Most law school graduates look forward to seeing their mothers and favorite professors at their commencement ceremonies. Very few see their 4th grade teachers or the mothers of their professors cheering them on as they receive their diplomas.

Michael Donohue, who graduated from Harvard Law School Thursday, is the exception. When he first set foot in Professor Andrew Manuel Crespo’s ’08 criminal law class as a first-year student three years ago, little did Donohue know that Crespo was the son of one of his most inspiring elementary school teachers, Sandra Correa.

Today, after he received his diploma, Donohue and Correa were reunited for the first time in nearly two decades. Although she’s already attended two Harvard Commencements, when her son Andrew graduated from the College and the Law School, Correa says her third will be particularly special.

“To return now, and to see Andrew not as the graduating student, but as the professor, who taught one of my own former students, well, I’m just overcome with happiness and joy to be able to experience this,” she said. “When Andrew started teaching at Harvard, I told him that we would be like bookends — that I would teach them at the beginning of their education, and that he would teach them at the end. But I never imagined we’d actually share a student.”

The “Michael Donohue Scale”

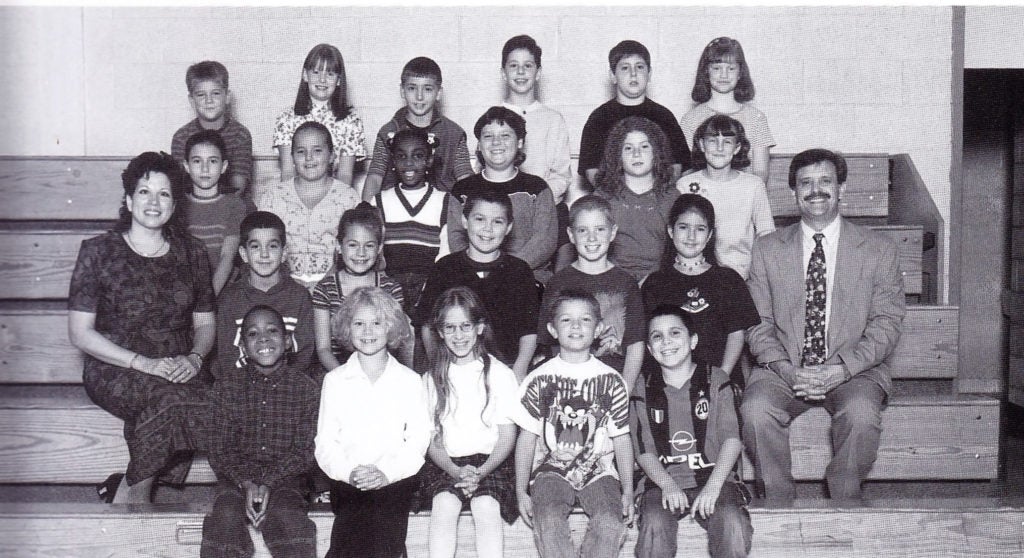

“Michael was easily one of the most intelligent students I’ve taught in my 38 years as a public school teacher,” Correa said. “He finished every test before everyone else in the class, and got a perfect score every time. I started using his answers as the key to grade the other assignments.”

“And yet, while I suspect he may have known then just how smart he was, he never acted like it,” she recalled. “He was a quiet, kind, and humble little boy who never once acted as if he was smarter or better than anyone else in the class. That was what I loved about him the most.”

Correa remembers being struck by the young Donohue’s “thoughtful and mature, almost adult-like” comments on current events in Social Studies class. And he was such an avid reader that she often lent him books that her sons — including his future law professor — had read at the same age.

“I remember reading and discussing those books with Andrew,” she said, “and then discussing them years later with Michael as he wrote reports for me about each one.”

Donohue was such a star that he was known to Correa’s family as the student by which all others were measured.

According to Crespo, “Well over a decade after Michael had moved on from her classroom, my mother’s colleagues would jokingly still ask her, when inquiring about some other gifted youngster, ‘But, where do they fall on the Michael Donohue scale?’”

In fact, Correa only gave up on the Michael Donohue scale six years ago when she started teaching younger students in second grade because, she says, “At that point it didn’t seem fair.”

For his part, Donohue fondly remembers his time in Correa’s class. “She is an excellent teacher. I loved going to her class every day. She taught us with so much energy and infectious enthusiasm. My younger sister was lucky enough to have her as a teacher, as well!”

