “ticking-bomb scenario,” in which there is good reason to believe that a detained terrorist knows about a ticking nuclear bomb. Dershowitz argues that torture may be the right action to take in that instance, and he further argues that a system in which judges would issue warrants, just as they do search warrants, would provide the proper accountability.

Not all scholars think that torture warrants are a good idea. “Problem number one is that the Convention Against Torture explicitly says, No excuses,” Vagts said. “So we would be violating that. Maybe America could do it in a correct and humane way with conscientious judges, but there are a lot of countries that are signatory to the torture convention that don’t have those institutions. The second problem is: I’ve never seen that case. For one thing, I don’t think you’d have time to go to court.”

Detention and torture have already arisen, of course, as controversial issues in the U.S. war on terror. What does international law have to say about them? The revelations of torture at Abu Ghraib have been broadly, if not universally, condemned as apparent violations of international law. And there have been other reported infractions. “You can’t withhold the names of POWs from the ICRC [International Committee of the Red Cross],” Vagts said. “The ICRC is entitled to know who they are so they can inform the next of kin and keep a registry and get to talk to the prisoners. We violated that. And then, of course, there was the unpleasant case of an Iraqi general who turned up dead in our custody.”

“We seem to have gone into Iraq in confusion,” Vagts said. “For example, we declared that Saddam was a POW, but before we did that, we published these photographs of him being worked over by a doctor. You’re not supposed to publish photos; that’s against the Geneva rules for a POW. They wanted to make sure that the Iraqis knew that this guy was helpless and couldn’t defend himself. But if he was a POW, that was against the rules.”

While some prisoners at Abu Ghraib are clearly covered as POWs by the Geneva Conventions because they have been detained as participants in what is, at least nominally, a traditional interstate war, those being held at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, are a mixed set. One prisoner group there comprises people who are suspected Al Qaeda members, and the other is made up of suspected members of the Taliban from Afghanistan.

“The president determined that the Geneva POW Convention did not apply to Al Qaeda because it is a nonstate actor,” Goldsmith said. “As for the Taliban, though, Afghanistan is a state party to the treaty. So the POW Convention does apply to the conflict with Afghanistan armed forces–the Taliban. But the POW Convention assumes that, to get its protection, the enemy must satisfy certain criteria. The U.S. government determined that the Taliban were unlawful combatants because they didn’t distinguish themselves from civilians, they didn’t carry their arms openly and they didn’t comply with the laws of war. And–this is a fine but important distinction–even though the POW Convention did apply in the war between Afghanistan and the U.S., the Taliban forfeited its protections.”

The term “unlawful combatants” used to describe the Taliban group at Guantanamo has drawn attention as a questionable designation that some observers suspect provides the United States with an excuse to skirt international law in its treatment of Taliban detainees. Goodman, however, says that term is, in fact, well-established as a relatively old category in the laws of war. “[It] can be conceptualized as an individual or civilian who unlawfully takes up arms,” he said. “The question is what implications result from that status besides the loss of POW status. The ICRC and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia maintain that all individuals are either covered by the POW Convention or the Civilians Convention [of the Geneva Conventions]–that there is no gap. While there are potential problems with that broad reading, unlawful combatants are covered by Article 3 in all four Geneva Conventions. In addition, the Civilians Convention contemplates unlawful combatants, as evidenced by its security proviso allowing states to suspend some rights protections for such individuals.”

Dershowitz criticized the approach taken at Guantanamo as “too wholesale” in its intake of combatants: “International law requires a relatively fast decision about the status of people–whether they’re military combatants, prisoners of war, criminals, spies. We didn’t do that.”

The U.S. Supreme Court has stepped in to say that prisoners can challenge their detentions in U.S. civilian courts. But as Vagts points out, the High Court only talked about screening procedures; it didn’t address the issue of what can be done with terrorists after that. “Of course, terrorists and unlawful combatants are sort of outside the rules on warfare,” Vagts said. “They don’t get to be prisoners of war. All they get is a sort of bare level of treatment.” Furthermore, he said, “it is not clear under any of these rules how long you can hold people if you don’t charge them with a crime.” He believes that an international convention should be organized to sort out the problem.

In the meantime, Vagts and his colleagues agree, now that the United States has declared war on a stateless threat of terror, new answers on how to conduct the campaign must be developed.

“We have to come up with a set of rules that is appropriate to apply to organizations that are difficult to identify and that flagrantly violate the laws of war,” Goldsmith said. “We have to come up with ways that authorize states to respond adequately to the terrorist threat while at the same time come up with appropriate limits on the powers to respond.”