On a June day 800 years ago, King John of England met with disaffected feudal barons at Runnymede, a meadow on the River Thames 20 miles from London. Under pressure for overstepping his authority over landowners, the king put his seal to Magna Carta, the “great charter” that in 1215 was merely a summary of customary feudal rights and guarantees. But the charter went on to have a second life as an argument for liberty more generally, and as a primer on the rule of law. Soon Magna Carta shook the world into modernity with a feudal message readily recast as revolutionary: Executive power has limits.

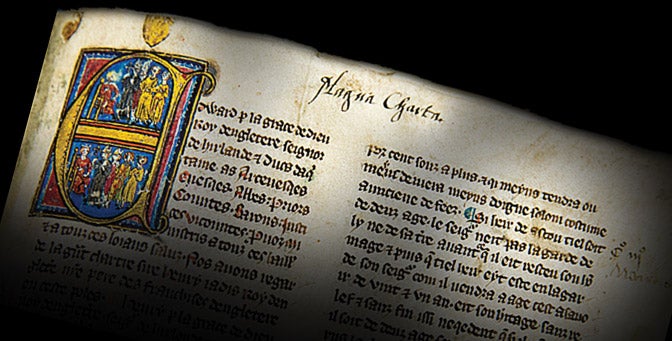

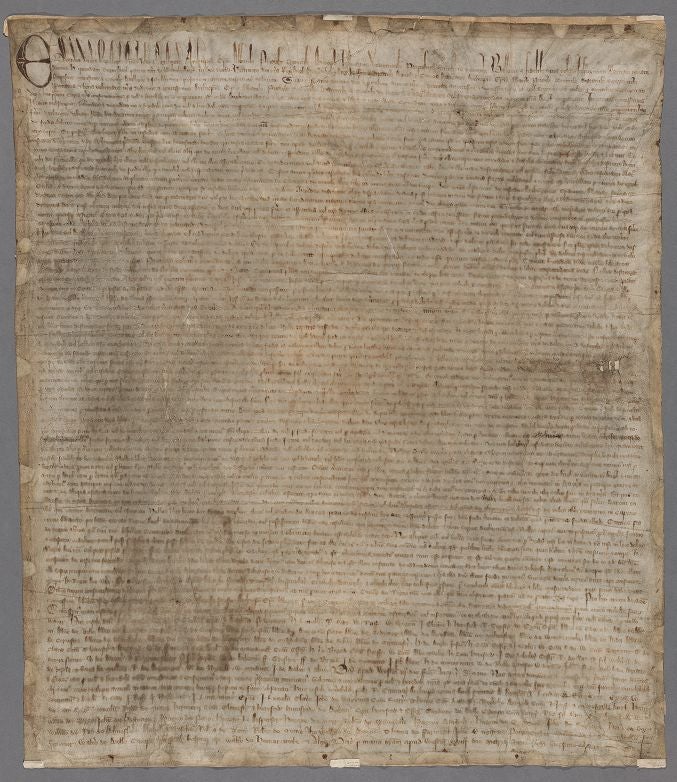

Handwritten in Latin on sheepskin parchment, the one-page charter drew “direct lines to some of our most fundamental principles,” according to the American Bar Association. (Included were due process, trial by a jury of one’s peers, punishments that matched crimes and habeas corpus.) Its 63 provisions also included demands for safe passage at borders, standardized measures for traded goods, fixed and independent courtrooms, fair interest rates, and the power of localities to make their own laws. HLS Visiting Professor Daniel R. Coquillette ’71 called it “our first great constitutional document” in his book “The Anglo-American Legal Heritage” (1999). Despite its not being a constitution or even legislation, he wrote, Magna Carta “remains a great symbol of the rule of law and of limitations on arbitrary executive power.”

