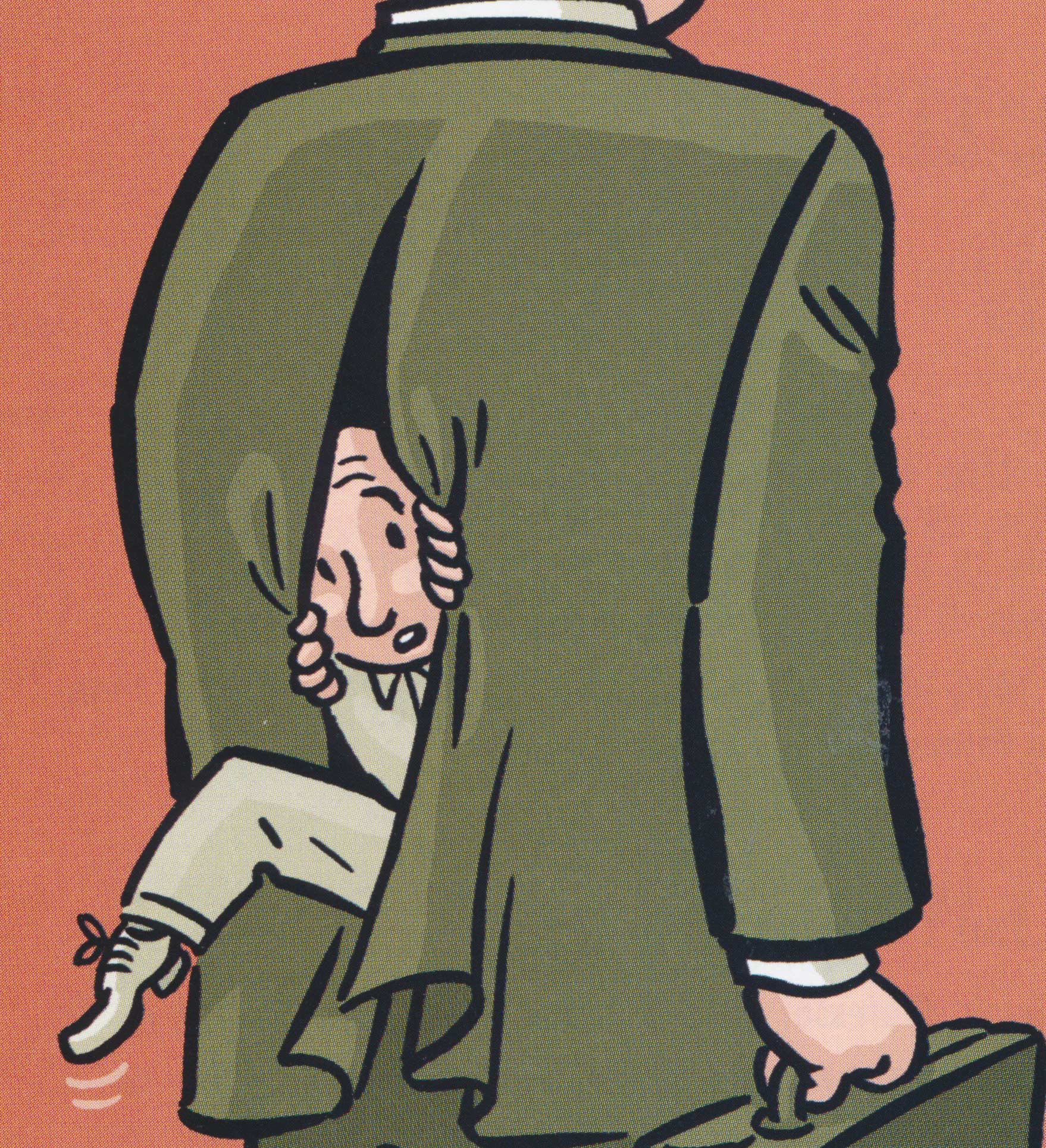

Robert Kurson must have been lying. Surely, thought his prospective employer, no authentic graduate of Harvard Law School would want a menial, entry-level job.

Robert Kurson set out to prove him wrong. Not only by confirming that he did indeed graduate from HLS. Not only by accepting the job, a data-entry position in the sports department of the Chicago Sun Times. Not only by climbing the ranks to become a senior writer at the newspaper. Ten years after earning his degree, Kurson ’90 set out to show the world, through his own story and the story of several classmates, that HLS graduates do not always follow a predictable path to success. Even if the world—and the graduates themselves—expect nothing less.

Currently a writer for Chicago Magazine, Kurson explores “what happened to the souls of the class of ’90” in the August issue of Esquire magazine. Titled “Who’s Killing the Great Lawyers of Harvard?” his story exposes a class that has in large number fled the law, whose hopes from the “days when we were golden” have been tarnished and battered, and whose struggles belie the mythology of omnipotence surrounding the HLS graduate.

“When I was admitted to Harvard Law School, I believed that all my worries were over for the rest of time,” said Kurson. “It didn’t turn out to be true for me, although the degree has helped me, and it didn’t turn out to be true for some others as well.”

Those others include four classmates profiled for the story: Victor Bernace, who became a teacher at the tough, inner-city high school he had attended and later defended taxi drivers in traffic court; Chris Crain, the campus conservative who came out as a gay man and quit a law firm to buy several gay newspapers; Greg Giraldo, who also quit a large firm to break into stand-up comedy; and Andrea Kramer, a passionate civil rights advocate whose need to support a family hampered her dreams of changing the world.

They are not alone in their doubts about practicing law and about their rightful place in the professional world, Kurson says. Yet not a single graduate who is dissatisfied with work in a law firm would talk to him for attribution. They are risk-averse people, Kurson asserts, who worked hard, studied hard, and will not hazard the chance that they will be recognized, even in anonymity.

Some people who work in firms did speak to Kurson for attribution, however. He quotes members of the Class of 1950, satisfied with their lives and work. And he quotes fellow Class of ’90 graduates who don’t understand the angst, the shock that the world can be tough, even for HLS graduates. “Harvard Law students are whiners,” one said. “They’re removed from reality.”

Perhaps, Kurson says, many readers of the article will agree. But he knows that the HLS name had been built up to him for as long as he can remember. An HLS degree, everyone says, opens the door to myriad opportunities (and, says Kurson, everyone is right about that). Yet people who gain admittance to HLS don’t often consider the logical extension of a law degree. “Very few people raise the idea of how happy you will be doing legal work, what’s required of a big-firm attorney,” said Kurson. “These are the realities you face once you get in and especially once you get out.”

In some ways, the School breeds graduates who are discontented with the legal world because of the very quality that makes HLS the preeminent law school in the world, according to Kurson. The institution’s greatest asset, he says, is its admittance of the most accomplished yet eclectic applicants.

“If you take a collection of those people and put them in a profession where some of the top requirements are your ability to be organized, your ability to keep track of deadlines, your ability to understand rules, you may have a big conflict on your hands precisely because you’ve recruited the most interesting people,” said Kurson.

Speaking shortly after the publication of the story, Kurson said he already has heard from many people who believe he has captured a fundamental truth not only about HLS graduates and the law, but about the value—and burden—of work in society.

“It seems to have resonated not only with Harvard lawyers but to lawyers in general and most importantly to professionals in general,” Kurson said. “The most gratifying feedback is from non-lawyers who say they related completely to the stories in my piece. It’s just representing issues in the world of American work.”