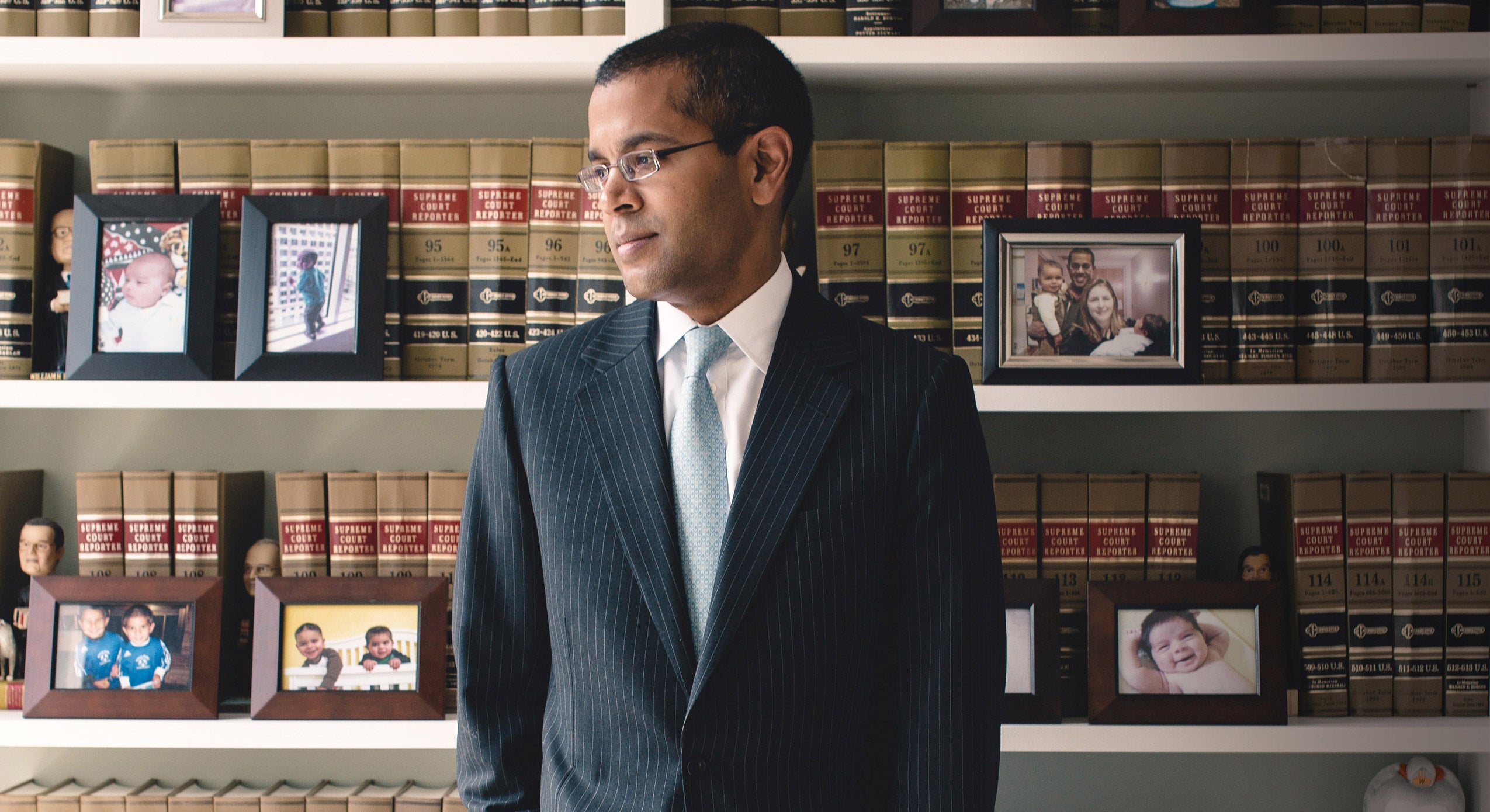

Many lawyers dream of the day that they can stand in front of the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court and argue a case. For Kannon Shanmugam ’98, a partner at Washington, D.C., litigation powerhouse Williams & Connolly, that milestone came just six years out of law school, after he clerked for Justice Antonin Scalia ’60 and joined the U.S. solicitor general’s office. It has now been followed by 16 other arguments, three of them in the 2014-2015 term. This spring, he spoke with a Bulletin reporter about the challenges and exhilaration of Supreme Court advocacy

Was appellate law a path you planned to pursue since your first day of law school?

It was only after clerking and spending some time in private practice that I really decided to focus on appellate work. If you had told me when I was in law school that one day I’d wake up and have argued a number of cases in front of the Supreme Court, I would have said you were crazy.

You had your first argument before the Supreme Court when you were just 31 years old. What was it like to be so young and in that position

I was too young to realize just how scared I probably should have been. It’s a great privilege to have that opportunity, and one of the reasons is that there have been so many great advocates at that bar. The first Supreme Court argument I ever saw was by now Chief Justice Roberts (’79), and I remember thinking, There’s no way I could possibly do that, because he was just so good

What do you mean by “good”? What makes an appellate advocate effective?

The best Supreme Court advocates are the ones who have just an overwhelming command of the law and the facts and who are able to answer the hardest questions in a way that advances the client’s cause. That is a rare skill: the ability to persuade a court in cases where, almost by definition, there are good arguments on both sides. The best arguments are by those who are able to acknowledge that there are weaknesses in their positions, but show that their preferred outcome is the right one.

How do you prepare for oral argument?

There’s no substitute for the work that goes into preparing for oral argument. It involves reading the briefs multiple times and reading everything that is cited in the briefs, but also spending a lot of time just thinking through the contours of my client’s position and undergoing moot courts where people simulate the experience of the oral argument and ask the hardest possible questions. It is a demanding process, and often it’s less than the most enjoyable part of the process, but it’s essential in the Supreme Court because it is such a smart court. If there is any weakness in the position, it will be exposed at oral argument, and you have to be prepared to deal with that and address any weaknesses you can.

What’s the difference between working on an appellate brief as a writer and being the person at the lectern at oral argument?

Oral argument is the time that the Court gets to ask the questions that don’t get answered in the briefing. It’s the one opportunity justices or judges have to pin down questions that parties may not have been willing to volunteer answers to in their briefs. It forces the parties to answer the very hardest questions for their side. Sometimes it’s really only at oral argument that you see the parties come together on an issue.

What was the most memorable case you worked on?

Maryland v. King, which was about the constitutionality of collecting DNA from arrestees. There was a moment during oral argument when Justice Alito said he thought it might be the most important criminal procedure case the Court had heard in decades, and that was an electric moment. The case was very close, as it turned out, and unfortunately, we were on the losing end. It still was a great professional experience to work on a case like that, even if you’re disappointed by the result.