HLS Recording Artists Project focuses on the legal side of the music industry

Musician Kabir Sen has self-produced two albums, performed widely in the Boston area with other hip-hop artists, even appeared on the cover of Billboard magazine. But he felt he’d missed a beat when it came to contracts, business plans and the laws that govern his industry. So Sen, like dozens of other Boston-area musicians and producers every year, turned to HLS’s Recording Artists Project.

It started in 1998 when two students approached Hale and Dorr Legal Services Center instructor Brian Price about a clinical focused on music and the law. “Their interest sprouted mostly from the desire to empower musicians,” said Price, who has a background in music law and heads the Community Enterprise Project, the clinic’s transactional practice. “The entertainment industry is notorious for being unforgiving if you don’t know what you’re doing.”

Initially, the project focused on hip-hop and R&B artists. Clients now include a wider array of musicians as well as small production and management companies. The program has also grown beyond its clinical function: RAP now hosts panel discussions–this spring on alternative revenue streams in the music industry–as well as social events. It also launched a Web site this year with the Berkman Center for Internet & Society (www.cyber.law.harvard.edu/rap), which provides practical information on legal issues for those navigating the music industry.

For 3L Marina Bonanni, who has been a member since her first semester and co-director for the past two years, RAP has been an essential part of her law school experience. “It brings together students who love music and are dedicated to entertainment law,” she said. As for the clinicals, “You have clients who are really excited, really passionate about their music, and you’re just helping them make their dreams come true.”

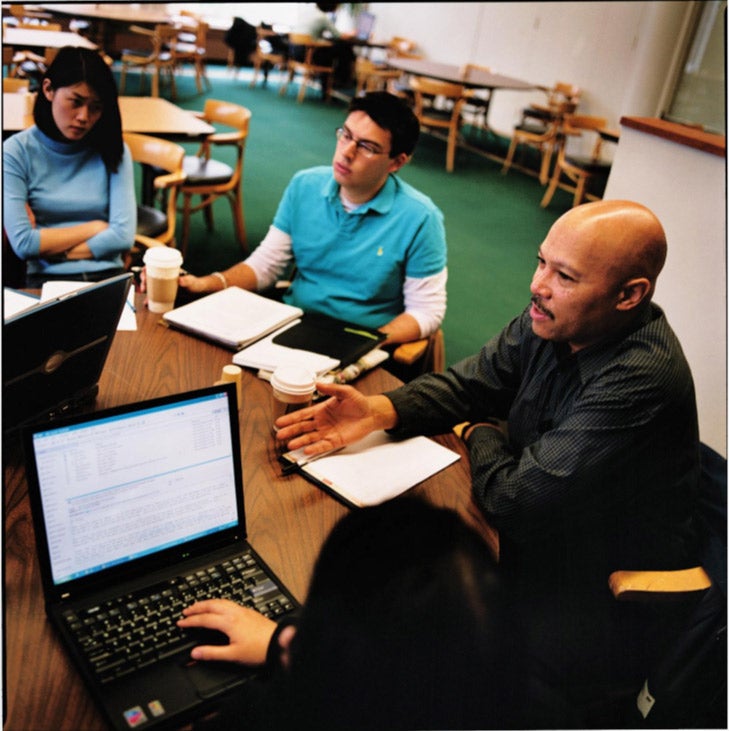

In February, when Kabir Sen met with Price and a team of RAP students at the Hale and Dorr Center, he clearly had lots of dreams for his music–and lots of questions. The team was prepared. One student asked about forming contracts with the other musicians Sen works with. Another explained the protection offered by forming a limited liability company. Another talked to him about the relatively small fee and large protection involved in trademarking his name. Another suggested that he register his songs with organizations such as the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, which collects royalties.

They also listened to Sen’s concerns about copyright problems relevant to many hip-hop artists. The musician explained that, although he performs with a band, he also creates his own electronic music, which includes samples of pre-existing works. “Sometimes I feel like I know there is just the right sample out there,” he said, “exactly what I need to make that song sound incredible.” What he needs to know, he says, is what the law allows.

That’s where RAP comes in. And the answers often end up being relevant to RAP students’ own careers. Paul Petrick got involved in the program last year and is now on the board. He’s a 3L but he’s also a deejay, and he is starting his own record label called Headtunes, featuring electronic music. By the time he signed his first two artists this year, he–like other RAP students–knew how to draft recording and management contracts and booking agent and band agreements. He could also set up his own LLC and was versed in publishing and performance rights, copyright and trademark issues. “From a practical standpoint, it was great,” said Petrick. “Everything I learned for what I’m doing now, I learned there.”