Donohue and Crespo

Early in his time at Harvard Law School, Donohue’s talent was apparent to one of his new professors, even if their shared connection wasn’t.

“I was lucky enough to teach Michael on one of his first days of law school as a 1L, and on his last day of law school as a 3L,” said Crespo, referring to the first and third years of a law school education. “He was a standout student from beginning to end. Whether in class or in office hours, he always had the most thoughtful things to say about the criminal justice system. I could tell from the start that he’ll not only be a gifted and successful lawyer, but a fair and compassionate one as well. I am certain he will do well, and I know he’ll do good.”

For his part, Donohue expressed appreciation for Crespo’s mentorship over the past three years.

“Prof. Crespo taught my very first law school class…and taught my last class in law school this spring,” he said. “Every class I attend with him is a joy, and I know I am a better lawyer for having been taught by him. He is a valued mentor, and I look forward to having him as a part of my career as I go forward.”

A path to the legal profession wasn’t foreordained for the 4th grader in Correa’s class. Asked recently if he knew then that he’d eventually be a lawyer, Donohue responded emphatically.

“No! I was going to be a physicist and invent hyperdrive,” he said. “I loved math and science as a kid.”

His memory strongly mirrors the words he penned for his 4th grade yearbook.

“When I grow up I’m going to be an astronaut and land on Mars,” Donohue wrote after giving a shout out to his teachers, including Crespo’s mother. “In the new millennium I hope to see colonies on Mars and the Moon without gravitational segregation.”

Making the Connection

Donohue grew up in upstate New York, in a village of nearly 3,000 named Florida.

“It was very much a classic small town,” Donohue said. “There was a classic main street, and I could easily ride my bike to see my friends around town…The school was right up the street from several farms that had rich black dirt. When the wind got too bad the sky would turn black and we’d be held back from recess.”

The town’s claim to fame was that it had been the birthplace of William H. Seward, Abraham Lincoln’s rival for the presidency, then secretary of state.

“Our talent show was called ‘Seward’s Follies’ in his honor and his birth home was a landmark in the center of town,” he said.

During office hours of Donohue’s first semester, Crespo casually asked Donohue where he was from. After hearing Donohue’s answer, Crespo inquired if he’d gone to Golden Hill Elementary School.

“Whose class were you in for fourth grade?” Crespo asked. While Crespo’s mother goes by Correa now, she was known to students in Donohue’s time as Mrs. Crespo.

“That’s when I put two and two together,” Donohue recalls, “realizing this Crespo was related to the Crespo that had taught me 20 years earlier. We sat in stunned silence for about 30 seconds.”

The news reverberated through Crespo’s family. When he told his brother, now a surgeon in Manhattan, that one of their mother’s former students was in his class, his brother responded. “Wow….Wait, was it Michael Donohue?’”

4th Grade Reunion at Harvard Law School

As the days towards commencement began to tick down, Crespo and his mother decided to stage a surprise reunion. Unbeknownst to Donohue, after Correa finished teaching her 2nd grade class on Wednesday, she jumped in the car and drove more than 200 miles to be on campus for Thursday’s commencement ceremonies.

Correa and Donohue had already crossed paths once during his time at Harvard Law School, but hadn’t realized it. Crespo often invites his mother to observe him teaching large classes. “It’s particularly fun to learn from her as an educator,” he said. “She always has helpful pointers!”

Correa attended Crespo’s criminal law class during Donohue’s first semester, sitting directly behind her former student.

“It was before I had realized the connection, so we didn’t recognize each other,” Donohue said. “Understandable; I have less hair on my head and more on my chin than in fourth grade.”

Thursday afternoon, as Donohue walked off the stage, diploma in hand, Crespo and Correa were there to greet him and his family and friends, including his parents, Angie and Mike. As a graduation gift, the mother and son teaching team presented Donohue with a pair of bookends, symbolizing their influence on the beginning and end of his educational path.

Correa and Donohue embraced for nearly a minute, while she congratulated him for graduating. “Thank you,” he responded. “You helped start it.”

“I’m so happy to see him, I’m shaking,” said Correa, tears still in her eyes. “He’s the same Michael, just a little taller.”

“Today was such a pleasant surprise!” Donohue said. “It was amazing to see Mrs. Crespo again after so many years. My parents were overjoyed to see her, too. Today was a strong reminder that I’m not here on my own. Rather, I’ve been supported by an amazing network of teachers, both Crespos included. I was touched that she had such a strong memory of me, and I hope to make her proud in the future.”