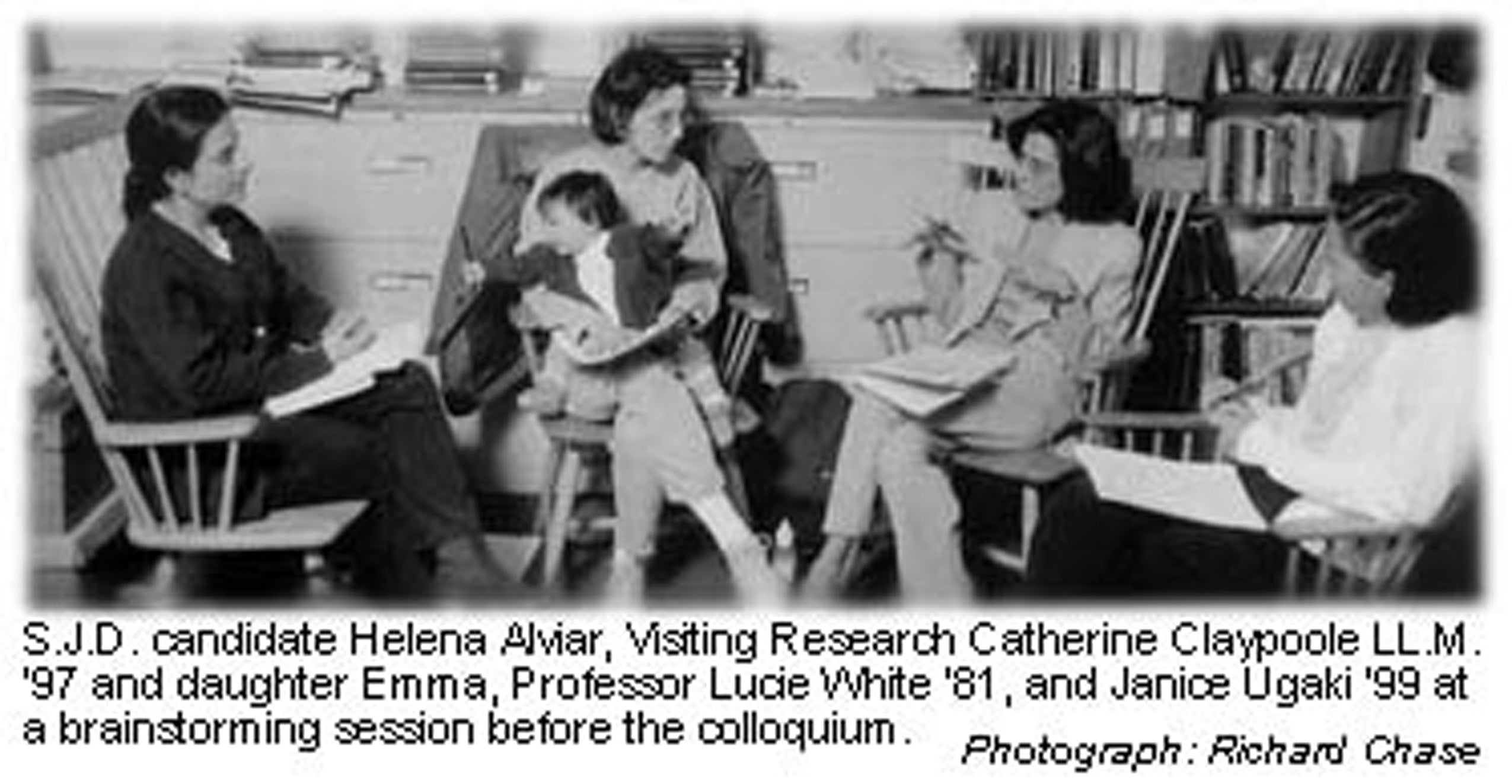

Professor Lucie White’s spring seminar Child Care, Development, Policy, and Women’s Work: Comparative Perspectives culminated in a late-April colloquium that brought together scholars, activists, and students for discussion of emerging issues involving women’s employment, social justice movements, and state policy regarding the unpaid or undercompensated care-taking —especially of young children—that women typically do.

Participants discussed “how academics and practitioners can help to shape equitable policies concerning child care, elder care, and other forms of care-taking, in light of increasing social inequality and cultural diversity all over the world,” says White ’81. Colloquium guest participants included MacArthur Fellow Sophia Bracy Harris, founder of an Alabama NGO that has worked for over 20 years with low-income parents and child care workers, in the United States and globally, to create democratic systems of high-quality, inclusive care; and Mona Harrington ’60, author of the forthcoming Care and Equality (Knopf, August 1999), as well as Women Lawyers: Rewriting the Rules (Knopf, 1993) about women HLS graduates.

The colloquium reflects White’s ongoing commitment to focusing more attention at the Law School on the law and policy of “caregiving and care-taking. Good care policy needs to be shaped in light of economic development priorities, labor standards, family policy, child development research, gender studies, and human rights norms,” says White. “Then the policy vision needs to be translated into intricate—and workable—systems of legal rules. This kind of work calls for lawyers with vision, interdisciplinary grounding, expert technical skills, and a fluid sense of what’s possible in law design. HLS should be a global center for research and teaching in this critical policy domain.”

White has written widely on the subject of child care for low-income families, emphasizing that high quality care costs far more than low-income families—especially those headed by single women—can afford, that the supply is particularly limited for unsubsidized working-poor families, and that few good options are available for any parent, regardless of income, who works long or irregular hours. She is coeditor, with Professor Joel Handler ’57 of the UCLA Law School, of the recently published Hard Labor: Women and Work in the Post-Welfare Era (M. E. Sharpe, 1999).

White’s child care seminars have included a clinical component—funded with seed money from the Dean’s Office and the Children’s Studiesat Harvard program—through which students have worked with local government agencies and nonprofits focused on increasing the supply of quality child care here in Boston, particularly for low-income women entering full-time waged work. Students in this spring’s seminar, which compared child care policies in developed and developing nations, conducted individual research on subjects including the U.S.’s and Japan’s family and medical leave policies, new policies concerning children in Venezuela and Paraguay, and employer-provided day care in the United States and India.

While White may be the first to do such extensive work on child care law at a U.S. law school, faculty at Yale, Cornell, and Columbia Law Schools are working on related issues. She is developing an interdisciplinary network of academics who share these interests.