Crucial classroom conversations

“Law school is still, and I hope will continue to be, less a trade school and more an intellectual journey that aims to prepare students for doing law in a way worthy of a society we want to live in. The harder it may be to have reasoned dialogues about matters of importance in our society, the more crucial it is for professors to practice doing so with their students.”

—Professor Jeannie Suk Gersen ’02, from “The Socratic Method in the Age of Trauma”

Student activism in perspective

“Like the struggles at Harvard in the 1980s, today’s student activism must be read as a chapter in the ongoing conflict between the liberal center and the critical left on how to conceptualize the contemporary implications of American Apartheid. From yesterday’s contestations over the ideals of colorblind meritocracy to today’s interment of the short and bittersweet romance with post-racialism, race liberals and their radical critics have struggled over the terms of engagement with legal institutions and their role in reproducing racial hierarchy.”

—Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw ’84, professor at UCLA School of Law and Columbia Law School, from “Race Liberalism and the Deradicalization of Racial Reform”

The law and justice gap

“Justice is both deeply contested and central to the study of law and legal institutions. The question of what is just is, of course, not congruent with the positive question of what is law. … But the gap between law and justice is not one to be relished: Law ought to aspire to reflect deeply held community conceptions of justice.”

—Professor Vicki C. Jackson, from “Thayer, Holmes, Brandeis: Conceptions of Judicial Review, Factfinding, and Proportionality”

When law is not really law at all

“It is not surprising … that most of the important debates in jurisprudence over the past 200 years have been about the boundaries of law, and about the extent to which what some have thought of as non-law is, or has become, law, and occasionally about the extent to which what some have thought of as law is not really law at all.”

—Frederick Schauer ’72, professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, from “Law’s Boundaries”

What legitimizes the administrative state?

“What, if anything, legitimates the administrative state? By ‘legitimacy’ I refer not to any thick normative notion, but to sociological and public legitimacy—the ambient sense in the polity that, whatever grievous errors or injustices the administrative state may inflict in particular instances, its basic existence is acceptable, and the errors and injustices are jurisdictionally valid; they do not amount to reasons for rejecting the extant institutional arrangements altogether. In American legal theory there is a rich intellectual tradition—actually a field or domain of overlapping, conflicting, and competing traditions—that attempts to answer this set of questions about the administrative state, and the Harvard Law School has historically been central to the enterprise.”

—Professor Adrian Vermeule ’93, from “Bureaucracy and Distrust: Landis, Jaffe, and Kagan on the Administrative State”

On legislative intent

“Certainly, human beings routinely attribute intentions to multimember institutions such as sports teams, businesses, and armies. But when the questions get tough, those intentions are constructed, not real. Hence, in the case of statutory interpretation, the challenge is how to decide what should count as Congress’s decision and to determine what creative license judges should have to build upon or repair Congress’s handiwork.”

—Dean John F. Manning ’85, from “Without the Pretense of Legislative Intent”

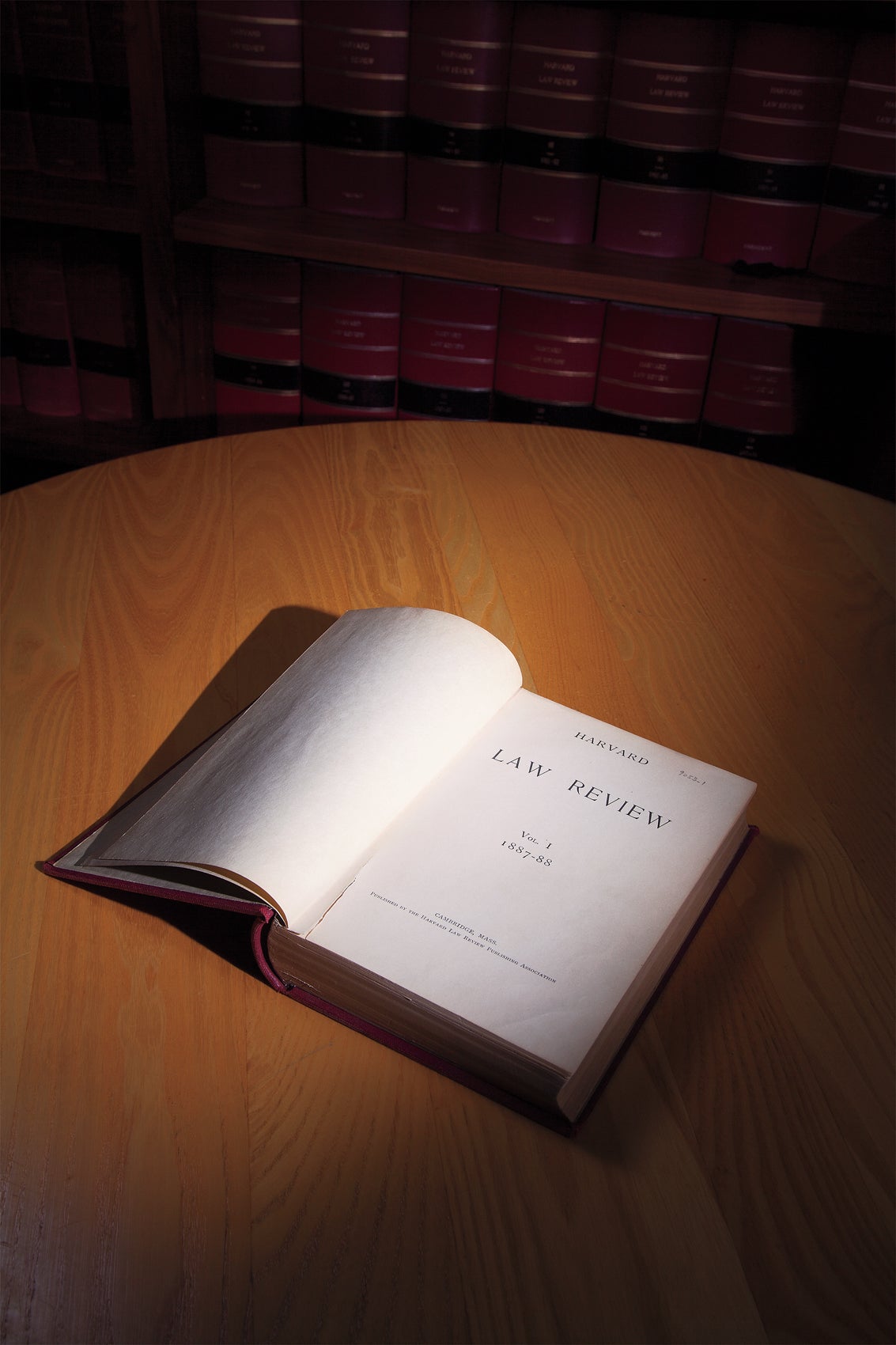

Read the entire Law Review Bicentennial issue.