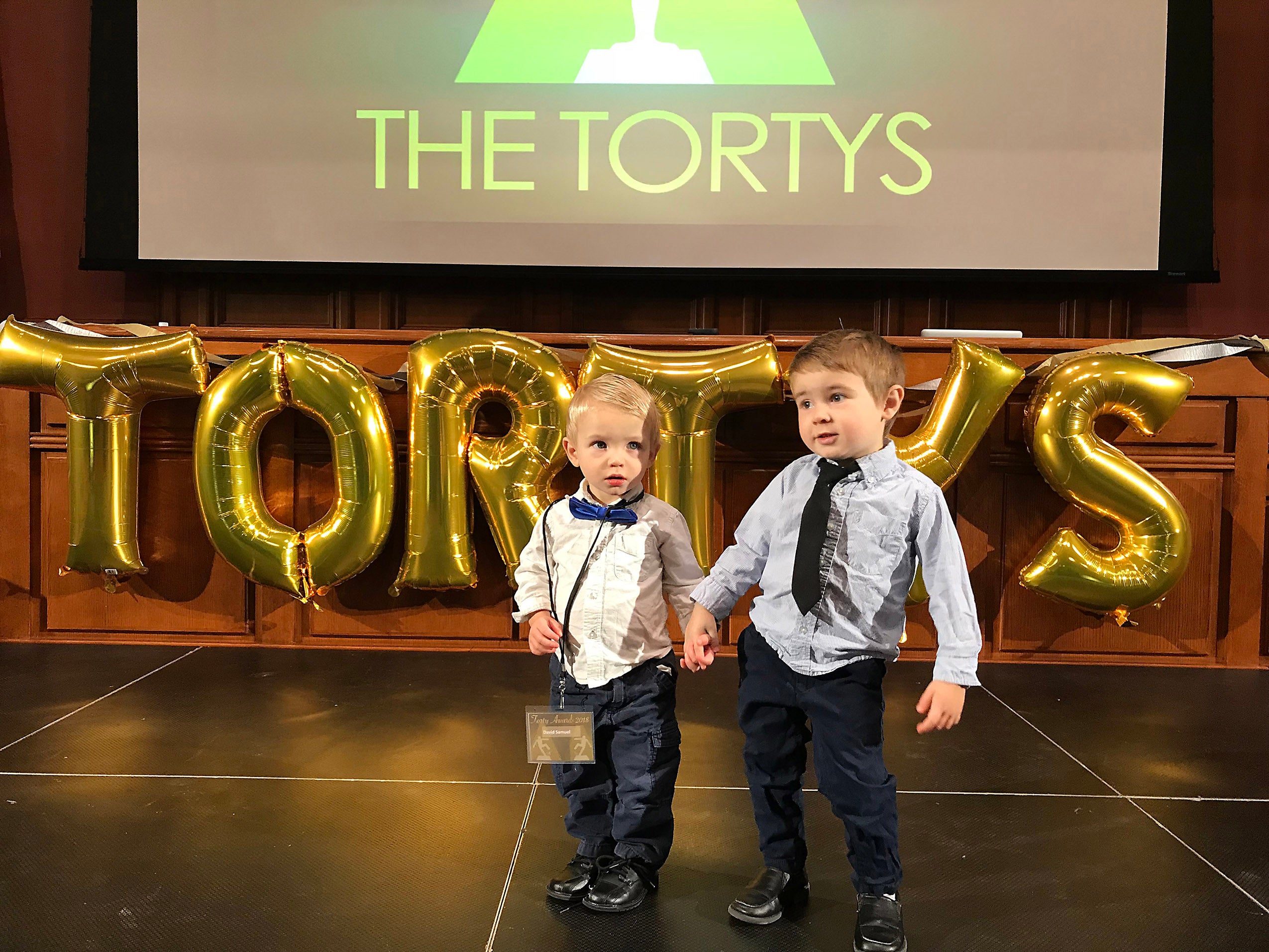

It was Thursday night and the Ames Courtroom was decked out for a Hollywood-style awards ceremony, with live music, dancers and comedians. 1Ls and their dates arrived in tuxes and ball gowns while a jazz combo played, and anticipation was in the air. The winter’s first snow was falling outside, but in Austin Hall, the Tortys had come to town.

Professor Jon Hanson, a three-time winner of HLS’s Sacks-Freund Award for Teaching Excellence, conceived the Oscar-style ceremony last year as a tongue-in-cheek way to showcase research videos made by Section Six students in his 1L torts class. It’s since grown into one of the first semester’s leading social events–and a chance for students to display their talents, ranging from comic monologues to an a cappella vocal group, to a full hip-hop dance number between the screenings. Elisabeth Mabus ’19, returned to direct the ceremony, which was hosted by Emily Mannheimer ’19 and James Pollack JD/MPP ’20.

