When the U.S. Supreme Court issued an order just before midnight on September 1 that maintained Texas’ enactment of the most restrictive abortion law in the country, the public reactions that followed focused not just on the “what” of the Supreme Court’s order, but perhaps as importantly, the “how.” The majority opinion was unsigned, consisted of a single long paragraph, and was issued without full briefing, oral argument, or deliberation among the justices. It was the latest blockbuster use of the Supreme Court’s little-watched but increasingly important emergency powers, otherwise known as its “shadow docket.”

The “shadow docket,” a term coined in 2015, encompasses thousands of decisions made annually by the Supreme Court through a truncated decision-making process, sometimes released late at night in one- or two-sentence orders that often obscure how the justices voted or why the majority came to the conclusions that they did. These cases stand in contrast to the traditional merits docket, in which the Court reviews extensive briefs from the parties and other advocates in approximately 70 cases per year, generally hears oral argument, engages in a full deliberation among the justices, and ultimately issues binding, precedential decisions that outline the Court’s reasoning.

The Supreme Court has long issued short, procedural orders that generally have the effect of pausing lower court proceedings, but in recent years, this power has garnered increased attention and criticism. “The emergency orders docket provides a way, when necessary, for the Court to preserve the status quo,” explains Tejinder Singh ’08, an instructor for the Harvard Supreme Court Litigation Clinic and partner at Goldstein Russell, a firm that specializes in Supreme Court practice. “It is a necessary component of the Court’s ability to deal with and decide cases, and it is also one that we’ve seen more frequently getting used and abused both by litigants and in some cases the Court to make law without going through the Court’s usual plenary review processes,” Singh says.

The Court’s increasingly visible use of its traditionally hidden powers

Although the bulk of the shadow docket consists of orders that are both substantively and procedurally banal — extending deadlines, for instance, or denying petitions for review in routine matters — the ones that garner significant attention generally fall into two categories: cases in which a party seeks to uphold or challenge a newly enacted federal law, and last-minute requests for stays of execution.

The emergency orders docket provides a way, when necessary, for the Court to preserve the status quo.

–Tejinder Singh

For those who suspect that matters of national importance are cropping up more frequently on the shadow docket than in the past, the numbers bear out their observation. In four years, the Trump administration filed 41 emergency applications in the Supreme Court, compared to a total of only eight in the 16 preceding years in which presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama ’91 were in the White House. Those cases touched on multiple matters of national significance, including COVID-19 restrictions in places of worship, the death penalty, the national census, immigration policies, and a ban on transgender troops in the military.

According to Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus ’79, the Trump administration’s eagerness to turn to the Supreme Court was almost certainly inspired by a particularly shocking decision issued toward the end of the Obama presidency. On Feb. 9, 2016, the Court delivered an emergency order blocking the implementation of the Clean Power Plan, an Environmental Protection Agency regulation that would have required a 32 percent reduction in U.S. carbon emissions by 2030.

In a 5-4 decision marking the last time Justice Antonin Scalia ’60 cast a vote before his death four days later, the Court for the first time in history agreed to block implementation of a federal regulation before any federal appeals court had reviewed it, and after the D.C. Circuit had already declined to issue the requested stay. Because the Trump administration then abandoned the Clean Power Plan, the matter never reached the Supreme Court on the merits, and the regulation died without ever going into effect.

According to Lazarus, this decision signaled a sea change. “Lawyers are asking for the Court to exercise significant rulings in the context of the shadow, in a way they never did before, because they got a signal that the Court is willing to do it,” Lazarus explained.

Lawyers are asking for the Court to exercise significant rulings in the context of the shadow, in a way they never did before.

–Richard Lazarus

Likewise, says Harvard Law Professor Carol Steiker ’86, the Court has in recent years used the shadow docket to make momentous, literally life-altering decisions involving individuals seeking to avoid or alter the terms of capital punishment. The Court has long been the last possible stop for petitioners who have exhausted all other appeals, and midnight emergency orders either halting executions or allowing them to continue are not inherently new.

But Steiker argues that a major shift has occurred in the last few years, culminating in a series of surprising interventions at the end of the Trump administration, when the executive branch executed 13 people during its last six months in office — more people than had ever been executed in a single decade. In five cases, the executions took place only after the Supreme Court vacated decisions by lower courts that would have delayed the executions.

According to Steiker, the most jarring case involved Dustin Higgs, the last person to be executed by the federal government. There, the Supreme Court used the highly irregular procedure of agreeing to consider the case on the merits before judgment and summarily reversed a district court order that would have stopped the execution. No explanation was provided for the unusual move. “The lower courts wanted to take the time to have full briefing and argument and decide, and the Court not only didn’t do that itself, but it didn’t let the lower courts do that either,” Steiker explains. “That really raises a lot of concerns, especially when someone’s life is on the line.”

