A sharp increase in web encryption and a worldwide shift away from standalone websites in favor of social media and online publishing platforms has altered the practice of state-level internet censorship and in some cases led to broader crackdowns, a new study by the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University finds.

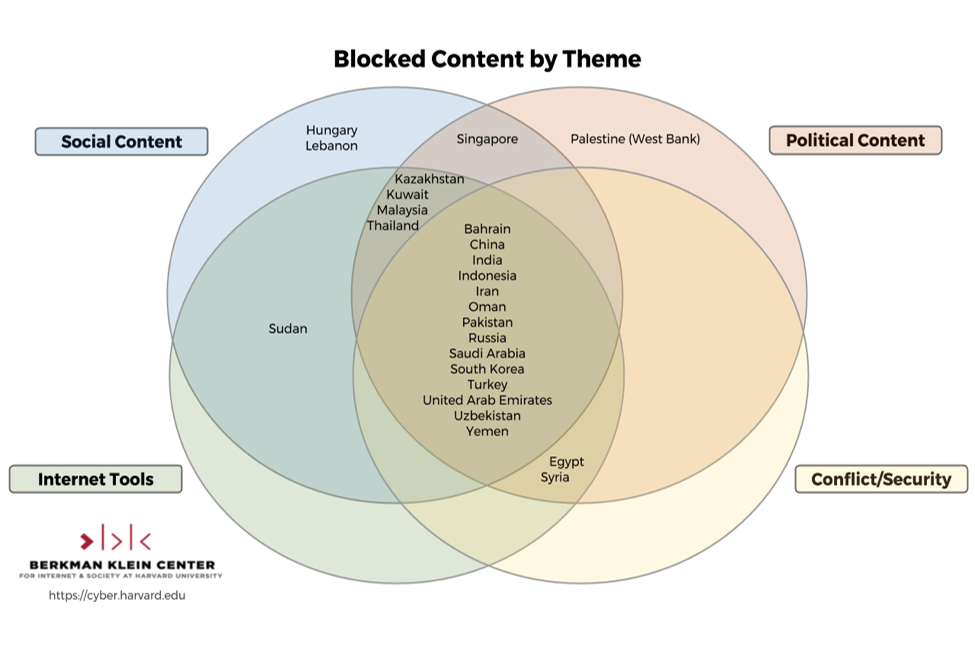

“The Shifting Landscape of Global Internet Censorship”, released today, documents the practice of internet censorship around the world through empirical testing in 45 countries of the availability of 2,046 of the world’s most-trafficked and influential websites, plus additional country-specific websites. The study finds evidence of filtering in 26 countries across four broad content themes: political, social, topics related to conflict and security, and internet tools (a term that includes censorship circumvention tools as well as social media platforms). The majority of countries that censor content do so across all four themes, although the depth of the filtering varies.

The study confirms that 40 percent of these 2,046 websites can only be reached by an encrypted connection (denoted by the “HTTPS” prefix on a web page, a voluntary upgrade from “HTTP”). While some sites can be reached by either HTTP or HTTPS, total encrypted traffic to the 2,046 sites has more than doubled to 31 percent in 2017 from 13 percent in 2015, the study finds. Meanwhile, and partly in response to the protections afforded by encryption, activists in particular and web users in general around the world are increasingly relying on major platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, Medium, and Wikipedia.

These trends have created challenges for state internet censors operating filters at national network levels. When an entire website is encrypted, it is not easy to detect and selectively block a particular dissident’s page on Facebook or troublesome history lesson on Wikipedia. So unless a platform agrees to remove content, a country must either block the whole site, or allow everything through.

“Twenty years ago the web’s infrastructure was truly distributed; ‘visiting a web site’ could mean corresponding with a server in a university, a private home, or a business anywhere in the world. Today, content and services are increasingly hosted among a handful of cloud providers,” says Jonathan Zittrain, professor of computer science and George Bemis Professor of International Law at Harvard University and a co-founder of the Berkman Klein Center. “That may have helped standardize the rollout of encryption for day-to-day communication over the web, while at the same time placing the major providers under increasing pressure to shape and censor their services by governments in markets where providers wish to have a strong physical presence.”

In some respects, the shift may be reducing the blocking of communications. For example, in 2011, Saudi Arabia was blocking individual Wikipedia entries (such as one describing the theory of evolution); and individual Twitter accounts such as that of Egyptian activist Wael Ghonim, with nearly 2.8 million followers, and the human rights advocate Gamal Eid, the director of a Cairo-based regional human rights NGO. But today both of those sites use HTTPS, making such censorship practices difficult. While Saudi Arabia vigorously censors many types of content, it doesn’t block Wikipedia or Twitter, which in effect allows these critics to be heard in the Kingdom.

But in other contexts, the shift has been followed by broader crackdowns. For example, in recent years Medium, the online publishing platform, has become popular among activists in Egypt. But in June 2017, Egypt blocked Medium, effectively censoring not only the activists’ content but also millions of other articles on the site. Similarly, Malaysia blocked Medium in January 2016 after the company refused to take down articles about a government corruption case.

And in April of 2017, Turkey blocked all of Wikipedia because censors could not block (or convince Wikipedia to remove) entries asserting that Turkey sponsored terrorist organizations. This left Turkey’s population without any access to Wikipedia’s 290,000 Turkish-language entries. “Tech companies are on the front lines; to an ever-greater extent they serve as the principal guardians of freedom of expression online around the world,” says Rob Faris, a co-author of the report and research director at the Berkman Klein Center.

Among the report’s many other findings is that governments are increasingly blocking content from other governments, not merely blocking internal dissidents and other non-state actors. This is particularly evident in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) countries.

In a related trend, the MENA region is also experiencing a rise in shared internet censorship practices among allied nations. For example, Saudi-allied countries have begun to block the same websites originating from Qatar. “State internet censorship practices are increasingly intertwined with intraregional political dynamics,” says Helmi Noman, a report co-author and research affiliate at the Berkman Klein Center. “The regional political tensions and conflicts and political alliances around them give rise to bloc-centered similar internet censorship policies,” he says. “As a result, more states now ban content originating from or affiliated with rival states.”

Of course, governments have other means at their disposal to suppress online speech, including arresting dissidents, pressuring companies to take down content, and shaping online narratives by launching disinformation campaigns on social media platforms.

The Berkman Klein Center report is the latest of several studies and media reports from the past year documenting global censorship practices. Governments have also blocked encrypted mobile messaging apps like WhatsApp and Viber that allow users to spread information quickly and securely, and even shut all internet access within national borders at certain times.

Regimes that aggressively filter the internet typically use third parties — usually private companies that specialize in selling filtering technologies — to detect and carry out content blocking. State censors have extended the reasons and rationales for internet censorship. The fight against terrorism has provided one justification for expanding political censorship, and states have exploited this to target political speech they find offensive. More recently, state censors have started using claims of “fake news” as motive to censor the internet.

For more information and to download a copy of the report, visit the Berkman Klein Center website.