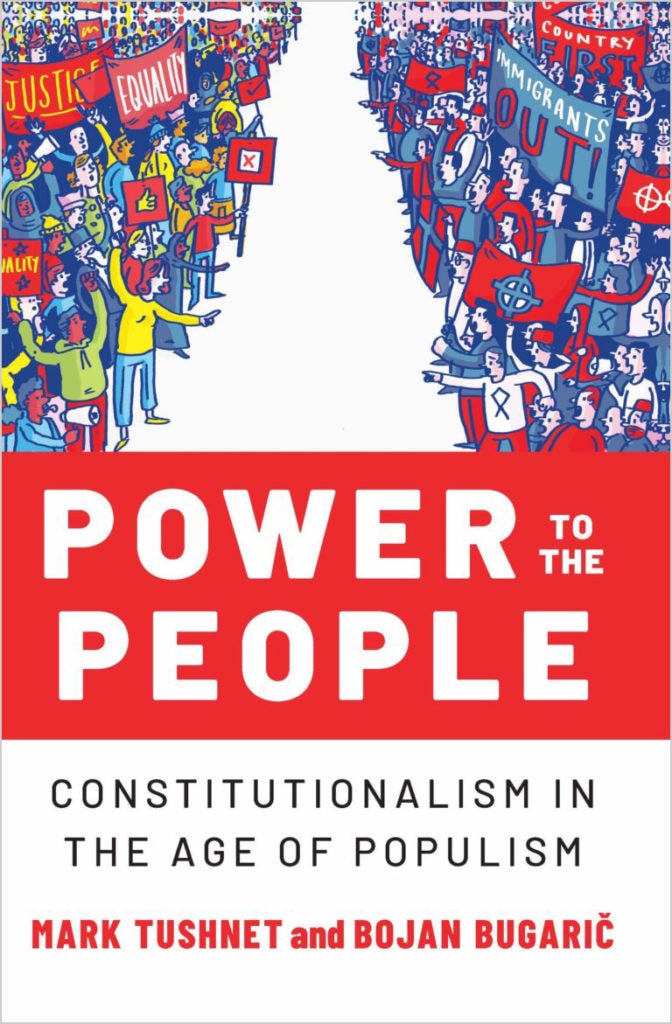

Despite the seemingly endless examples of right-leaning populist authoritarian leaders and aspirants at home and abroad, populism is neither inherently conservative nor necessarily inconsistent with constitutional democracy. That is the central theme of a new book, “Power to the People: Constitutionalism in the Age of Populism,” by Harvard Law Professor Emeritus Mark Tushnet and Bojan Bugarič, a professor of law at the University of Sheffield. While praising the volume as “important,” “a necessary corrective,” and “an absolutely terrific, terrific book that deserves to be read and discussed,” three fellow scholars at a recent online panel sponsored by the Harvard Law Library raised a series of questions that they said could bear further examination.

Opening the program, Bugarič said he and Tushnet had intentionally set out “to challenge the mainstream, the dominant view, that populism is always in every instance antithetical, inimical, incompatible with constitutionalism.” To do this, they examined a series of case studies of populism across the globe and tried to draw empirical conclusions. While they found instances of “populists dressed up as autocrats,” who violate constitutional norms, the authors also came to believe that “sometimes populism is a needed corrective to anti-democratic tendencies in current politics around the world.”

Responding to the book, University of Chicago Law School Professor Tom Ginsburg said that, while he is convinced that populism “in some forms can be pluralistic,” he nevertheless remained “a little skeptical of most populism.” The problem, he said, is that most populists aren’t grounded in the institutions and technocratic bureaucracy that makes democracy work.

“One of the things that I think we observe with lots and lots of populist movements…,” Ginsburg observed, “is a desire to shrink that space, that is to actually undermine the institutions” that underpin democracy. He also noted, however, that the book showed that not all people who run as populists end up governing that way.

Harvard Law School Professor Lawrence Lessig argued that any analysis of populism should not ignore the question of how voters access information about the issues they are asked to decide at the polls. He took particular aim at social media, which he said exists to “drive people into partisan corners.”

