In what has become a Harvard Law School tradition, First Class, an organization started by Harvard Law students to offer community and resources for low-income and first-generation college students, hosted a welcome reception for incoming students in August.

HLS First Class executive co-directors Kimberly Foreiter ’22 and Deanna Krokos ’22 kicked off the Third Annual First Class Reception as a virtual event during this year’s J.D. orientation. Logging in over Zoom, incoming students met members of the First Class community and listened to welcome remarks from First Class leadership and HLS administrators.

“You have so many firsts ahead of you, and it may all seem uncertain,” said Krokos, who has been involved with the organization since her 1L year. “Two years and two days ago, I was working my last closing shift after six years of waiting tables, wondering if I have what it takes to get through this place. But let me be among the first to tell you, you’ve come to HLS with everything you need.”

“First Class is a family,” said Foreiter, the daughter of two working-class South American immigrants. “[It’s] most definitely a place for you to come as you are and be celebrated for every mountain you climb.”

First Class board member and Director of Climate Juan Espinoza ’21, from the Coachella Valley in Southern California, concurred. “Welcome to what, I think, is one of the most special communities at HLS and an organization that I’ve come to love so much because it’s a place where I can fully be myself, where we can be in community, where you can look other people in the eye and know that they understand how hard you fought to be here and the burden and the hurdles that you faced to get to where you are,” he said.

First launched in 2017, First Class focuses on building community among first generation and low-income students, advocating for resources and support, and creating additional mentorship opportunities with faculty and alumni. The organization currently has more than 200 members.

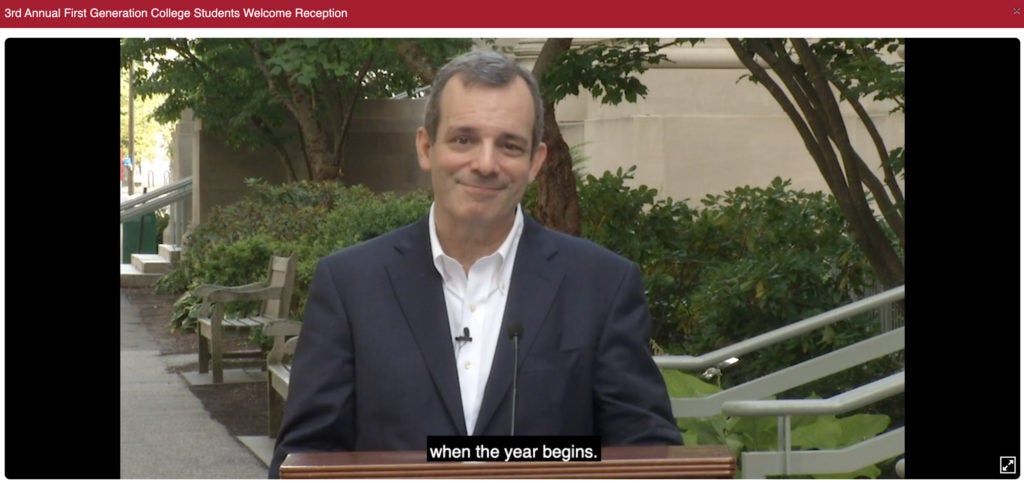

Harvard Law School Dean John F. Manning ’85, a first-generation student, said he is proud to be a member of this remarkable community.

Manning—whose father died when he was 10 and whose mother struggled to support their family—said when he was growing up the world of higher education was “entirely foreign” to him. But, he said, the education he received at Harvard College and later Harvard Law School enabled him to live a life that neither he nor his parents nor theirs could ever have imagined.

“To me, it feels vital for this law school to continue to play that role, from generation to generation, to enable people to live new dreams, to find new paths, to bring new perspectives and ideas, and to contribute in new ways to making our community and our world better,” said Manning.