Steiker cited empirical research undertaken by one of her former students, Isaac Green ’22, in which he concluded that the Court has, in recent years, indeed drastically increased its interference with stays of executions granted by lower courts. Green’s analysis, which he plans to publish as a student note, connected this rapid escalation to the new Supreme Court conservative majority’s concern with avoiding gamesmanship and delay by those facing execution.

The Supreme Court, through its shadow docket in a number of Trump cases, did not allow litigation of a number of substantial constitutional and statutory issues raised in those cases.

–Carol Steiker

But as Steiker notes, many issues involving the death penalty—such as challenges to execution protocols and determinations of mental competency for execution—cannot be litigated until shortly before an execution is scheduled to occur.

“The Supreme Court, through its shadow docket in a number of Trump cases, did not allow litigation of a number of substantial constitutional and statutory issues raised in those cases,” she says. “The Court takes a very, very dim view of motions for stays of execution because a majority of justices attribute it, largely erroneously, to attempts at strategic delay by the defense bar.”

The shadow docket draws backlash

It is widely recognized, says Lazarus, that emergency orders are a poor way to make law. “No one thinks the justices should be deciding significant things based upon very limited briefing, no oral argument, and no meaningful deliberation,” he says.

But Lazarus argues that while it is easy to criticize the Supreme Court for using truncated procedures in controversial cases, that criticism tends to ebb and flow depending on the substantive impact of the decision being made by the Court. “If you read people’s reactions when the Court does this, they only complain if their ox is being gored,” Lazarus says.

Had the Supreme Court immediately acted in the Texas abortion case to enjoin the Texas law, Lazarus posits, pro-choice proponents, who brought the emergency petition to the Supreme Court, would have heralded the Court’s action as an appropriate means for the Supreme Court to step in in response to an outrageously unconstitutional state law, even though the Court would have done so without full briefing, oral argument, and deliberations. “It’s easy to say that this is not the right way to make decisions, but sometimes we like it, because we think what happened in the courts below is just outrageous.”

Singh agrees that critics of the shadow docket may well be fickle in the short term, but is concerned by the potential long-term impact of the Supreme Court increasingly weighing in on controversial matters before they can be fully litigated. “The Court’s credibility is on the line as its decision-making processes get diluted,” Singh says.

Singh is concerned that the use of the shadow docket in areas of significant public debate can undermine faith in the Court’s role as a trustworthy, neutral arbiter. When all the Supreme Court is doing is “pressing pause” on lower court litigation, Singh says, its role generally remains uncontroversial. But when the Court ventures into areas of law with significant national interest and actively interferes with the status quo, Singh says, its role is more precarious. “The reason the shadow docket sounds so ominous is because it smacks of secret decision-making processes that are far less transparent,” says Singh.

Both Singh and Lazarus pointed to the Supreme Court’s decisions in a series of cases involving COVID-19 restrictions in places of worship, in which the justices intervened to lift restrictions on the basis that they violated the First Amendment, as examples of the perils of the shadow docket. According to Singh, in those cases, the Court actively created new law that was more favorable to religious institutions than found in any Supreme Court precedent decided on the merits docket. “The most significant risk from shadow docket decision-making is that the Court’s one claim to transparency and accountability will be undermined when you have major decisions made with very little process beforehand.”

