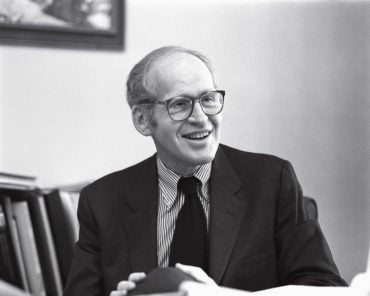

Several years ago, Alan Stone asked me to co-teach a course with him. When I asked what we should teach, rather than give explicit direction, he said with a broad smile on his face: “Let’s teach what is fun for us! If we have fun, the students will have fun and they will learn.” As Alan approaches retirement at the end of June, I think this anecdote illuminates his joyful and generous journey—as a teacher, a listener and a leader across disciplines.

In Alan’s classes, his delight in teaching is palpable, and the topics can be startling. I remember as a 2L that discussion in his courses seemed different than in my other classes. It was not only a dialogue about doctrines and arguments but a vehicle to go beyond the law into culture, politics, and sometimes, ultimately, the moral challenges and meaning of life. At a time when barriers between outside disciplines and the law were breaking down, it was not unusual in an Alan Stone class to hear him discuss Kant, Freud, and the psychological motivations behind an opinion. Then he would shift into a practical discussion of the economic consequences of an opinion or the underlying policy issues. I remember vividly his analysis of Justice Brennan’s dissent in Cruzan. Alan argued that, beyond the manifest content, one could discern Brennan’s latent fear of his own death. In addition to learning the law, my classmates and I were asked to consider the moral and existential implications of what we were studying, and to apply these to ourselves as well as to society, always guided and prodded by a smiling, enthusiastic, and, above all, fascinated teacher.

Trained in psychiatry and psychoanalysis, Alan was a tenured professor at Harvard Medical School and director of the McLean psychiatric residency when, in 1965, Alan Dershowitz invited him to co-teach Psychoanalytic Theory and Legal Assumptions at HLS. The course was a hit and inaugurated a long friendship between the two men, who next taught Psychiatry and the Law together. In 1968, Alan obtained a yearlong sabbatical to study law, and this experience helped him to find his “intellectual home” at the law school. Shifting his primary focus from the medical school to HLS, and seeing a need for a law and medicine curriculum, Alan eventually taught the Psychiatry and the Law and the Psychoanalytic Theory courses on his own. (In the latter course, which I took, we read more Freud than I had anywhere else at Harvard.) He also taught Clinical Dimensions of Mental Health Law and the extremely popular Law and Medicine, among others. Since 1982, he has been the Touroff-Glueck Professor of Law and Psychiatry in the faculties of law and medicine.

Over his 50-year career, Alan has become fast friends with many HLS colleagues, meeting for congenial meals and reading groups, sharing ideas about such topics as philosophy, history, and civil rights. During that time, Alan’s courses have expanded to cover topics including law and literature, film, and violence. They are popular and often oversubscribed, such as Justice and Morality in the Plays of Shakespeare. (Alan has regularly staged a trial of Hamlet, sometimes with Justice Kennedy presiding.) Recent offerings include teaching concepts of identity through the works of Philip Roth and the short stories of Alice Munro.

“In Alan’s classes, his delight in teaching is palpable, and the topics can be startling.”

Alan’s writings encompass over 100 books, chapters, and articles, many of which have been influential in the legal and medical professions, some directly influencing Supreme Court opinions. His landmark book “Law, Psychiatry, and Morality,” for example, explores how moral reasoning can elucidate problems of law, ethics, and the treatment of the mentally ill and has been widely read and cited. His interests are too many to mention but have included the right to treatment, economics of the medical profession, ethics of forensics, right to die, and political misuse of psychiatry. He is also a contributor to the Boston Review and has collected his film reviews from that publication in “Movies and the Moral Adventure of Life.” His book “The Abnormal Personality Through Literature” has had 22 printings.

Alan remains active in our nation’s political and cultural life, often arriving at positions both unexpected and controversial. A past president of the American Psychiatric Association and a former member of its board, he successfully lobbied to have homosexuality removed from the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.” On the Waco Commission, he was the sole dissenting member, critical of the government’s assault. His examinations of Soviet and Chinese psychiatry have resisted simplistic dismissals of his colleagues there. And his 1995 address to the American Psychoanalytic Association argued that while analysis has failed as a treatment for mental illness, it can still relieve our “ordinary suffering,” a courageous and unpopular position.

When I asked Alan to name his major accomplishment at HLS, he said “to bring humanism to the law school.” This seems apt. Certainly, by expanding the curriculum, he expanded our conceptions of not only the law and its actors, but also what it means to be human. But perhaps as important, Alan is extremely generous, kind and, I would say, humane. I have been privileged to be his student and research assistant and to teach several reading courses with him, and I marvel at how skillfully he guides students, gently prodding and exploring with them, encouraging not only the class superstars but also the more timid or struggling. Alan invites students to join him in intellectual inquiry and is more interested in understanding a student’s point of view than in getting him or her to agree with him. He delights in engaging his colleagues and friends at HLS, too, often greeting them with warm words of encouragement and praise in the dining room, in offices, or even passing in the elevators.

Alan’s open and receptive persona has earned him the trust of many students beyond the classroom. Some have sought his advice when confronted with difficult problems in school or their personal lives. I myself have repeatedly consulted him regarding my own career choices and teaching decisions. His approach is not to reach a predetermined conclusion or tell me what to do. Rather he says what he thinks and supports my capacity to ask myself hard questions and answer them honestly. Alan believes that the meaning of life is to be found in answering, or attempting to answer, the moral challenges life poses. Such an endeavor requires what he calls “moral courage.” And by modeling this courage in his own life and career, Alan teaches that, while one may not find the expected or desired answers—or even be satisfied or happy with them—one will certainly be alive.

Duncan C. MacCourt ’94 is an associate medical director at McLean Hospital, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and a lecturer at Harvard Law School.