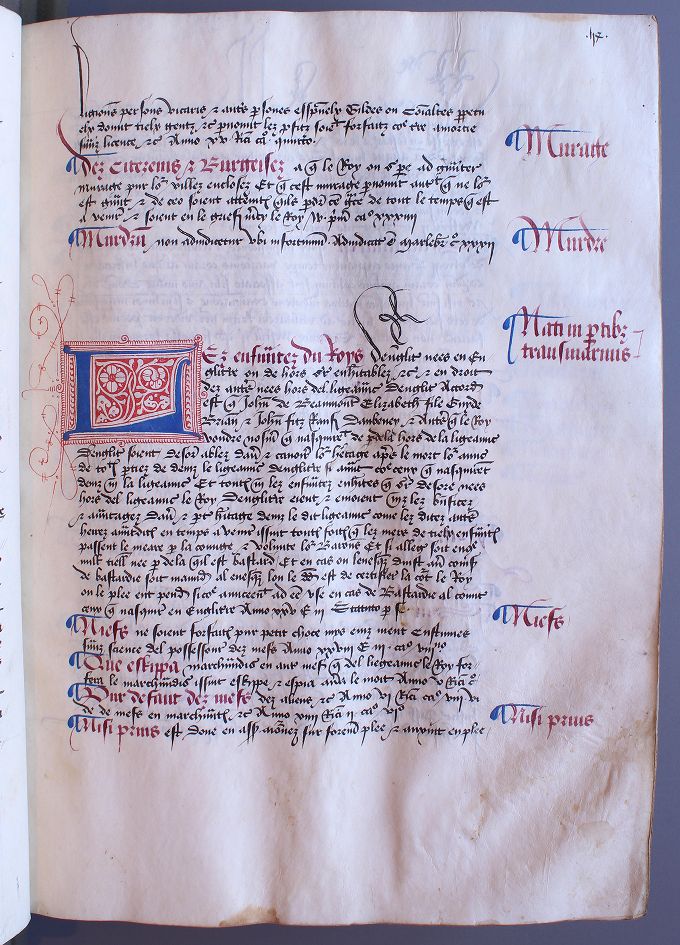

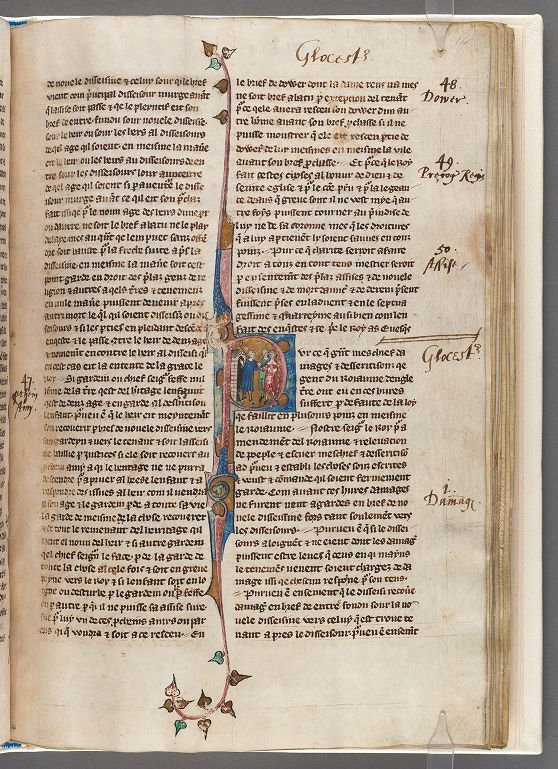

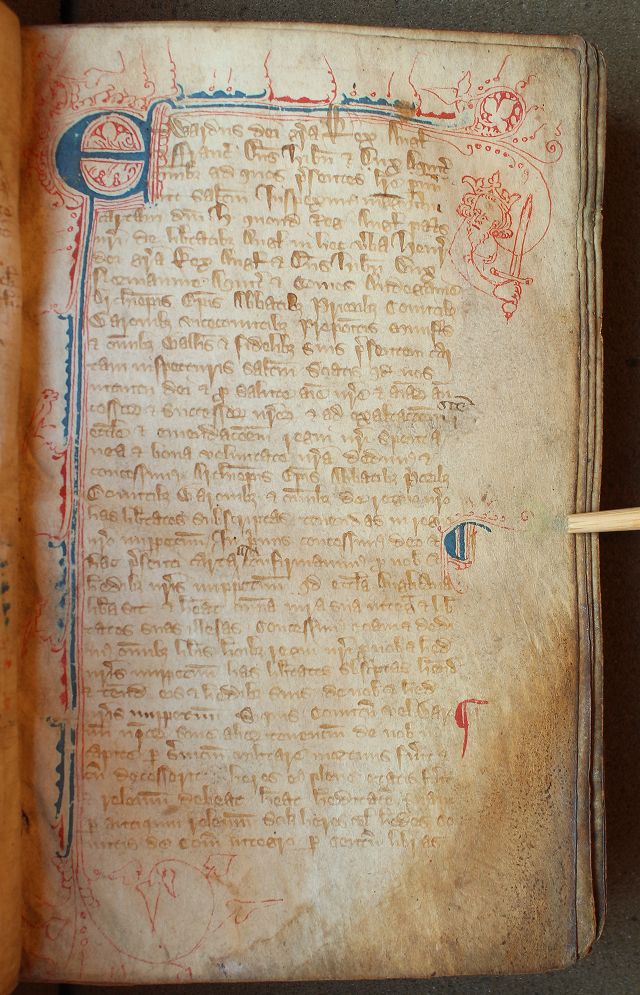

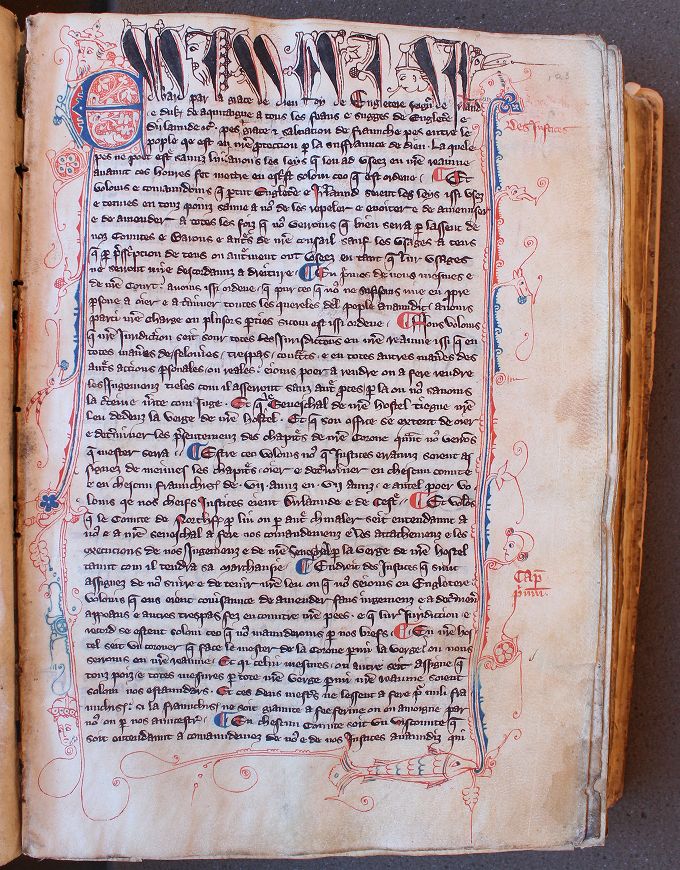

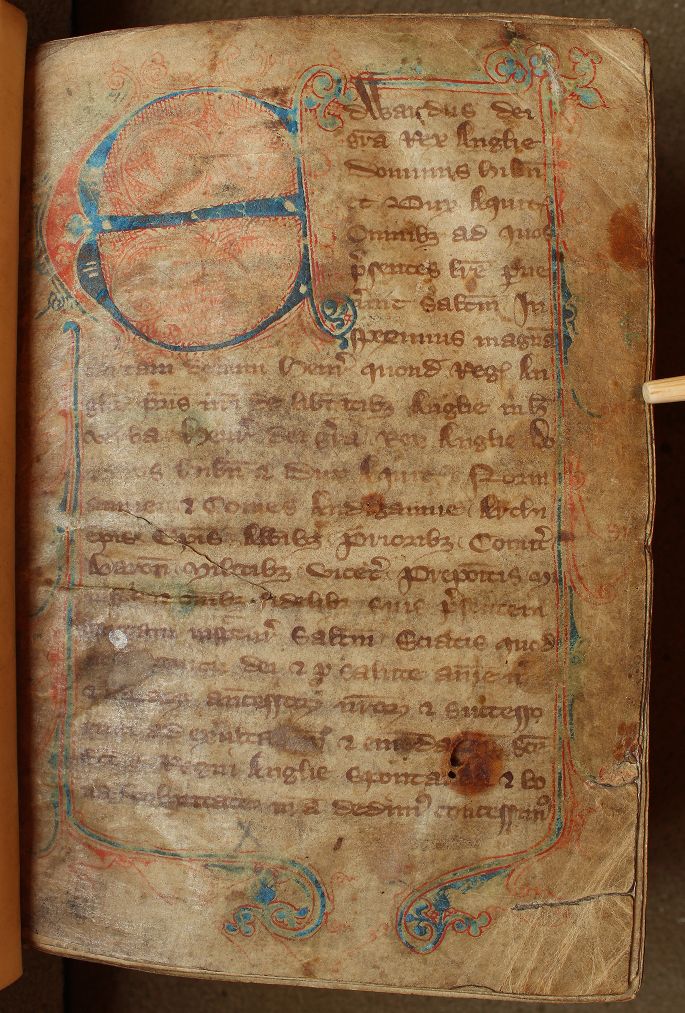

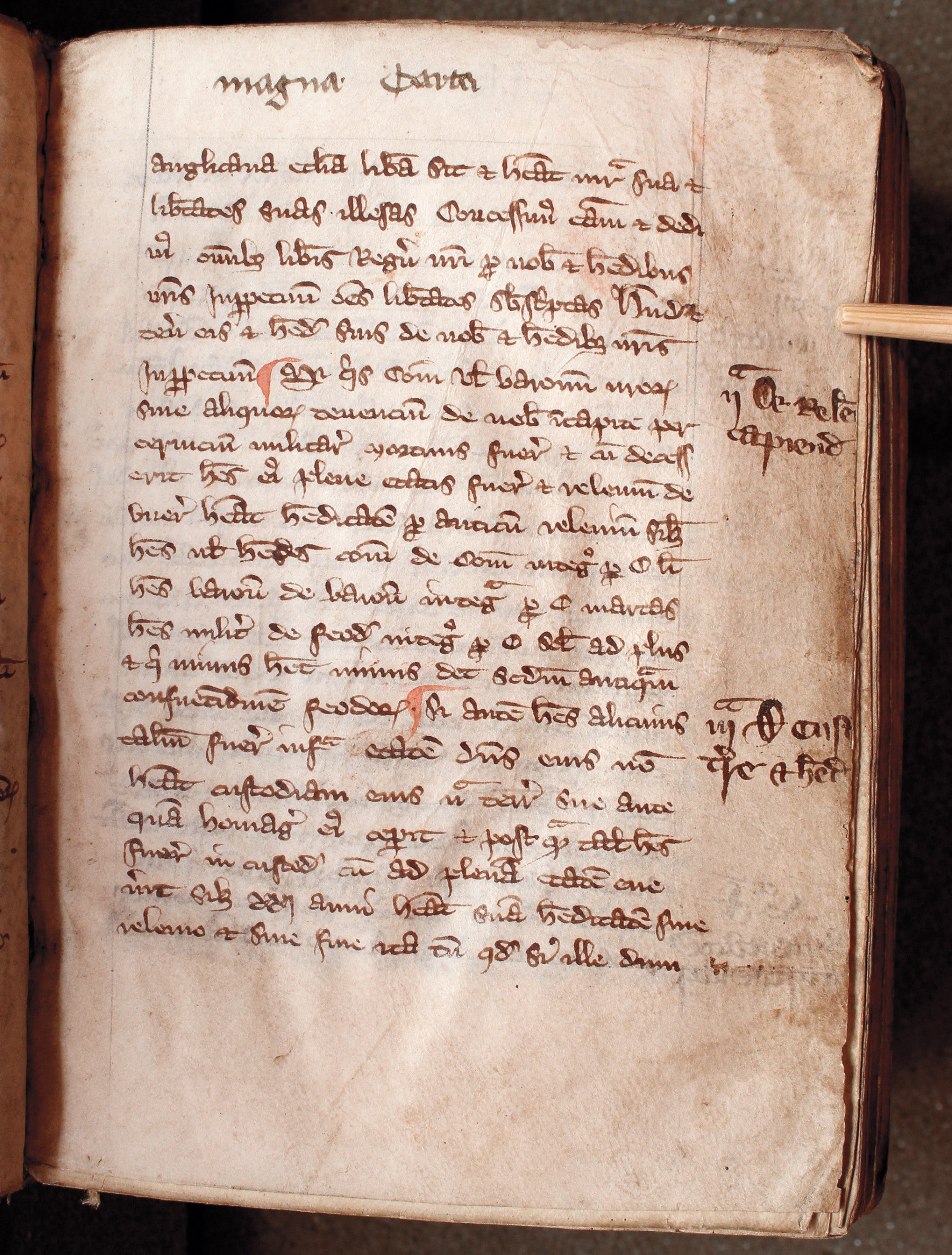

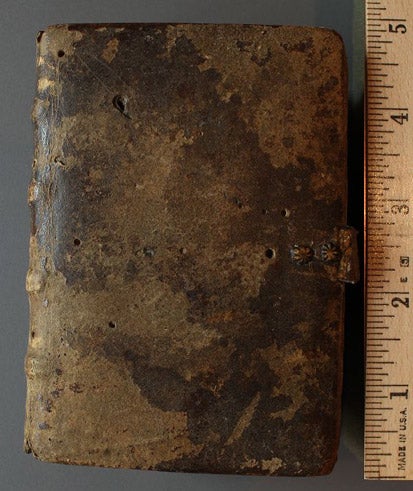

The Harvard Law School Library owns 39 early manuscript copies of Magna Carta (ca. 1300 to 1467)—and many printed versions. (A special exhibit is planned for the fall.) One example, a manuscript version of the abbreviated charter that was distributed to English sheriffs around 1327 , is said to have been read aloud four times a year.

Magna Carta’s 1225 version was integrated into English statute rolls in 1297, and then into law books during the 16th century. But only four of its provisions survive in present-day British law. HLS Professor Charles Donahue Jr. said that more provisions of Magna Carta are in effect today in Alberta, Canada, than in Great Britain itself. Despite its enduring power as a metaphor for liberty, Magna Carta “is not a charter of liberties or a bill of rights in either the modern or the 17th century sense,” Donahue told a recent class. But it was “a good start” on the primacy that individual grievances against authority would one day have, he said; it included provisions that “foreshadowed” the idea of a parliamentary petition; and it offered an early glimmer of what we now call the rule of law.