“One of the goals is to give students a chance to connect with things they loved to do before law school,” Hanson said shortly after the ceremony. “It’s a reminder that they are multi-dimensional people–that they have amazing talents that don’t always come through in the classroom. There are older students who come back as performers and audience members or as members of the Academy [which votes on the videos]. Part of the event is about creating some levity and play, but it is also about engaging difficult topics together as a community.”

Hanson credits his teaching team–Jonathan Eubank, a 3L; Molly Broderick and Oladeji Tiamiyu, both 2Ls, and Jacob Lipton ’14, co-director of the Systemic Justice Project–for their work on designing and administering the Tort Reports project, under whose banner the videos were created.

Despite the festive nature of the event, the videos themselves were investigative and at times sobering. One of the winning entries, “Outsourcing Infection: Guatemala Syphilis Experiments 1946-48,” documented a little known episode in American medical research, when a medical research team in Guatemala City infected 1,500 of the indigenous population with venereal diseases; 83 of the test subjects died. Vulnerable populations of prisoners and mental patients were targeted, with the consent of both the U.S. and Guatemalan governments. According to the video, the U.S. in fact put pressure on the Guatemalan government to agree to the experiments. The video includes footage, borrowed from a previous documentary, of a female survivor who recalls being forcibly infected by the researchers as a ten-year-old.

“We made the aesthetic choice to include that human element in our video,” says Antonio Linares, who was part of the student team who created it. The team selected the topic from a long list of social problems that students had nominated, and wound up tracking down one of the attorneys who represented the plaintiffs in a 2011 lawsuit. “We actually found a Guatemalan website that asked people connected with the experiments to contact his firm,” Linares said.

Fellow team member Kayla Blaker ’21 adds that Hanson gave them the freedom to choose the direction of their video. “All of us became very attached to the topic, so it added a personal element that we don’t necessarily see in our other classes. When you study cases in law school, you read about how point A gets to point B but you don’t always see the context and the consequences of what’s happening. So this video really put into context the questions of sovereign immunity, and immunity from responsibility. We wanted viewers at the Tortys to see the weight of the issue, how it impacted the victims and their families.”

According to Hanson, researching such issues—particularly one like the Guatemalan experiments, where there wasn’t a happy ending—can be especially valuable. “The project gives students an opportunity to grapple in the first semester with the challenges of learning about, discussing, and debating the sort of injustices that motivated many of them to come to law school. In the process, students often discover the limits of the law.” By focusing on a policy problem, Hanson explains, “students come to understand how the underlying laws can be part of the problem. The video on Guatemalan experiments, for instance, addressed a horrendous practice for which the law provided no remedy. For some students, the deeper lesson may be that, to promote meaningful change as lawyers, they shouldn’t just be learning what the law is or even how to advance justice through those laws; they also need to consider how laws themselves may have to change to make our system more just.”

In all, the class produced sixteen of the eight-minute videos, of which five were awarded Tortys by the 200-member “academy,” consisting mainly of former Section Six students. Other winning entries examined the Alien Tort Statute and its relation to human rights; changing legal attitudes toward use of personal data; and a proposed app that legally registers consent for a sexual encounter. All of this and last year’s entries can be seen on a YouTube channel known as TortyTube. “We’re creating an archive for our future students to learn from,” Hanson says. “I’ve used some of them in my own teaching, and I’ve been contacted by lawyers who are interested in those topics.”

This year’s most coveted prize, the Grand Torty, went to “The Impact of Race on Tort Damages.” This too addressed a glaring legal problem, that members of racial minorities often receive substantially less in damage awards due to the presumption that they have less earning power. According to author Martha Chamallas (co-author of “The Measure of Injury”) who was interviewed for the video, race-based tables even tend to predict that African-American men will earn less money because they are likely to be incarcerated. “Capturing systemic problems is challenging to do in a brief video,” Hanson explains, “but they pulled it off by focusing on a particular element of the problem, employing accessible graphics, and incorporating clarifying interview clips from a world-class scholar.”

According to Genevieve Antono, part of the winning team, making the video led her to think more about laws in context. “That’s one thing Professor Hanson’s class is really good at—not just looking at the black-letter law, but really questioning the institutional structures that are behind the law and whether they are fair and just.” She also valued the experience of putting the video together in a team, making use of individual skills. “We had such a perfect balance of talents: There was a natural leader, a creative genius, an incredible narrator, a practical do-er… and me. I spent the entire project looking at my teammates and thinking, ‘Wow, I want to hire you.’”

The team effort, she said, also made the Tortys memorable. “It was a huge black-tie celebration, ridiculous and wonderful. It makes being a 1L a lot more enjoyable and human.”