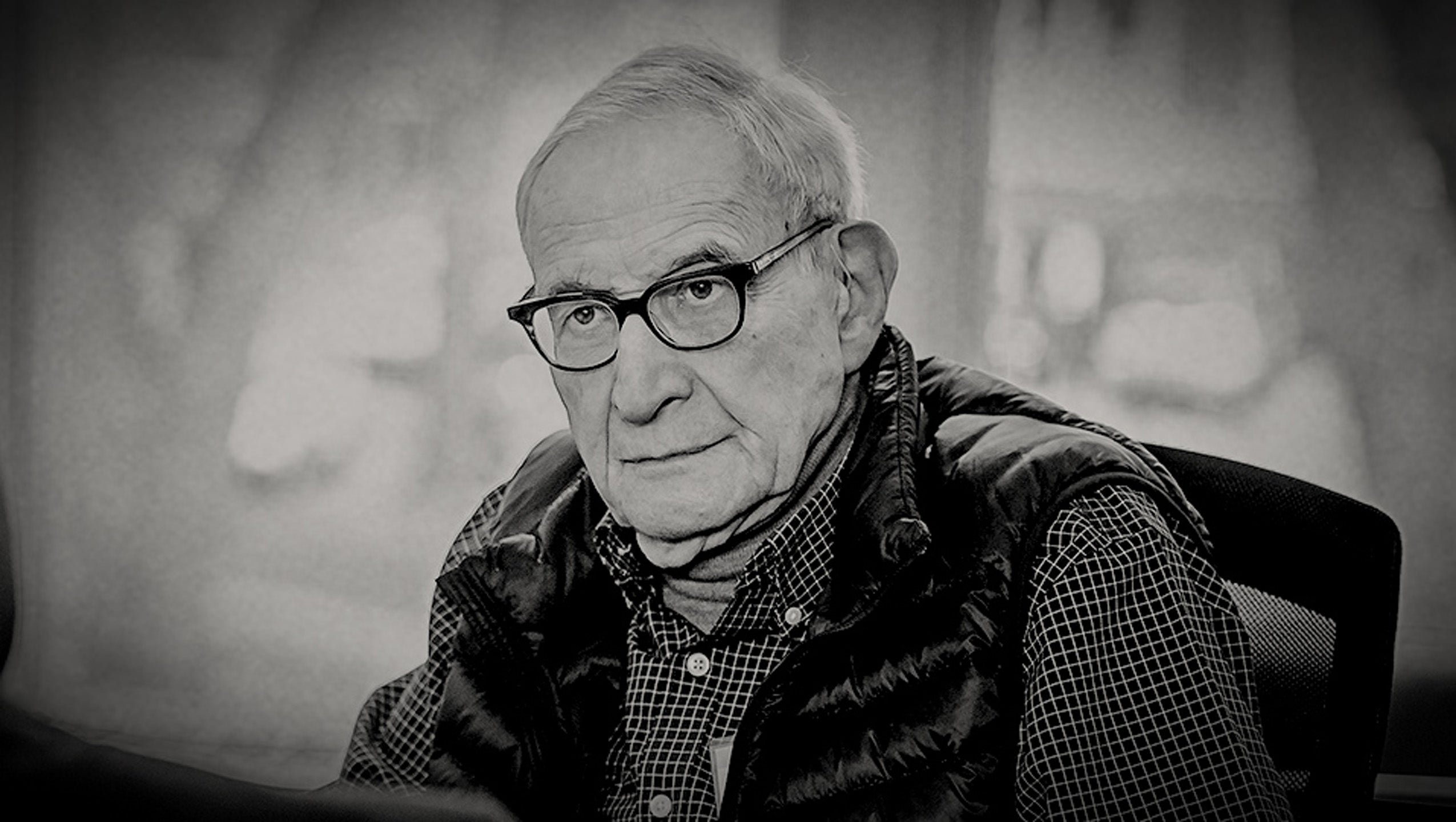

Professor Charles Fried Credit: Harvard Law School

Harvard Law Professor Charles Fried, who served as solicitor general of the United States from 1985 to 1989, disagrees. “I think the fuss about the shadow docket lacks perspective,” he says. Fried notes that while the Supreme Court’s emergency orders prompt headlines in “big ticket cases,” lower courts make thousands of emergency decisions annually as well, many of which have widespread ramifications, with significantly less fanfare. For instance, Fried explains, in July 2020, the 11th Circuit issued an emergency stay of a Florida district court opinion in a case that essentially disenfranchised approximately 800,000 ex-felons before the 2020 presidential election. The district court decision would have allowed the ex-felons to vote without first paying off all court costs, fines, and fees, a requirement added by the state legislature after Florida voters overwhelmingly voted to allow former felons to vote once they completed their sentences.

I think the fuss about the shadow docket lacks perspective.

-Charles Fried

Fried emphasizes that the Court’s emergency orders are not “decisions,” because the Court makes only procedural rulings rather than binding precedent on the shadow docket. But procedural decisions can have far-reaching substantive consequences, as in the Texas matter, where Fried acknowledges that “there’s going to be a lengthy interval during which women seeking abortions in Texas won’t be able to get them.”

Likewise, Steiker notes, procedural decisions in death penalty cases can bring abrupt endings to appeals that then never see the light of day on a merits docket. “Non-merits decisions, like lifting the stay on an execution, allow executions to go forward just as surely as if the Court had denied the petitions on the merits,” Steiker says. “They take effect as if the Court were deciding on the merits, but the Court doesn’t have to reason them out and doesn’t have to make law. They can just let things happen.”

The result, Steiker says, is often greater obfuscation by the very body trusted to make law that will bind federal and state courts nationwide. “A lot of the things we think of as associated with rule of law values—consistency, accountability, deliberation, transparency, opportunity to be heard fully—don’t happen in the shadow docket, and that’s true regardless of the substantive area of law at issue,” Steiker says.

In response to increasing public scrutiny, Congress in February held its first-ever hearing devoted to the shadow docket. Lawmakers considered possible legislation to increase the Court’s transparency, such as requiring justices to disclose their votes on divided emergency orders. Steiker believes it is unlikely, however, that monitoring the shadow docket will become a congressional priority in an era plagued with life-and-death concerns such as the pandemic, climate change, and criminal justice reforms. “This administration has a lot on its plate,” says Steiker. “Not everything will get done.”