Starting in May 2013, in Syria’s war-torn cities of Aleppo and Idlib, specially trained operatives moved from door to door with a singular purpose. Seeking willing participants, they were armed, but only with questions.

Months of canvassing resulted in hundreds of survey respondents. After three waves of interviews along the front lines of battle, patterns of the psyche started to emerge. Gathered within a 47-page compilation of data are the collective thoughts of four demographic groups: Syrian civilians, Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters, Islamic militants, and ex-fighters.

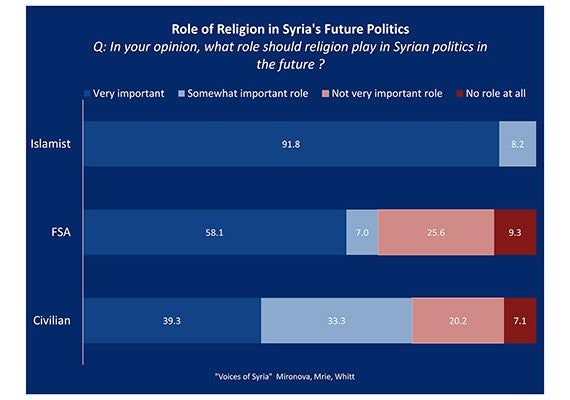

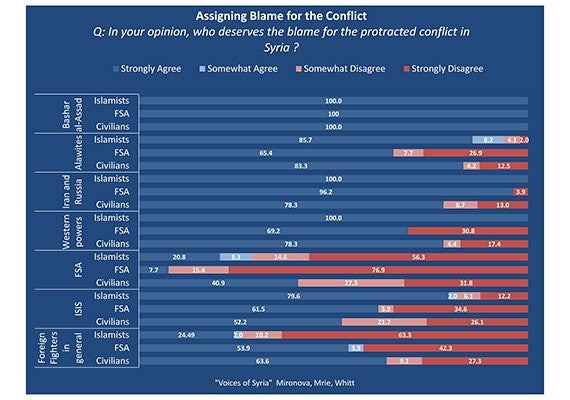

Vera Mironova, a graduate research fellow at Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation, was one of the lead authors of the “Voices of Syria” project, which covered topics such as current living situations, safety concerns, the future role of religion — among other key issues in Syria’s government. Mironova, a fifth-year year Ph.D. candidate at the University of Maryland, oversaw and coordinated the operation on the ground. Her goal: to capture the civil war in its most raw form.

In an interview with the Harvard Gazette, Mironova discussed her findings.

GAZETTE: What was your interest in the ongoing Syrian conflict and how did you get involved?

MIRONOVA: At first, when I started graduate school, I was interested in studying post-conflict environments, but I soon realized that the most understudied and intriguing part of war is what [happens] during the conflict itself. The Syrian civil war just began at that time so I decided to make the switch. I wanted to find a conflict to study before any possible intervention took place. I [was] looking to track public opinion inside the Syrian civil war as it unfolded.

GAZETTE: During the three waves of interviews, how many people did your team survey?

MIRONOVA: We did quantitative research, which consisted of [interviews with] about 50 Islamic fighters, mostly originating from the Islamic Front, 100 FSA soldiers, 200 ex-fighters, and 100 Syrian civilians. I also conducted qualitative interviews with media activists, medics, fighters from minority groups, [and] humanitarian workers to have a broader picture of the situation.

GAZETTE: How did you go about communicating with these groups of people?

MIRONOVA: We had trained specialists on the ground in Syria. Our specialists spoke [in] fluent Syrian Arabic. They were trained both in ethics for IRB [Institutional Review Board] purposes and [in] how to conduct interviews. In terms of getting permission, we used our connections to reach out directly to the top command. For example, to interview Islamic militants, we received permission from ISIS religious courts. We did everything above-board to prevent endangering our surveyors.

GAZETTE: Did your team encounter any resistance to being interviewed?

MIRONOVA: Surprisingly, it’s not that hard to find participants. Mostly because the fighters, especially Islamists, expect to die tomorrow. They have no expectation for the future, so the present is expendable. They’re all very honest because they just don’t care about the consequences of speaking truthfully. Also, since we asked only personal opinion and experience questions, participants were less suspicious.

GAZETTE: Regarding the ongoing conflict, did you notice a philosophical difference in approach between the groups you interviewed?

MIRONOVA: Conflict termination was one area where groups vastly differed in opinion. For the militants, Islam is the art of war for decisive military victory. They are not willing to negotiate and wouldn’t even entertain the opportunity to sit down and discuss terms. The FSA, on the other hand, are much more open to talks — even concessions. For Syrian civilians, especially refugees, they are just looking for a conclusion. They would more or less say, “We don’t care any more. You want to negotiate? Yes, perfect.” There’s a huge divide between militarized rebels and civilians.

GAZETTE: It’s anyone’s guess how all of this will end, but it seems likely that any chance of a peaceful settlement requires opposition groups finding a way to coexist. Were you able to get a sense of the sociological fallout — how each group would respond to one another, should the current government reach a compromise or be overthrown?

MIRONOVA: One thing we asked groups [was] their opinions on the Alawite people in regard to their support of the Bashar Assad regime. We posed the question of whether they could live with them after the conflict — in the same house, work in the same space, and so on. Surprisingly, the majority of people responded positively. It summed up to “we have lived during the war — we can live after the war.” I think they understand that it could not go on forever like that.

GAZETTE: You also mentioned that you conducted qualitative interviews during your time there. Was there anything you discovered from speaking on a one-on-one basis that wasn’t covered in the survey data?

MIRONOVA: The most surprising result was that fighters chose Islamist groups, not only because they care about Islam, but because those groups are the most organized and are better trained. They provide more benefits, leaders fight side by side with the soldiers they command on the front line, and most important of all, they take care of their wounded fighters. Everyone in the media emphasizes religion as the driving force, but that’s not the case for all that join.

Also, with the war being a total mess, families are sending one son to fight with the FSA and another one with ISIS/al-Qaida, just in case. Families did the same thing during WWII in Yugoslavia. People care about ideology less and less — they are just looking for ways to survive.

To view the complete pdf “Voices of Syria” project, you may download it here. In addition to Mironova, Loubna Mrie of Syria and Sam Whitt of High Point University also contributed to the project.

This article was originally published in the Harvard Gazette on April 8, 2015.