LL.M. students recall their work in Afghanistan and share their hopes for the nation’s future

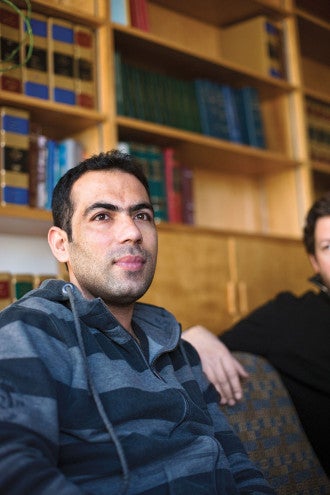

Sitting in a graduate student lounge at Harvard Law School, Sayed Mohammad Saeeq Shajjan can look to his left and look to his right and see hope for his homeland of Afghanistan. He is flanked by Rebecca Gang and Andru Wall, fellow LL.M. students who, along with Shajjan, have worked to stabilize and strengthen a country racked by war over three decades. They came to the LL.M. program after spending time in Afghanistan in different roles, together representing a confluence of efforts needed for the rule of law to predominate in his country, says Shajjan.

“The work that we have all been doing in Afghanistan is very important,” he says. “As an Afghan, I really appreciate that they put their lives at risk in coming and helping us. And I’m looking forward to them coming back there.”

Though now far away, Afghanistan is still very much in their thoughts, which they share with the Bulletin not long after U.S. and Afghan troops have mounted a major military offensive in the country. Before he left the U.S. Navy JAG Corps, Wall was enmeshed in such action as a senior lawyer for U.S. Special Operations Command Central, a responsibility that took him to Afghanistan often between 2007 and 2009. In that role, he focused on the issue of civilian casualties and on supporting and incorporating the rule of law. Gang—also an American—worked in the country as a consultant for the Norwegian Refugee Council on civil law issues and later helped establish Afghanistan’s first independent bar association in 2008. While she was working on that project, she met Shajjan, an attorney affiliated with the International Development Law Organization who had been selected to help create Afghanistan’s first Independent National Legal Training Center in Kabul, a central institution in the national vision to build the country’s legal capacity.

“The situation [in Afghanistan] is very different now. Even judges are calling defense attorneys saying, We will have a trial tomorrow; we would like to see you.” —Sayed Mohammad Saeeq Shajjan

The three students share an easy rapport, despite their disparate backgrounds and experiences. Those different perspectives are all needed in a place like Afghanistan, they say. Establishing the rule of law requires both capacity-building and security, as well as the efforts of the national and international communities working together toward a common goal.

Wall, for example, notes that NGOs provided a valuable perspective when they, concurrent with the military, investigated allegations that civilians were killed during military operations. “We all want the same thing for Afghanistan,” he says. “Yes, sometimes we come at it from slightly different perspectives, but in reality when you sit down and talk, you realize that you have a lot to learn from each other.”

“Once you get into that environment,” Gang adds, “it’s clear that there’s not a distinct, dualist separation anymore between the military and humanitarians, which makes it complicated and murky but also teaches you a lot about dealing with each other. There’s so much crossover and so much working together.”

They know that much has yet to be done in order to stabilize the nation. And they acknowledge struggles and frustrations. Yet they also point to signs of progress. After the Soviet invasion, Shajjan moved back and forth to Pakistan with his family before returning to his homeland in 2002 and graduating from Kabul University the year after. He says that during the Soviet occupation and under the Taliban, people didn’t have a right to speak when they were arrested or learn the charges against them. As recently as 2004, he went to court in order to defend someone accused of a crime. He recalls being told that a defense was not needed—only the prosecution.

“There’s not a distinct, dualist separation anymore between the military and humanitarians.” —Rebecca Gang

“The situation is really different now,” he says. “Even judges are calling defense attorneys now saying, We will have a trial tomorrow; we would like to see you.”

Gang points to the achievement of establishing the Afghan Independent Bar Association, which has registered almost 700 defense attorneys. At first, neither the organization nor its members fully grasped its function or purpose, she says, but within a year it was playing a prominent role, including advocating on behalf of Guantánamo detainees and a member attorney who the organization believed had been unlawfully detained. The bar association’s advocacy led to the attorney’s release, says Gang.

Wall cites “great relationships” between U.S. military personnel and Afghan forces. He notes that the recent campaign in Helmand Province was directed by the Afghan government. “We’re there to help the Afghan people bring security to their country,” he says. “So we’re not going to dictate how we think things need to be done. That’s not a recipe for success.” Afghans want the help of the international security forces, says Shajjan, “because we understand that we do not have the army and police to protect the population of the country.”

The students all express optimism that progress will continue, though Shajjan cautions patience. It will take time to build something that has been destroyed over the course of 30 years, he says. But he is encouraged that more young Afghans are going to university and traveling to other parts of the world. So is Gang, as she describes a scene of little girls in matching uniforms rushing to school in Kabul every morning.

“We’re there to help the Afghan people bring security to their country. So we’re not going to dictate how it’s done.” —Andru Wall

“As people become more and more educated and more open to the outside world, there is a critical mass of idealistic, open-minded Afghans who want change, who don’t want to be seen as this hotbed of fundamentalism, who want to be part of an international community,” she says.

Gang says she feels obligated to return to Afghanistan. She doesn’t know in what role, but she wants it to be one in which she can build relationships with Afghans because that is the best way to get the job done, she says. Shajjan certainly will return home after his HLS studies. He also isn’t sure in what capacity but wants to be useful and make a difference. As for Wall, his military service is over, but he too thinks about a time when he will return to Afghanistan, not as a professional but as a tourist. He hopes for the day when he will be able to bring his children there, to show them a secure country in the process of rebirth, and to tell them that he, in a small way, helped make it possible.