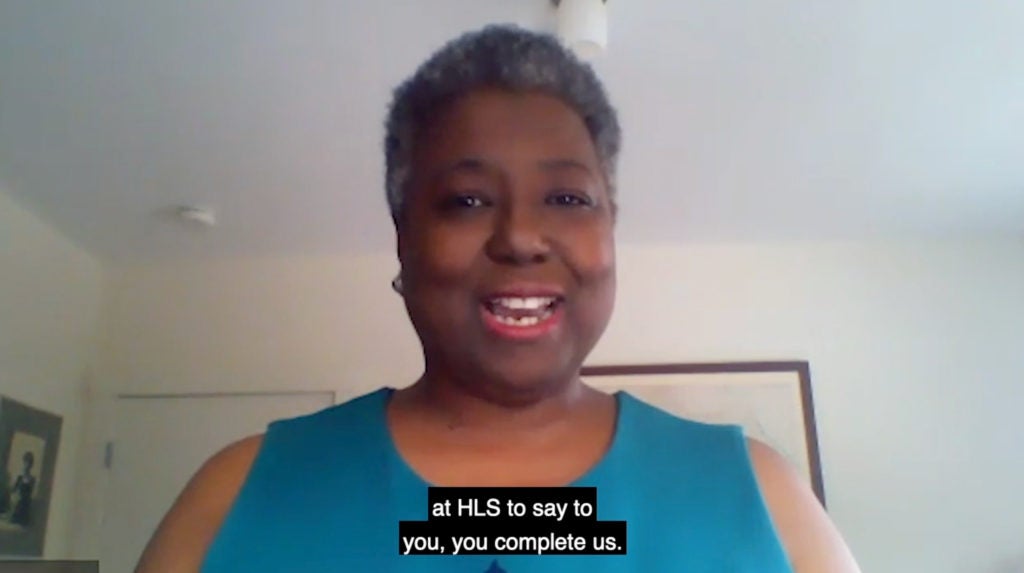

HLS Dean of Students Marcia Sells told the incoming class: “You complete us. … We would not be the same place or fully formed without you,” she said. She urged students to take advantage of the support HLS faculty, upper-level students, and administrative offices—from the Dean of Students Office to Legal Research and Writing to Career Advising—have to offer. “You have every opportunity at HLS to grab the reins and control your destiny in school and beyond,” she said. “We are right here to support you and lift you up.”

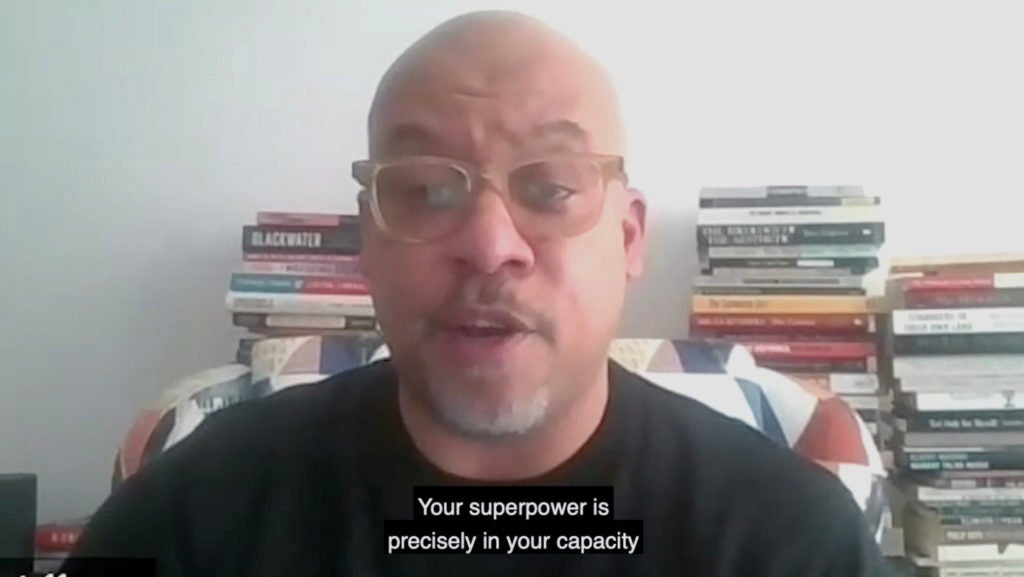

Mark Jefferson, assistant dean for community engagement and equity at HLS, and a first-generation college student who graduated from the University of Michigan Law School, told the incoming class to embrace and draw strength from the unique life experiences that brought them to HLS.

In a moving keynote address, Jefferson shared lessons he learned in his recent attempt to make his mother’s most prized family recipe: cornbread. “The kind of cornbread prepared by love that always reminds me that I was prepared for everything I’ve encountered in my life by the love of my family,” said Jefferson.

After learning that the legendary recipe was never actually written down, Jefferson tried to reconstruct it in a phone consultation with his mother. Instead of standard units of measurement, her instructions to “eyeball” the vegetable oil and look for a “sheen” on the batter led to a hilarious exchange filled with love and laughter. His mother signed off the call by telling him how proud she was that her recipes would now live on through him.

Jefferson said when he recalled their conversation later, he found himself overwhelmed with emotion.

“What moved me to tears the next day was the realization that my mom, Nanita Cheryl Mason and her mom, Annie Raye Arnold, and her mom, Victoria Simms, and her mom, Mildred Joyner, had spent their lives working with incomplete recipes,” said Jefferson. “That the world into which they were born—one into enslavement, three into the Jim Crow South—was a world designed to break their bodies and their spirits; a world that constantly told them that the lives they were supposed to live would not have a sheen or a shine to them. And they, rather than believe the world, fashioned their own—kept a steady eye on life’s ingredients, and mixed those ingredients, whatever they were and however unfair and unjust, until they found the sheen, until they were able to create lives that shined. And then they passed it on.”

Nothing in this life worth having is ever given to you, he said. “Your superpower is precisely in your capacity to keep your eyes on the ingredients that life has given to you, to identify and secure the ingredients and directions that are missing, and to mix the stuff of your lives together until you find what shines.”