During the 17th century, Magna Carta inspired English Puritan rebels during “battles over the power of the king,” said Mary Sarah Bilder ’90, professor of legal history at Boston College Law School. For years after, she added, it “gets used as a way of arguing against authority.” The ancient text was invoked in the Virginia charter of 1606 and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties of 1641. Early colonists used Sir Edward Coke’s loose, colorful reinterpretation of Magna Carta as a template for laws in the New World.

John Adams used Magna Carta during arguments against the Stamp Act and the vice admiralty courts. In 1775, Massachusetts revised its seal to depict a man holding Magna Carta in one hand and a sword in the other, a version that survived until 1780. Magna Carta was used in the constitutions of at least eight of the original colonies, and its sentiments survive in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

At an American Bar Association gathering last summer, Chief Justice of the United States John G. Roberts Jr. ’79 said Magna Carta helped give rise to representative government, moderated executive authority and established the idea of an independent judiciary—vital today as a place of cool judgment, he said, within the heat of partisan debate. Last fall, at the Library of Congress, Roberts called Magna Carta a driving force behind the ideals that propelled American independence.

To this day, Americans are more “obsessed” with the centuries-old charter than the British, said Bilder. Americans regard it as symbolic of an idea woven into the fabric of the Constitution: that authority is not absolute. The American obsession—underscored by ABA pronouncements starting in the 1950s—may reflect a relatively new country seduced by the idea of such an old legal framework. “To be part of an 800-year-old tradition,” she said, “is somehow comforting.”