“This is not a bug,” Lessig argued. “This is a feature of a system because the more they can enrage us and polarize us, the more profit they make.” In response, we need, he said, “to be realists about how the people are engaged, or how they understand what they are engaging with, so that we can guide … the process in a way that brings out the best of them when they are playing their role.”

He also questioned one of the central elements of constitutionalism the authors lay out in the book, the idea that policies must be determined by the preferences of the popular majority, and whether it aligns with the reality that the U.S. is in many ways ruled, he said, by a minority of the people. Lessig argued that democracy in the United States is more minoritarian than majoritarian due to several factors, including gerrymandering, which helps determine the compositions of state legislatures and the House of Representatives; population imbalances among the states that are reflected in the Electoral College and the U.S. Senate; and the Senate filibuster, which he says means many decisions in that body are controlled by “21 states representing 21% of America’s population.”

“So, I just wonder whether, in the context of thinking about what a constitution is, there isn’t more work to be done about the relationship between constitutionalism, the liberal constitutionalism you’re describing, and majoritarianism as an essential qualification for it,” he said.

A self-described critic of the U.S. Constitution and proponent of a new constitutional convention, Sanford Levinson, a professor of law at the University of Texas Law School and a visiting professor at Harvard, mused about whether his stance makes him a populist.

“If one really defines populism as being anti-institutional, then I suppose the answer has to be ‘kind of,’” he said. “And I’m certainly hostile to those political elites who either praise the Constitution or simply say, we shouldn’t worry about the Constitution so much, because other things are so much more important that the Constitution basically becomes nugatory. So, this depends obviously on how one defines populism.”

Levinson praised the book for distinguishing between nationalism and popular sovereignty. All nationalism, he said, is “basically dangerous” because it is based on the idea of shared national characteristics. By contrast, he explained that popular sovereignty “focuses on the fact that a lot of people are occupying a given territory, and they are not united by national characteristics.”

“People who live within a certain territory ought to be allowed to engage in self-determination,” Levinson said. “And I think … one of the most valuable contributions in the book is to say that you can be a populist and a pluralist at the same time.”

But like Lessig, Levinson also questioned the validity of one of the elements that the authors say are necessary for constitutionalism, in his case, judicial independence. Every form of judicial selection is flawed, he argued, regardless of whether it is a matter of “genuine institutional self-perpetuation” in which judges pick their own successors, as in India, or the “thoroughly politicized” process in which the U.S. president “and a compliant party in the Senate,” appoint people to the bench, or the Texas system of popularly electing judges. These issues, he said, combined with others, such as whether there should be judicial term limits, have prompted other scholars to ask whether the idea of judicial independence should be retired.

“I think that the book ought to inspire more discussions of what one means by judicial independence, rather than simply to use it as a mantra to castigate certain … presumably populist movements,” he said.

At the end of the 45-minute program, Tushnet responded to a few of the panelists’ comments and questions, beginning with Lessig’s observations about anti-majoritarianism.

“A very large number of the populist mobilizations occur because the structures in place manifestly, or at least are claimed by populist movement leaders to manifestly not represent either the views or interests of the nation’s people,” Tushnet said. “And, so, these movements are motivated by a concern about re-establishing … majoritarian control.”

Populists often see themselves, he explained, as overcoming institutional barriers that in their view have stymied the implementation of the popular will, from the technocratic bureaucracy Ginsburg mentioned to the independent judiciary that Levinson questioned.

The people, who “want to get stuff done,” sometimes challenge the constitutional institutions — or “veto gates” — that are standing in their way. “Whether that’s good or bad thing will depend on a combination of the nature of … the institution they’re challenging and the merits of the program.”

“None of this is to say that every particular attack on existing institutions is justifiable,” Tushnet said. “We think that the better way to think about these questions is not to focus on the fact that the institutions are being challenged, but on the motivation, the nature of the challengers’ overall political agenda.”

The event was one of a year-long series of talks sponsored by the Harvard Law School Library focusing on books authored by faculty members. The next in the series will occur Thursday, October 14, and will focus on “Say It Loud!: On Race, Law, History, and Culture,” by Professor Randall Kennedy.