The U.S. Supreme Court ruling mandating school desegregation in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 is considered one of the Court’s landmark decisions. But the implementation of federal law prohibiting state-mandated school desegregation required a subsequent ruling in 1958, in Cooper v. Aaron, in which the Court held that states could not avoid desegregation by legislative action.

In October, the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice sponsored a two-day conference looking back at Cooper v. Aaron and the impact it’s had on law and education over the course of 55 years. The event brought together legal scholars, students, and civil-rights lawyers and featured a moot court proceeding involving U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer and nine appellate judges, to revisit the legal questions raised by Cooper.

Another highlight of the conference was a presentation by four members of the “Little Rock Nine,” who, as teenagers, took part in an effort by the NAACP to break the racial barrier at Little Rock Central High School in 1957 and helped to pave the way for Cooper.

All four recalled the experience as a challenging one, requiring them to endure harassment from fellow students and the public. But they also remembered being committed to a cause of which they were well aware.

On the first day the students arrived at the school in early September, they were prohibited from entering by the Arkansas National Guard. They weren’t able to attend until later that month, after President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division.

Ernest C. Green, who currently serves as a partner in an asset management firm, remembers having doubts when he saw the National Guard standing in his way the first day. “But it didn’t take more than a minute to figure out that this was about more than our going to school, that this was a bigger issue. I didn’t know how big it was, but I knew that backing down and turning around didn’t seem to be an option.”

Terrence Roberts, who holds a Ph.D. in psychology and is on the faculty of Antioch University, said that “I’ve never experienced fear like I felt at Central High School.”

However, he said, he understood that the law was on his side.

“The Brown decision said we are legally able to do this. In a society that ostensibly obeys the rule of law, this was our opportunity. The other thing for me was that I had full knowledge of the number of people who had come before me and given their lives in this same struggle. No way on earth could I desecrate their graves by saying no.”

However, as Erwin Chemerinsky pointed out during the moot court oral argument, the degree to which student bodies have become racially mixed in many school districts has been far from encouraging. “Fifty-eight years after this court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, American public schools are increasingly separate and unequal,” said Chemerinsky, dean at the University of California, Irvine, School of Law and acting the role of counsel to two plaintiff students in the fictitious case, Oglethorpe v. Harris Wald Township.

The purpose of the exercise was to review the legal issues raised by Cooper v. Aaron in a contemporary setting reflecting the influence of such subsequent Supreme Court cases as Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle, in which the Court concluded that students’ assignments could not be based solely on race, even for racial balancing purposes. As the bench brief for the appellate judges noted, the result has been “re-segregated schools” that experience “large disparities in public funding.”

The fictional case, involving such a situation, was created to stimulate a discussion about the extent to which race may now be considered in any judicial remedy to achieve desegregation and whether desegregation can be “coterminous” with educational equity.

After Chemerinksy and HLS professor Nancy Gertner, as counsel to the defendant school district, presented their arguments, the justices engaged in public deliberation that revealed strong concerns about the degree to which courts now have the power to achieve desegregation.

“I think there is agreement that there is a compelling interest in diversity,” said Judge James A. Wynn, Jr., U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit. “The question then becomes: How do we achieve such a thing?”

Judge Roger L. Gregory, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, said he believes the emphasis must be on “finding ways to teach kids where they are.”

“Where schools are 99 percent African-American, are they to be condemned forever for being inferior? No; not at all. I don’t think anyone has really made the case that single-race schools are inherently inferior.”

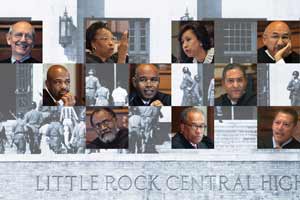

The justices listening to arguments

Reflecting on the reflective mood of the day, Judge Harry T. Edwards, U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, said that even though Brown and Cooper were momentous rulings, they were far simpler matters of law than those found in the current legal climate in which many black families are trying to get their kids out of low-performing poorer schools as well.

“I wish I knew what the answer is, but I don’t,” he said. “I do know that as a judge, there’s not an easy way for me to determine how to solve the social problems of the public schools with the legal principles that are now in place.”

But Justice Breyer sounded an optimistic note to conclude the proceedings: “When you start pointing out that there’s this tremendous discrepancy, that we are a democracy and we have human rights and we are comparatively rich as a country, people are going to start thinking more and more that this is not a normal situation.”

Oral Argument before Judicial Panel

Presiding Chief Justice:

The Honorable Stephen G. Breyer

Associate Justice, United States Supreme Court

Justices:

The Honorable Bernice B. Donald

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit

The Honorable Allyson K. Duncan

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit

The Honorable Harry T. Edwards

Senior Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

The Honorable James E. Graves

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit

The Honorable Roger Gregory

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit

The Honorable Raymond Lohier

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit

The Honorable Theodore McKee

Chief Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit

The Honorable Barrington D. Parker, Jr.

Senior Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit

The Honorable Ann Claire Williams

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit

The Honorable James A. Wynn

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit

Attorneys for the Parties:

Erwin Chemerinsky

Dean and Distinguished Professor of Law, University of California, Irvine School of Law, for the Petitioner Oglethorpe

Nancy Gertner

Harvard Law School, U.S. District Court Judge (Ret.), for the Respondent Harris-Wald Township