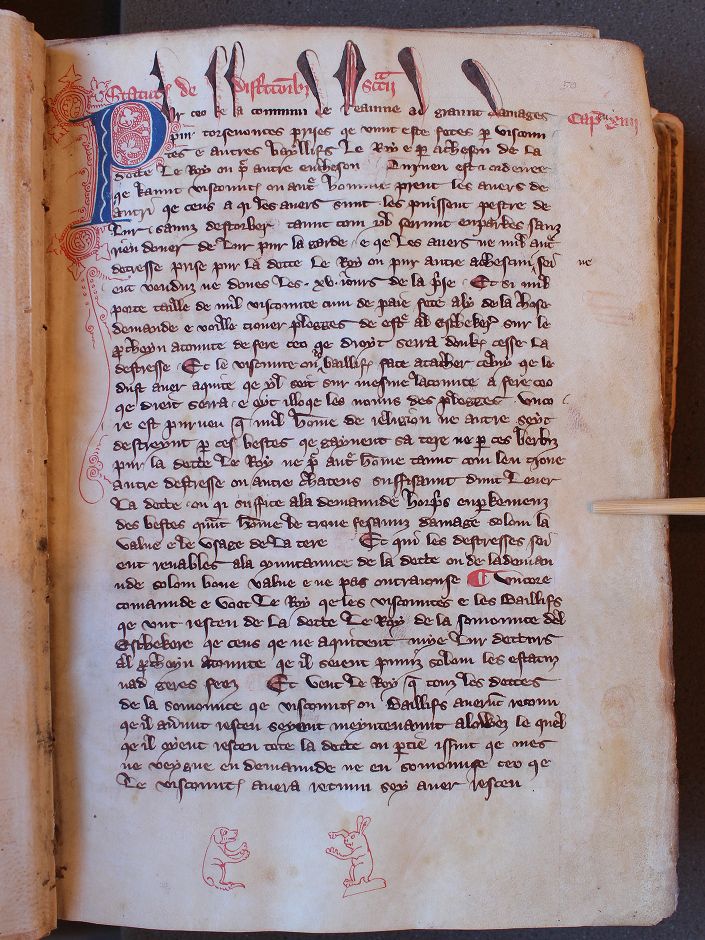

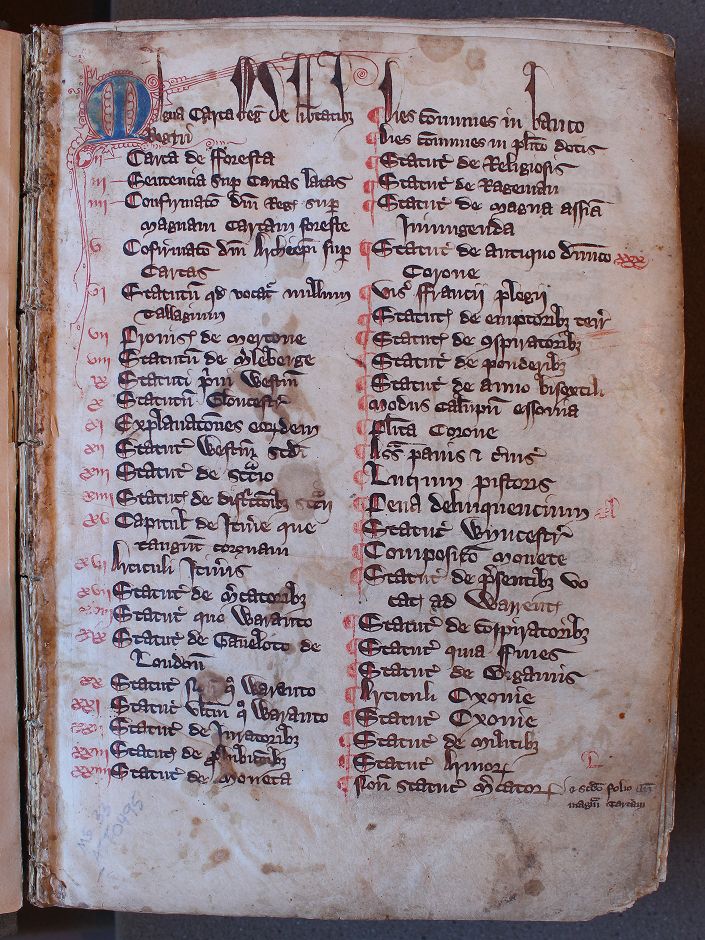

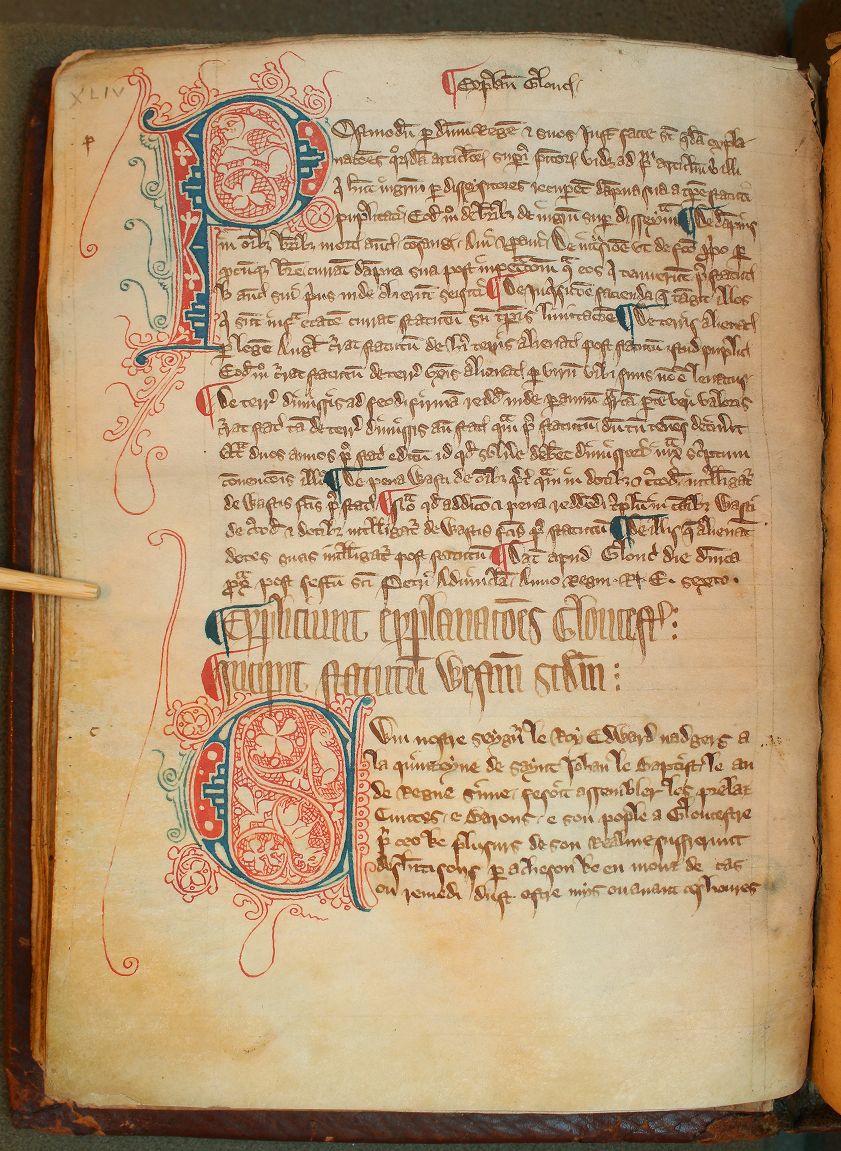

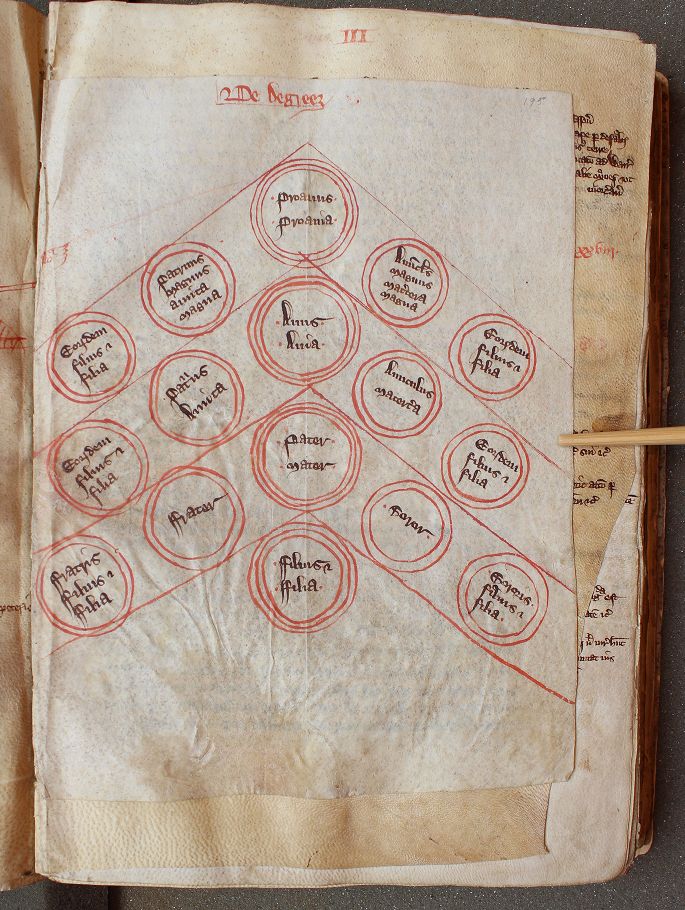

Picturing the ‘Great Charter’

The Harvard Law School Library Magna Carta collection includes manuscript copies dating from 1300 to 1467, many of them annotated and illustrated. To celebrate the 800th anniversary of the charter, the HLS library in conjunction with the Ames Foundation recently digitized these texts (along with its entire collection of statutory manuscripts from the period). Flip through some of the more colorful pages from the school’s Magna Carta collection.